By the time I created the Enola Holmes mystery series, I had plenty of experience. After discarding the usual number of failures and successfully publishing 40 novels, I learned over and over again that, for fiction, my prose needed to be all about pictures.

The root word of “imagination” is “image.” My cockeyed job as a novelist is to envision scenes in my head, then write—just black words on white paper—in such a way as to enable the reader to envision the same scenes in their own head in living color. I engaged in a sort of crypto-telepathy, writing mostly from my daydreams (fantasy) and real life (contemporary fiction).

Sometime around 2001, an editor asked me to follow up a different series with something “set in deepest darkest London at the time of Jack the Ripper.” I was baffled, until I realized that Sherlock Holmes had lived—fictitiously—at that time. Enola Holmes! I knew her name instantly. And I soon knew she was going to be Sherlock’s kid sister and his competition—in a quaintly feminist way.

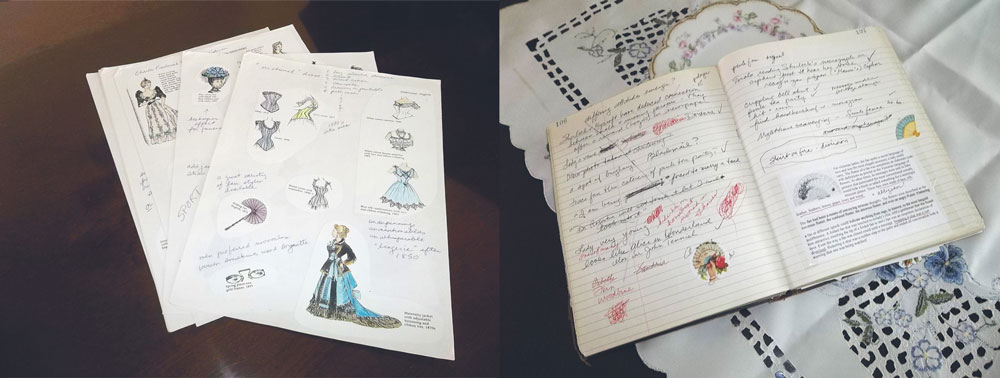

I had that feeling—a sort of singing sensation in the mind—that it would be a hit. But I had never written a historical novel, so I plunged into reference books and online searches. I knew from experience that, when writing, it works to play; there’s nothing like child’s play to internalize data. So, I photocopied line drawings from a costume book, colored them, and stuck them to my office walls; I found a battered leather journal and filled it, almost as if scrapbooking, with notes, pictures, and stickers. If I can take any tenuous credit at all for Enola Holmes having been made into a movie, it would be due to my technicolor approach to writing it.

In her research for the Enola Holmes Series, Nancy Springer was driven by images, which she sketched, colored, and pasted on paper.

In her research for the Enola Holmes Series, Nancy Springer was driven by images, which she sketched, colored, and pasted on paper.

Enola turned out to be a tree-climbing tomgirl with the stork-like build and looks of her more-famous brother. Rather than be sent to finishing school, she runs away, using the corset, bustle, and bosom enhancer that were forced upon her to store all sorts of supplies and disguises. While eluding her brothers, she also searches for her missing mother and solves mysteries along the way. She can run rings around Sherlock because he does not understand the secret codes of Victorian women undermining the men who try to control their lives. And she does all this at 14 years old.

Once Enola had been brought to life on the page, she captured readers’ imaginations like she had captured mine. One such reader was the youthful actor Millie Bobby Brown of Stranger Things, who decided she wanted to make a movie based upon them. She spearheaded the entire project, becoming Hollywood’s youngest producer.

When I was consulted on the first script, I took it very seriously and suggested thoughtful changes. But when I saw a later script, it bore hardly any resemblance to the first one, and even later versions had morphed almost beyond recognition! It was not until the summer of 2019, when I traveled to England to visit the set, that I understood and appreciated the process of filming as a fluid and organic confluence of many creative minds.

But mostly I observed with excitement and awe as hundreds of people worked together to transform my image-based story into the kind of picture I could only have imagined: a motion picture. Seeing the movie for the first time felt surreal, as if I had fallen into one of my own daydreams. I am still blinking in disbelief.

by Nancy Springer ’70

Photos courtesy of Nancy Springer and Netflix

Posted: 05/03/21