The definition of creativity is somewhat nebulous and absolutely individual. It can be found at the root of how a mathematician approaches an equation, how an educator connects to students, and how a poet develops a stanza. Yet, ask a writer, painter, fashion designer, or musician with ties to Gettysburg College, “What is creativity?” The answer: it is a process, a passion, and a revealing of one’s self.

Whether studying physics or fine art, a Gettysburg College education serves to test and refine creativity— encouraging students to not only ask sharp questions, but also to develop understanding through exploration, experimentation, critical thinking, and compassion. These skills pay dividends today, at a time when developing new ideas, inspiring quality work, and making meaning through unexpected connections—all elements of creativity—are increasingly seen as requirements for success in a variety of fields, not just those traditionally marked as creative careers.

Dick Boak ’72, an illustrator, author, woodworker, luthier, musician, and retired archivist for Martin Guitar, has always been a man of many interests. “People tend to isolate creativity into mediums—music versus painting, for example. I was interested in all of them,” he said. “Each medium is like applying a little bit of mercury on a mirror. They all meld together to reveal an approach to how you do a task. The approach is the art.”

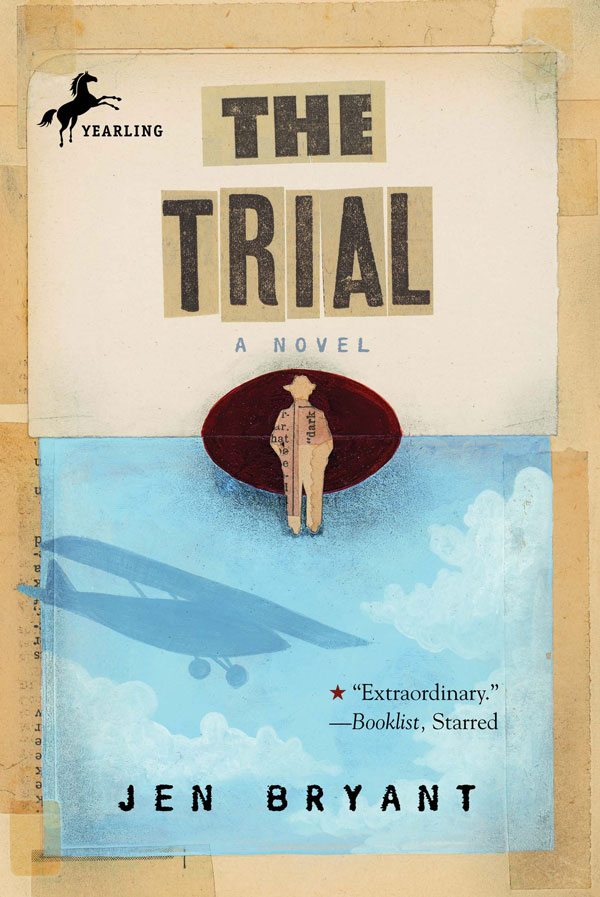

“In my office, there are files with labels distinguishing a first draft of a novel from the editorial correspondence or the research for that novel. In reality, all of my files are connected,” she explained. “A liberal arts education is like that: you might take a biology course and a creative writing course in different departments, but the reality is that you’ll integrate, cross-reference, and cross-pollinate the knowledge and experiences in those courses for the rest of your life. It’s an education that’s deeper and so much richer in creative potential than a hyper-specialized one.”

For Bryant, in-depth research is key to following through on projects, but her ideas always begin with an emotional response. For instance, when she learned the notes of “Quartet for the End of Time” were inspired by birdsong Messiaen heard while he was in a World War II prison camp, Bryant knew she felt a strong enough emotional connection to Messiaen’s story to write his biography. “Writers differ in how they begin, but more often than not, it feels like my subjects choose me, rather than the other way around,” said Bryant.

It feels like my subjects choose me, rather than the other way around.”

Inspiration can flourish in this steeping process, when tendrils of knowledge seem to inexplicably intertwine. While students examine masterpieces in the classroom, their exploration outside of the classroom is percolating in the background, and vice versa. Whether it is witnessing the vibrant colors of Morocco or listening to the laughter of a child playing in Nicaragua, the sights and sounds of the world add life to art.

Kressley, who is working on a new show for the television network Bravo called Get a Room with Carson & Thom, compares cultivating creativity to the work of our taste buds and muscles. “Like taste buds, everyone’s creative process is unique, developed through ideas, experiences, and sensibility. You also have the ability to flex your creative muscles by going outside of your comfort zone, as I have had to do in my new show where I am exploring interior design for the first time.”

The College’s programs, including its robust global study offerings, provide students the important opportunity to explore and flex their creative muscles. Inayah Sherry ’19, president of the International Club, reflected on how these experiences influenced her creativity. An international student from Barbados, she studied in the South of France and completed a summer fellowship in Nepal through the Center for Public Service.

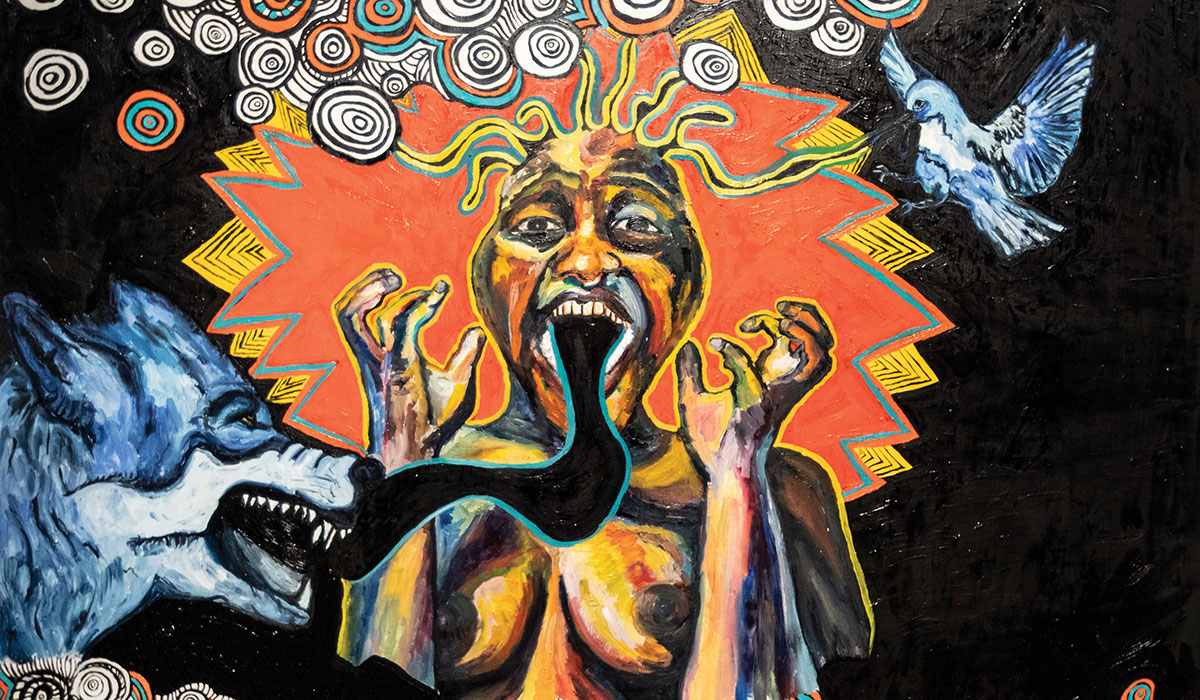

“Traveling abroad allowed me to see myself in a global context and experience different interactions around the world, which plays into my art and how it has developed while at Gettysburg,” she said. Sherry, a studio art major with a concentration in psychology, intends to use her combined academic background to pursue a graduate degree in art therapy this fall. Sherry’s academic combination is one of many that cross-pollinate disciplines, melding the creative and artistic arenas with the mathematical and scientific.

The uniqueness of each person’s creative process is born, not only from their tastes and experiences, but also from the ability to suppress outside influence. Rigidness and closed-mindedness— succumbing to the way things have always been—have no place in the creative process.

Tullio DeSantis ’71, a contemporary artist, writer, technologist, and teacher, sees having the ability to remove preconceived notions and stigmas as an essential element of the creative process. The individuality and uniqueness required to create something new comes from our personal identities rather than a cultural identity, he explained.

DeSantis and Boak met while students at Gettysburg College. DeSantis was a year ahead of Boak, acting as his “carrot on a stick.” After graduation, the two kept in touch, continuing to admire one another’s work, which led to the opening of a joint art exhibit in New York City in November of 2018 entitled “Illustrations and Guitars by Dick Boak and Paintings by Tullio DeSantis.”

“To create is to bring forth something entirely new,” said DeSantis. “This is possible only if one is able to separate oneself from the culture at large long enough to see or say or make something truly original.” In other words, you need to be able to push yourself beyond the confines of your own experience and thinking.

Separating one’s personal and cultural identities, as DeSantis suggests, requires a great deal of introspection and vulnerability. Ari Isaacman-Beck, an accomplished solo violinist and visiting assistant professor at the Sunderman Conservatory of Music at Gettysburg College, believes part of his job is to create an environment in which students are able to be vulnerable and connect to music emotionally. To do this, he focuses on limiting his students’ self-criticism by framing his feedback around how they play, and not how he would play, a piece. From there, he helps them develop their own interpretations.

“Knowing the emotional narrative of your interpretation of the music is something we need to do to have any chance of relating to the audience. It can be uncomfortable to experience such emotions and then share them with an audience,” said Isaacman-Beck. “That vulnerability and openness to the audience is what has always drawn me to the arts. That is what gives me chills.”

Isaacman-Beck explained that the creative process not only requires freedom, dedication, and logic, but also a great deal of vulnerability — both in the process and performance. People must allow themselves to be self-reflective, introspective, and even frustrated at times. For students and artists alike, “there is a fine balance between the drive to produce and the suppleness needed to be kind to oneself,” he said. Though sometimes delicate in an academic atmosphere, Isaacman-Beck strives to create that environment at the Sunderman Conservatory.

Isaacman-Beck explained that the creative process not only requires freedom, dedication, and logic, but also a great deal of vulnerability — both in the process and performance. People must allow themselves to be self-reflective, introspective, and even frustrated at times. For students and artists alike, “there is a fine balance between the drive to produce and the suppleness needed to be kind to oneself,” he said. Though sometimes delicate in an academic atmosphere, Isaacman-Beck strives to create that environment at the Sunderman Conservatory.

Gettysburg professors past and present have played a key role in cultivating the creativity of their students, no matter how nebulous a process it may seem.

For Boak, it was Art Prof. Norm Annis, who passed away last year, who inspired him to pursue a life of art.

For Inayah Sherry, it was former Gettysburg Prof. Amer Kobaslija. “Throughout my entire Gettysburg experience, he was a mentor to me,” said Sherry. “He not only encouraged me to create, but I was also drawn to the way he viewed the world and his absolute passion for the artistic process.”

Bryant also reflected on her time as a Gettysburg student — a chance for inspiration and self-exploration. “In order to create something new and authentic, you have to know who you are. Before I came to Gettysburg, I knew who I was supposed to be, but not really who I was. The school offered then — and still offers now — a place where self-knowledge and self-discovery can happen,” she said.

It can be uncomfortable to experience such emotions and then share them with an audience.”

In self-discovery, any student, any person, would likely find the existence of an inner artist. “A person is an artist if they are doing art,” Boak explained. “You are what you are doing at any given time. I like that people allocate their time to creativity. That in itself has intrinsic worth.”

No matter the field of study, creativity is an essential process that takes a lifetime of refining, flexing, and discovery. It is an act of passion and persistence. It is a centerpiece of the Gettysburg education. As Kressley put it, “Whether problem solving is societal, scientific, or artistic, open-mindedness, critical thinking, and creativity go hand in hand.”

By Devan White ’11

Posted: 06/05/19