Gettysburg College’s history is intertwined with that of the Civil War and the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, during which Pennsylvania Hall served as a field hospital. The Gettysburg National Military Park sits just steps from campus and paints a picture for one of the greatest turning points in history. However, that is just one narrative for both the nation’s history and for the College.

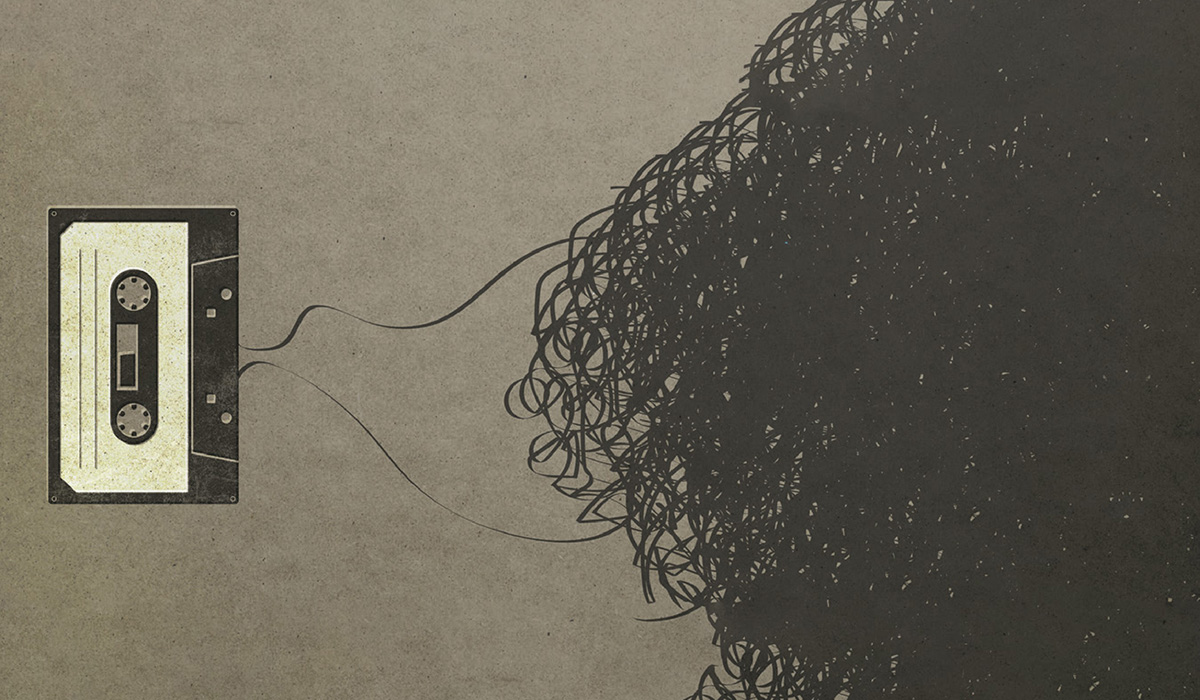

“There’s a concept that we use as historians and archivists called institutional memory,” said Musselman Library Archives Assistant Devin McKinney, who oversees the College’s oral history collection. “It refers to the living memory of an institution—in this case, Gettysburg College—and it exists in the minds of everyone who’s been through here in one way or another, as a student, staff, or faculty member.”

“How do you save those moments in time?” McKinney continued.

“You ask people to talk to you. Get it down on a recorder and into a transcript, and eventually you have an enormous repository— an infinity of stories told by the people who have made this place. That’s institutional memory. It’s the story of Gettysburg College.”

Oral history is just one way to document our past to honor it and learn from it. As times evolve, what is documented and then taught shapes each generation’s perceptions of history. To supplement the facts found in textbooks, primary sources help complete the picture, as some lived experiences differ from documented experiences.

“Memory is important,” said McKinney, who is currently addressing gaps in the College’s collection by seeking and adding the voices of African American and LGBTQIA+ staff and alumni. “The past has to be kept alive.”

From conducting oral histories and hosting engaging classroom discussions to archaeological excavations and critical examinations of Hollywood cinema, members of the Gettysburg College community share how they continue to discover new ways to preserve memories throughout history.

KURT ANDRESEN

Ronald J. Smith Professor of Applied Physics, Physics Department communications lead

In physics, like any discipline, we tell stories—stories about amazing discoveries, stories about scientists persevering in the face of adversity, and stories about people getting things amazingly wrong. However, we found, like many disciplines, that despite being an incredibly diverse field with scientists from all backgrounds, countries, and gender identities, our stories were predominantly about white men.

In an attempt to expand the range of characters in our stories to more accurately reflect how modern physics is done, we joined the Scientist Spotlights Initiative. This initiative utilizes, among others, students and faculty to research and provide stories that may be missing from our textbooks. Spearheaded by Physics Chair Bret Crawford and former Visiting Prof. Ya-Wen Chuang, the Physics Department faculty and students went about researching stories about people like Lise Meitner, Marie Curie, and Jagadish Chandra Bose.

When the department first started doing this, the Scientist Spotlights Initiative did not even have a section for physics. We had to contact the Initiative to get them to add this category. Now, there are more than 50 scientists in the physics category—and Gettysburg College students and faculty continue to add to these every year. These stories are read as part of our classes throughout the Physics Department courses.

While there is a lot of work to do to continue to tell the hidden stories of physics, this is a small step in the right direction that we are happy to have been able to make.

MICHAEL J. BIRKNER ’72, P’10

Professor of history

The emergence of scholarly history in the late 19th century was accompanied by what I would describe as “the cult of the document.” For generations, research for dissertations and published histories rarely deviated from an exclusive reliance on correspondence in private hands or archives, supplemented by printed materials. A turning point in research on modern history topics occurred shortly after World War II. Cognizant that in the age of the telephone and increasing mobility, candid, detailed correspondence was diminishing, historian Allan Nevins argued it was time to add a new dimension: oral history interviews, recorded and transcribed.

Nevins’ work establishing an oral history program at Columbia University inspired projects at presidential libraries and various universities. At Gettysburg College, initial steps in collecting interviews commenced in the 1970s in several January Term courses taught by English Prof. Jack Locher GP’23 and one interview with a college elder by History Prof. Charles H. Glatfelter ’46.

When I arrived in 1989 to teach 20th-Century U.S. History, the potential for oral history as a teaching tool and archival collection seemed obvious. I began assigning oral history projects to the Historical Methods course and courses focused on U.S. history since World War II. Over the past 35 years, the College’s collection has grown to more than 1,800 oral histories, roughly half of them relating to World War II. Other projects have examined individual presidential administrations since that of Gen. Willard S. Paul, the Lincoln Highway, “Making a Life,” Vietnam veterans, and African American students’ lives at the College. One ongoing project explores the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic at Gettysburg College.

The World War II interviews have also provided the foundation for two books published by Musselman Library:“Common Cause,” which I co-edited with Archives Assistant Devin McKinney, and “Democracy’s Shield,” which I edited in collaboration with two students, Grace Gallagher ’22 and Rachel Main ’22.

It can fairly be said that Gettysburg College’s oral history collection is one of the most extensive—if not the most extensive—among liberal arts colleges in the U.S.

CHELSEA BUCKLIN ’10

Archives specialist, Library of Congress

As the collections manager for the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, I am responsible for the physical preservation and security of our unique and irreplaceable collections. This includes managing our stacks both on Capitol Hill and at our state-of-the-art off-site storage facilities, picking up new collections, coordinating conservation treatments, ordering preservation housing supplies, and, in my spare time, processing collections.

It is my privilege to help preserve the written record of the American experience—the highlights and lowlights alike. History is often a narrative collectively agreed upon to help make sense of our past, who we are, and where we came from. As time and people evolve, that narrative can be altered to support individual ideologies straying from the truth. Preserving the accounts of what actually occurred through the correspondence, reports, photographs, and more is imperative to ensuring future generations understand the realities of the past—not only to learn from mistakes, but also to celebrate successes and take those forward into a brighter future.

In this day and age, we also suffer from an over-inundation of information. It can be incredibly difficult to wade through the sea of extraneous emails, social media posts, and cat pictures to get to the information we seek. Archivists and librarians are essential in this information age. It is our role in society to filter out the noise, preserve, arrange, and describe collections, ensuring discovery in a timely and accurate manner. Knowing the work that I do facilitates the work of historians, scientists, journalists, artists, and students alike is very fulfilling.

BETH DESROSIERS M’23

Arrowhead Union High School AP U.S. History teacher, Gettysburg College-GLI master’s graduate

History is about stories. Storytelling sparks students’ interest. Dates and names are difficult to remember, but an intriguing story is memorable.

When I set out to research antebellum Oberlin, Ohio, as part of my capstone project for the Gettysburg College Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (GLI) Master of Arts in American History program, I thought I would focus on Oberlin College’s early acceptance of female students. Instead, I discovered a story even more compelling—the story of Oberlin’s involvement in the Underground Railroad, culminating in the adventure and subsequent trial that became known as the Oberlin-Wellington rescue. This was a story of an entire community rallying to rescue a fugitive from slavery.

One of the most fascinating primary sources I encountered in my research on antebellum Oberlin was an 1850 petition by members of the Black community living in Oberlin to retain the president of the college, Asa Mahan. Eighty-seven “colored citizens” of Oberlin signed the petition imploring Mahan not to resign. Oberlin’s founders hoped to create a utopian religious community during the 1830s. They succeeded and developed into a community whose actions spoke louder than words. Black students were allowed to enroll, and a thriving free Black community was welcomed and supported.

The current debate about critical race theory has attempted to apply political influence to what is taught in the classroom. No history teacher I know tells students what to think. Instead, we hope to inspire students to think for themselves. As a history teacher, I have a responsibility to tell the sad stories alongside the optimistic stories. The story of Oberlin’s community was such a hopeful story, one in which a thriving free Black community challenged the founders of Oberlin College to live up to their ideals. The result was a symbiotic relationship between the college and the Black community, which in turn led to direct action against slavery.

MATTHEW JAMESON ’12

Ph.D., Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology, Bryn Mawr College; Regional principal investigator, Chronicle Heritage Arabia Traditionally, historical narratives were constructed from the top down with a focus on imperial interests and global events at the expense of the lived experience of everyday communities and the non-elite. Such teleological approaches offered an easy way to quickly synthesize thousands of years of human history to broad audiences. The picture, however, is never so simple.

I became an archaeologist because of my desire to explore our human history from a different perspective. Archaeology is the study of past groups and peoples through the analysis of material and physical remains. It can be carried out at different scales of investigation from reconstructing the diet of an individual to recognizing shared beliefs and practices across an entire region. What drew me to archaeology was its potential to shift our notions of history from the ground up through the excavation, recovery, and study of the past.

My research today focuses on the Arabian Peninsula, where Chronicle Heritage is currently engaged in several projects in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The stories we have told about the inhospitable Arabian Peninsula for centuries, perhaps essentialized in the film “Lawrence of Arabia,” are slowly being deconstructed by our ongoing fieldwork. The archaeological work that we are conducting in central and northwestern Arabia is revealing a complex landscape with evidence of human occupation from the Paleolithic Period to the Modern Period. During these 200,000 years of human history, communities adapted local strategies—including the domestication of the dromedary camel and the development of oasis agriculture—to meet their needs that were divergent from the neighboring regions of Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The stories we tell about the past matter because they can help us to understand the multifaceted lifeways of our modern world. Archaeology provides an avenue to give a voice to the voiceless past and thus tell a different kind of story.

CONNECTING HISTORY AND CULTURE THROUGH MUSIC

by Corey Jewart

Like words in a book or images on a tapestry, music plays an important role in how we share stories throughout human history. With the right combination of sounds, a musician can elicit emotional responses from listeners that transcend the here and now, allowing them to immerse themselves in the past and gather context for the future.

In late March, during a three-day residency in Gettysburg, renowned blues musician Corey Harris shared his personal history and that of his ancestors and the musicians who came before him. As he strummed his fingers across his guitar, he carried with each chord a message from the past—one he hoped would give people a greater understanding of the complexities of our world and the many ways we can work together to improve it. His artistry extended beyond traditional blues, incorporating reggae, soul, rock, and West African influences, to showcase an interconnectedness of history and culture.

As part of the programming supported by the Ann McIlhenny Harward Interdisciplinary Fund for Culture and Music, Harris visited seven Gettysburg College classes in the History, Africana Studies, Music, Peace and Justice Studies, and Art History Departments. Students and faculty listened attentively as Harris’ words and compositions provided enlightenment about our global society.

Harris, a 2007 MacArthur Fellowship recipient, also conducted two guitar workshops to share his knowledge and passion with future musical storytellers, and performed locally at SpiriTrust nursing home and Vida Charter School. On his final night, Harris played for more than 600 community members at a free public concert at the Majestic Theater. His set list included songs of freedom and enslavement, of belonging and segregation, and of love and despair.

“Corey Harris’ presence on our campus was transformative,” said Michael Pires ’27. “His soulful music and thought-provoking lyrics really resonated with us all. His performances sparked conversations about culture, history, and social justice.”

KATIE LAURIELLO ’25

Traveling to England was an experience I’ll never forget, especially the three-week London seminar with Art and Art History Prof. Felicia Marlene Else, Curating London: Using Objects to Tell New Stories. … [It] asked us about our own biases reflected in the museums we look to for learning— the places where we go to field trips as elementary schoolers to learn more about the world around us. As children, we may not have realized that the very people who create these museums, as institutions of learning and collections of histories, are not free from bias and that the provenance of the objects displayed is often a story left untold or even deliberately concealed.

Prof. Else put us in a dialogue with each museum, asking how they are going to do better than their predecessors to reunite objects with their ancestors and cultures through repatriation. Such a dialogue could be no further demonstrated than our group presentations in the British Museum, the poster child of colonization and the figurehead of repatriation, in which institutions like museums are asked to return objects to their original owners. There, we analyzed objects on the “Collecting and Empire Trail” and other contested objects, such as the Elgin Marbles, Rosetta Stone, and the Benin Bronzes. Throughout the seminar, we noticed that the information gaps shared in the museums compared to their websites are wide and highlight our public perception of museums, history, and art. … This information gap emphasizes how valuable our ability and motivation to search for the truth really is.

… [Prof. Else] challenged us to think critically about the way museums and similar institutions of education present their stories and information. She brought an infectious amount of liveliness and joy into each classroom lecture and museum visit.

JING LI

Professor of Asian Studies

I am a folklorist from China, and I vividly recall the pivotal moment when I had to decide on a major for my graduate studies. After growing weary of poring over grand, abstract literary theories, the field of “folklore” seemed incredibly intriguing to me, thinking that I could finally study the real lives of people and their worlds. I am glad that I did choose folklore, even though I must admit, at that time, the concept of “folklore” remained somewhat elusive to me.

Over the years, being a folklorist has enabled me to take my students on a different journey when it comes to understanding China, whether exploring the metamorphoses of folktales, the historical transformations of beliefs and rituals, or the changing customs in everyday life like foodways, festivals, and travel practices.

In one of my courses, Travel Writing, Tourism, and Culture in China, I tasked my students with delving into travel accounts penned by Westerners from different historical periods. The aim was to juxtapose these narratives with the students’ own research on China’s history gleaned from textbooks. The results were eyeopening for the students, as they “re-lived” the lives of ordinary Chinese in each period as well as encountered vastly different portrayals of China, even from the same historical periods. China ceased to be a twodimensional map but became a multifaceted Rubik’s Cube puzzle, with countless sides that students needed to decipher, understanding the “moves” that shape the composition of each side.

I often tell my students that they may quickly forget specific information they have learned in the classroom. But one thing I hope they take with them is that to understand a culture means understanding its people and their ordinary lives. To comprehend its history is to grasp their lived experiences, expressions, memories, and voices that may not always find their way into the pages of historical documents.

SALMA MONANI

Chair of Environmental Studies

Since the early 20th century, much of Hollywood cinema has shaped the world’s sense of American history, including that of Native peoples in this history. Many of us are familiar with the genre of the Western, and perhaps even familiar with its origins in the Wild West shows of the 1870s that celebrated the nation’s Westward Expansion and possession of Native lands. In the mid-20th century, more than a quarter of Hollywood’s output involved Westerns that demonized Native peoples as the enemy on the frontier. With the 1960s, a “revisionist” Western more sympathetic in its Native portrayals evolved. However, rarely have Native people had creative control over these portrayals, and Hollywood stories skew toward stereotypes like the “ecological Indian”—a noble yet primitive person living an anachronistic pre-modern existence. As a science-fiction fantasy of humans seeking new space frontiers, James Cameron’s “Avatar” franchise is a good example of a “revisionist” Western.

Recently, Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” (2023) received praise for doing better with its Native representations. Recounting the history of Osage murders in the 1920s when oil was discovered on reservation lands, Scorsese actively consulted with the Osage community, and he begins to fill a gap in how Hollywood documents Native histories. It’s not alone, as television shows written, directed, and performed by Native peoples, like the critically acclaimed episodic comedy-drama “Reservation Dogs” (2021-2023) and the crime thriller “Dark Winds” (2022-) are also complicating simplistic renditions of Native life on screen.

Native creatives bring experiences from working with their communities and within less visible Indigenous networks of cinema and media production to bear on these more mainstream productions. My research examines what we can learn about cinema by considering Indigenous participation. My forthcoming book, “Indigenous Ecocinema,” is particularly interested in how cinema made by Indigenous peoples expands our sense of cinema’s environmental practices and theories of ecomedia.

by Megan Miller

Posted: 07/02/24