On November 24, 1963, Richard Hutch ’67 and his classmates boarded a bus to Washington, D.C., to pay their respects to the late President John F. Kennedy. During tumultuous times, the College’s seemingly simple act of organizing a bus trip to D.C. fueled Hutch’s desire to add value to the world.

When “goodness was struck down [and the president was assassinated], some students started to change the conversation on campus,” he reflected in 2015, during a campus presentation for a symposium on the American civil rights movement.

“In a matter-of-fact way, Gettysburg College helped me get into the wider world of what it meant to be an American,” Hutch said. “Just by getting on that bus, I was on my way.”

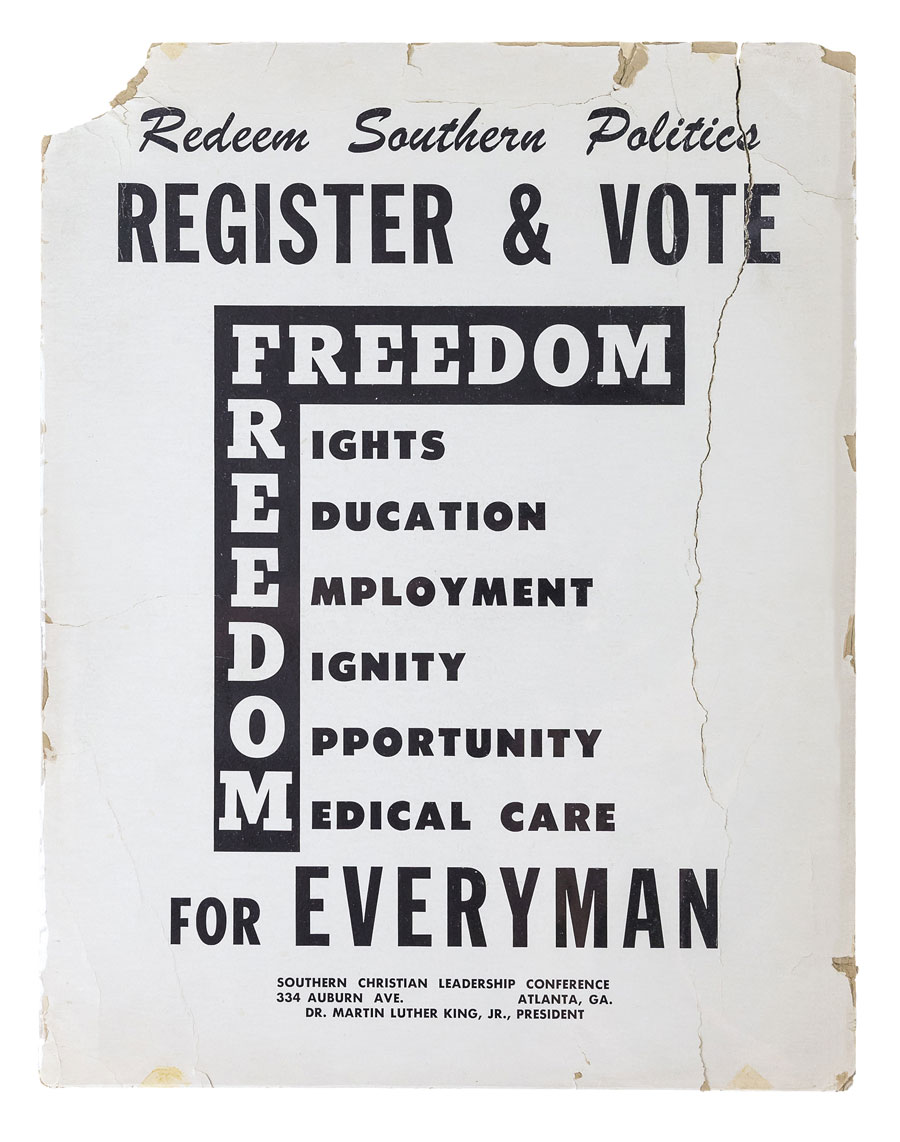

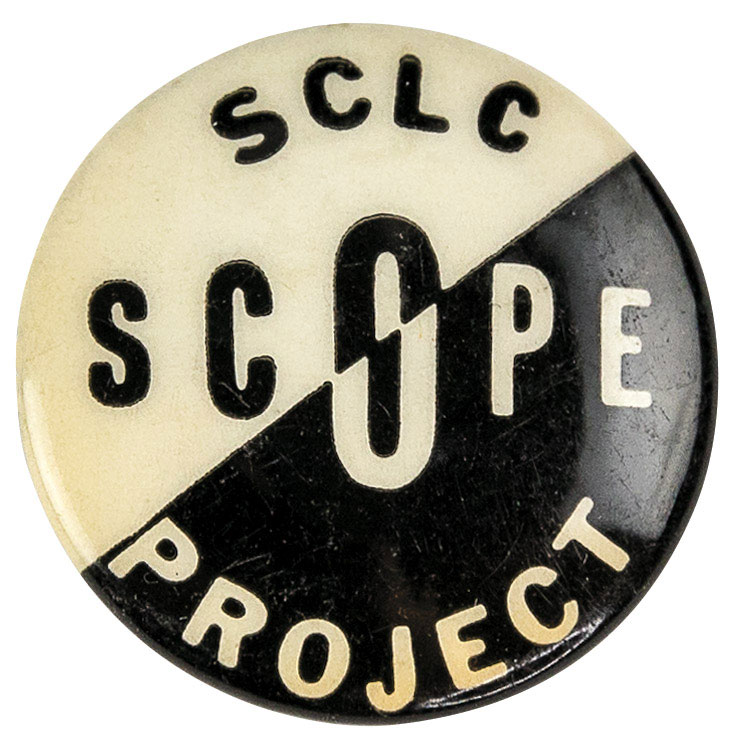

Two years later, a rally cry reverberated throughout the nation after the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson in Selma, Alabama. Gettysburg College’s Chapel Council, then known as a “beacon of light” for social commitment, according to Hutch, brought a group of recruiters from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to Gettysburg to speak about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights movement in the Deep South.

“Then and there, I decided I must go south,” Hutch said. “My conscience permitted no other choice.”

The famed protest song “We Shall Overcome” had taken hold in Hutch, as yet another bus was organized by Rev. Dr. John Vannorsdall ’72 to Atlanta. There, Hutch and fellow classmates joined students from other colleges and universities to receive nonviolent activism training before their deployment to an Alabama county. Their intention was to encourage black individuals to register to vote at the courthouse. Hutch took beatings and shotgun pellets to the leg, yet—inspired by the history of his College in the north, including Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address that took place 100 years before his first year at Gettysburg—he knew there was no turning back on “all that yet needed to be done.”

“This was my duty,” he recalled.

On the day Hutch returned home, August 6, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

“Coming back to Gettysburg and the entire Gettysburg community, I was beginning to try to envisage King’s beloved community in an ever-expanding mode,” Hutch said. “The summer of 1965 changed my life in profound ways, as fate pulled me further into the future.”

Shifting perspectives

During his installation ceremony on September 28, 2019, Gettysburg College President Bob Iuliano spoke of King’s observation that “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

Here, Gettysburgians, past and present, enter a path shaped by civic engagement, one that can strengthen that garment. They strive to make a difference across the globe, becoming leaders of action and integrity, looking to examples set by those such as Lincoln and President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

But those moments of action prove unique to each student who steps foot on campus.

When Leon “Buddy” Glover ’71 entered the College in 1967, there were few students of color, he remembered. In fact, he was the lone person of color to graduate from his 500-member class and only the 12th overall in the College’s history. The first was Rudolph Featherstone ’56.

“There just didn’t seem to be a conscious pattern to make it any different,” Glover told archives assistant Devin McKinney, during a campus visit in 2015 for Musselman Library’s oral history collection.

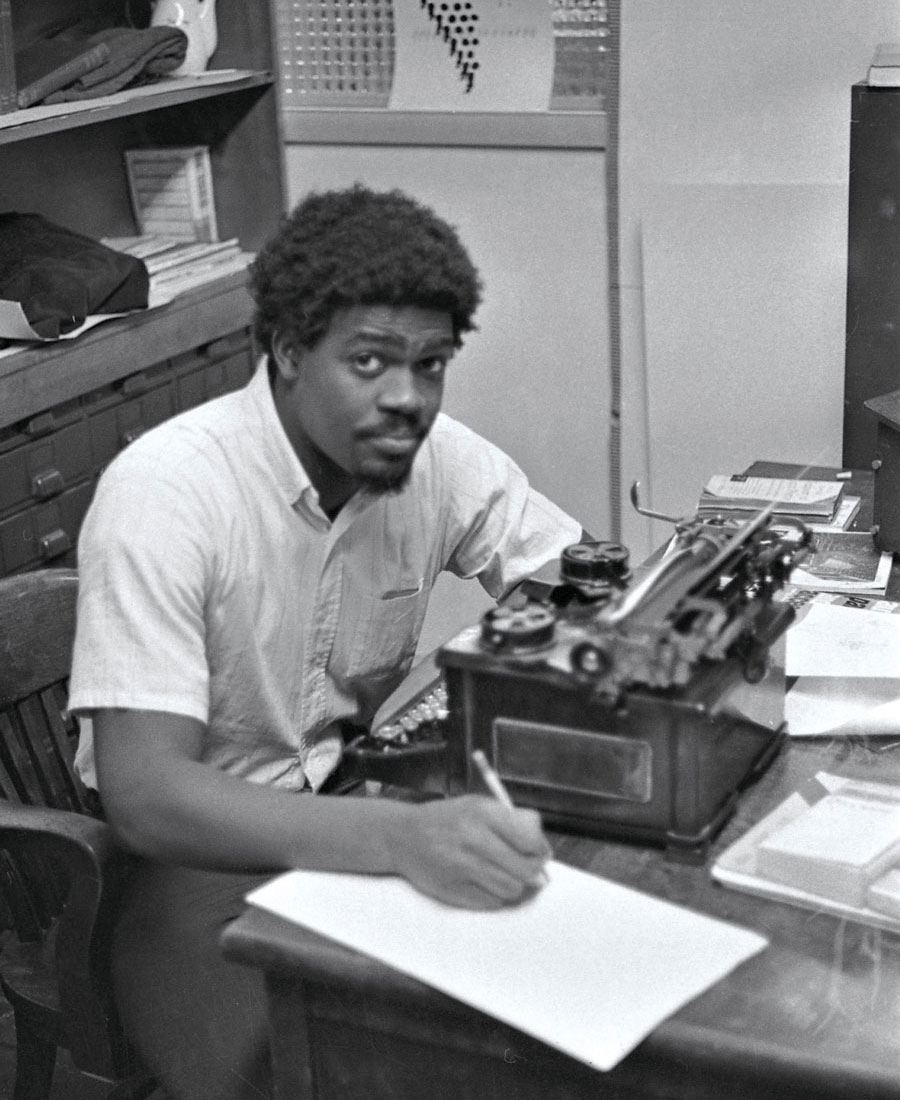

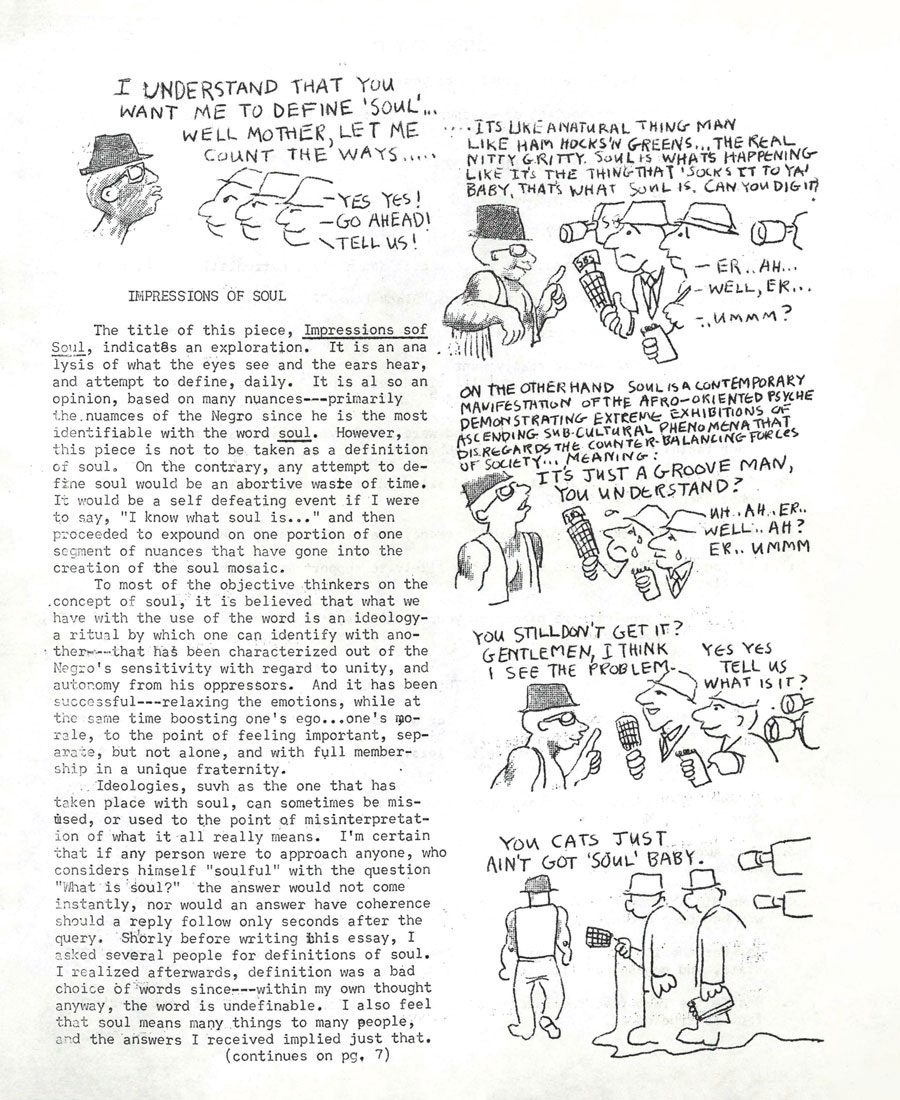

So, Glover launched a newsletter called “Black Awareness,” for which he wrote a majority of its content as the editor. Inspired by King and the Malcolm X Black Hand Society of the World, he summarized racial issues in his introductory column, noting: “Blacks can no longer send whites anywhere to speak for them. We must step forward and speak for ourselves.”

“Sometimes you’ve got to come at it hard in order to get people to listen—even the administration,” said Glover.

“I will never forget the first day when this newsletter came out and the impact that it sent across the campus,” added Glover, who became Lancaster County’s first black principal in 1987. “We only ever [published] two issues—that was enough.”

As society evolves, so does the College’s responsibility to engage with it.

“Over time, the definition of civic engagement has changed,” said Ivana Lopez-Espinosa ’19, who was the first student worker in the College’s Diversity & Inclusion Office and is now pursuing a master’s degree in higher education with a concentration on diversity and social justice. “In the ’70s, the College had the Knoxville Exchange, [an immersion trip to Knoxville College to encourage students to engage in interracial dialogue]. The Center for Public Service has been around since the ’90s. Students have been vocal about their needs, so activism has been present. I think it grows and is redefined as society progresses.”

Early Lutheran presidents of the College, then known as Pennsylvania College, were committed to “raising young people to give back to society, to strengthen society,” said Josh Stewart ’11, who, after six years with the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, currently works for Fahe, a nonprofit devoted to ending poverty in Appalachia.

In 1933, one of the first two women who graduated from the College, Margaret Himes Seebach, Class of 1894, known for being a pioneer for the College in many ways, organized 200 alumnae from 20 states to sign a petition to make Gettysburg fully coeducational.

“Not all of us are frontline activists, but you do it in your own way. It’s because of this belief. It’s in our culture,” said Jean LeGros ’73, associate vice president emerita of alumni relations at the College—and the first to hold that position—who researched the admission of women to the College. “Care and advocacy for others were part of [Seebach’s] making. … Gettysburg College is a wonderful place to foster that.”

“It’s our obligation to go out into the world both as students and alumni and carry that forward,” LeGros continued. “We’re much better as people when we look outward, rather than inward.”

From protests of the Vietnam War in 1970, to the Student Senate addressing issues in support of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community in 1991, to campus-wide discussions on climate change in 2019, the issues may change over time, but Gettysburgians remain engaged on issues that matter.

“Civic engagement is not just big-world questions, but it’s also what’s happening in your community,” said Marc Fialkoff ’10, a regulatory specialist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, who serves as a global expert on nuclear transport laws and security for the International Atomic Energy Agency. “Civic engagement is scalable, from issues of the College to helping countries in Central Asia and around the world transport nuclear and other radioactive materials securely. Gettysburg, in that sense, provides a microcosm of how to engage.”

In Lopez-Espinosa’s second year with the Office of Diversity & Inclusion, she created a timeline of “firsts” to document accomplishments of underrepresented students at the College. As she researched, Lopez-Espinosa described herself becoming more aware of the conversations Gettysburg College had around diversity. As a first-generation student and an immigrant Mexican woman who joined her parents at weekly English classes through the Center for Public Service, she initially thought the odds were against her. She vowed to be receptive of new experiences, asking questions and conversing with others to welcome reflection.

“Once I understood the power I held as a student representative with a direct link to the administration, it was important that I foster relationships with students to understand the changes they sought,” said Lopez-Espinosa, who also served as vice president for the Latin American Student Association and as secretary for the Muslim Student Alliance during her senior year. “I knew that my experiences weren’t reflective of the student population. If I wanted to improve the experiences of students, I couldn't base it on my own thoughts.”

When Phoebe Doscher ’22 arrived on campus in the fall of 2018, she witnessed “a change-making energy” to transform ideas into action. Political clubs encouraged everyone to register to vote, others connected with the library to shed light on soaring textbook prices, and most recently, a student petition circulated to increase student wages.

As a native of Sandy Hook, Connecticut, Doscher entered college with her own powerful perspective. Her younger sister survived the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012.

Dealing with tragedy, trauma, and healing in a new environment in her first year, Doscher supported Team 26, a group of bikers hosted by Gettysburg for Gun Sense that was making the trek from Sandy Hook to Pittsburgh to raise awareness of gun violence prevention and legislation. Then, as a sophomore, she penned a powerful opinion piece for The Gettysburgian on gun violence, cofounded a new club with Emily Dalgleish ’22 called Students Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, and joined Gettysburg for Gun Sense in a meeting with U.S. Senator Bob Casey of Pennsylvania.

“I found my voice here and became mobilized in my passions of writing and acting, so I took on the next passion of ending gun violence,” Doscher said. “Gettysburg College faculty, staff, and students work to actively listen and lift up students to proactively seek solutions to issues.”

Doscher’s advocacy for gun violence prevention grew with the hopes of protecting her new community and preventing any community nationwide from experiencing what her hometown did in 2012.

“I think the same goes for many advocates at Gettysburg who act not only for themselves, but to improve others’ lives,” Doscher said. “We have clubs like an environmental awareness group (GECO), Democracy Matters, and Butterfly Coalition, which was recently established to support undocumented students on campus. They all raise awareness of issues because students seek the betterment of both their lives and the lives of those around them.”

It’s these passions that shape how Gettysburgians lead their lives.

From Laurie O’Bryon ’82, currently serving as an adjudication officer at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, to Churon Lanier-Martin ’20, presenting on poverty at an international symposium in October 2019 in East Java, Indonesia—alums and students alike approach engagement with passion, driven by community.

It may take time for Gettysburgians to find their calling to act, like it did for O’Bryon—it took her 10 years, giving up a law career in Washington, D.C., to make the first leap into pro bono advocacy work in the Philippines with Legal Assistance for Vietnamese Asylum Seekers—but Gettysburg College provides the foundation for purposeful discovery.

“I’m a big supporter of the liberal arts education, and I think that creates an environment for people to explore and to grow,” said O’Bryon, who received a Distinguished Alumni Award in 1998 for her work on the U.S. Campaign to Ban Landmines with the Jesuit Refugee Service. “I think the size of the College allows for a certain sense of community that might be more difficult in larger schools. Now, there are so many outlets within the College for engagement between majors and clubs. The school is structured in a way to really encourage and engage people.”

According to Hutch, Gettysburg College opens the door to the world.

“We graduate a lot of committed public servants for some reason—and that’s down to the College,” Stewart said.

Future growth

“Why not me?”

Throughout his career, Stewart pondered this question. Because neither of his parents attended college, he felt drawn to advocacy work to better our country and world. That included writing a bill favoring homeless veterans that was signed into U.S. law in December 2016.

“It’s hard to get away from experiences that either open your eyes to inequality or this sort of idea of duty to others,” he said. “There are citizens of this country whom we are failing. We are not living up to our promises as a nation. We’re not living up to the idea of democratic egalitarianism, and someone needs to do something about it. Why not me?”

As our nation enters another election cycle, political conversations grow increasingly divisive and more personal. To promote productive civil discourse, the Eisenhower Institute, with locations in both Gettysburg and Washington, D.C., kicked off 2020 by establishing a series to foster deeper, more reflective, and more respectful ways to address disagreement. Here, Gettysburgians learn firsthand from Lincoln that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

“Without the actions taken by President Lincoln, there is no way to know how the nation would have evolved,” Lanier-Martin said. “As Gettysburg College becomes more diverse, there are increasingly more opportunities for more groups to be afforded resources to both learn and advocate for causes and communities in need.”

Since arriving on campus in July, Iuliano has been inspired by Gettysburgians who have used their education to make a difference locally, nationally, and internationally. Through offerings such as Eisenhower Institute programs, Center for Public Service opportunities, and Garthwait Leadership Center lessons, Gettysburg College remains steadfast in its commitment to preparing its students to tackle today’s challenges.

“This orientation toward action and engagement is a defining aspect of the College,” Iuliano said. “It’s also one that traces its roots to our distinctive history and location. As I look ahead, an important responsibility for the College will be to continue to evolve our curricular and cocurricular programs to equip students with the skills and understanding to deploy the political, cultural, and social mechanisms that can bring about change.”

When Iuliano echoed the need for students to remain engaged with the world in September, relying on them to exercise their voices “with courage and conscience” for the betterment of our civic institutions, former Gettysburgians got “goosebumps,” said O’Bryon.

“Very few institutional leaders in higher education will come out and be on record stating that publicly,” Hutch said. “That’s the glory of the four-year liberal arts college in America. … That is a unique seed for generating, teaching, and developing citizens who are ruled by conscience rather than political expediency. I was proud to hear him say that—very proud indeed. … [He’s] embedding within the culture of Gettysburg College to sustain that lifelong fostering of conscience in students and staff.”

Thus, as Hutch puts it, when Gettysburgians want to make their impact, they get on that bus, “whatever bus that will take [them] into the future.”

By Megan Miller

Photos courtesy of Musselman Library and featured subjects

Posted: 04/08/20