It was a time of intense political discord, both on campus and across the nation:

- Movements for social justice, women’s rights, civil rights, gay rights, and the environment;

- A president who championed a “silent majority” of socially conservative voters;

- Unpopular foreign policies hotly debated within the United States;

- And polarizing politics entangled with a newly emerging American identity.

Current commentary? Maybe. But it is also a reflection of the 1960s.

A place for exploration

Then, as now, the College was a place for thoughtful disagreement, civil discourse—and purposeful action. Students and faculty who challenge each other to ask meaningful questions and rethink assumptions in serene times are well equipped to do the same when times are turbulent.

By all accounts, the 1960s were marked by conflict, but Gettysburg College was not a hotbed of political activism in those years. Students were aware of the Vietnam War—it was actively discussed and debated in the Gettysburgian—and there was an occasional demonstration at the Peace Light to speak out against it. But for some, it appeared that Gettysburg College remained untouched by the anti-war protests and political turmoil that defined the decade.

“It is apparent that student unrest is prevalent on many college campuses throughout the country,” Sandy Treen ’70, president of the Women’s Student Senate, wrote in a pamphlet distributed on campus in 1969. “In light of this it is perhaps not surprising that Gettysburg College is involved in this general attitude. That is, not unless you are a student at Gettysburg College. Because, up until recently, this College could possibly have been recognized as the most apathetic of all such institutions. Then one Saturday morning, the campus awoke.”

That stirring was inspired by the larger culture of social activism intertwined with anti-war protests. Students occupied the student union building overnight in early March 1969, calling for a greater voice in the policies that governed them on campus. They petitioned College President Carl A. Hanson for a daylong moratorium to address their concerns.

Hanson approved the event and cancelled classes for two days in April in order to accommodate it.

“I support the idea of a gathering of all parts of the College for serious discussion of our problems and opportunities,” Hanson wrote in a memo on March 16, 1969. “Thus, the proposal for a ‘moratorium’ has my support under the assumption that its formulation includes all parts of the College and permits serious exploration and follow up of matters of concern and interest.”

Topics brought forward by students included the College’s dry campus designation; differences in policies governing male and female students; the desire for a racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse student body; and integration of academics that covered more interdisciplinary and politically relevant topics. Faculty members, campus administrators, and students were asked to speak about these issues and how they impacted the future of the campus.

Many of the outcomes became integral to what Gettysburg College students experience today—others, such as diversity, are continued works-in-progress. At the time, the participants weren’t certain of their legacy. Reflecting on the moratorium, Jim Henderson ’71 wrote, “The moratorium did succeed in producing the dialogue and communication which it set out to promote, but, of course, the question of ‘how much?’ can really only be adequately answered by resultant action.”

Honoring action and sacrifice

While students played a role in effecting cultural and policy changes on campus, a number of Gettysburgians joined the national discourse about foreign policy through their service in the Vietnam War.

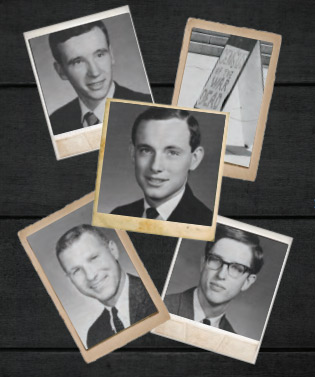

The exact number of Gettysburgians who enlisted or were drafted into service is not recorded. What is known is that 14 alumni made the ultimate sacrifice—each gave their life during the course of their service.

This fall, a memorial listing the names of these Gettysburgians will be dedicated outside of the newly completed College Union Building renovation. Many of them were not much older than most current students are now—calling into sharp focus the cost of war and the individual stories that are often lost to the war’s narrative.

That, according to Susan Colestock Hill ’67, is the exact reason she feels this campus memorial is so important. One of several alumni who have spearheaded this effort, Hill lost both her brother, Lieutenant JG John M. Colestock ’65, and her first husband, Captain Robert L. Morris ’66, to the war.

Colestock had been actively involved on campus—he chaired the College judicial board, was a member of Phi Gamma Delta, played on the soccer team, and excelled academically as a biology major. He went to work for a pharmaceutical company before the draft prompted him to enlist in the Navy.

Even then, he stayed in close contact with his sister, inviting her to visit while he was in flight school in Texas.

“At that time, the pilots were able to take family members into a Navy jet and onto the runway for an aborted takeoff,” Hill recalled. “John arranged to let me join him in the plane. I suited up, climbed in the back seat, and off we went to the end of the runway!”

Morris had a lifelong dream of being a pilot in the Air Force. He was a member of the campus Air Force ROTC, which helped him prepare for his service. Morris excelled athletically as a member of both the baseball and the basketball teams. He majored in health and physical education, joined Tau Kappa Epsilon, and served as the chapter’s president.

Both men died during their service, leaving behind wives and children—Colestock, a son, and Morris, two daughters.

Hill shares these stories not to mourn her family’s losses, but to underscore the importance of remembering what was lost for so many people of her generation.

“The primary story we want to preserve is one of countless young men who were students one day and soldiers soon after leaving college,” Hill said. “This is where we planned and prepared for our futures and tested our wings in campus life. We grew up together on the campus. It’s from here that we were launched to make our way in the world.”

Of the many names that appear on the memorial, First Lieutenant Stephen H. Doane ’70 stands out as the College’s only Medal of Honor recipient. As a student, he was on the wrestling team and became a member of Phi Kappa Psi, despite never finishing his initiation before he withdrew from the College and fulfilled his lifelong ambition of serving in the military.

He kept the lessons he learned on campus close to mind during his service, using them as motivation to work hard and achieve well, as his father once wrote to then Dean of the College Basil Crapster. To Doane, that often meant looking out for his fellow soldiers, especially once he was promoted to platoon leader. He took great pride in his platoon’s low casualty rate.

He died two years into his service—at age 21—when he carried an activated hand grenade into an enemy bunker in order to save the lives of the men in his platoon.

“The memorial will preserve these stories and will record the character of these men in hopes of remembering and studying extraordinary times and responses to those times,” Hill said.

Lieutenant Colonel Bill Bock ’66 is a member of the alumni committee working with Hill, Tom Delavergne ’66, Tom McCracken ’66, and Dave Reichert ’66 to fund and establish the memorial. He views these stories as an integral way to access the larger narratives of Vietnam while also learning some critical lessons.

“The primary story we want to preserve is one of countless young men who were students one day and soldiers soon after leaving college.” -Susan Colestock Hill '67

“History is people,” Bock said. “With this memorial, we are sharing a piece of history, but also the stories of the young men who were students one day and soldiers the next.”

Bock gives the example of Stephen Warner ’68, an alum well-known for his service in the Army’s public affairs office. Warner was killed in Vietnam in 1971, three days before his service was done. He left the College his $10,000 servicemen’s group life insurance policy, as well as two footlockers of photographs, journals, diaries, and letters.

“You see his name on this memorial, and you know he served—and died—in Vietnam,” Bock said. “But then you see his picture, and he’s this serious-looking guy staring out at you in his black-rimmed glasses. You learn his story and realize he was a committed student who went on to Yale Law School. He was opposed to the war, actively spoke out against the war, and yet lost his life in it. His photographs capturing the lives of soldiers will be viewed and appreciated for generations.

“Once you learn their stories, there is a sense of humanity…of connection…current students may realize these young men from another time weren’t so different from themselves.”

“Once you learn their stories, there is a sense of humanity…of connection…current students may realize these young men from another time weren’t so different from themselves.”

Remembering a complex time

While the memorial will stand outside of one entrance to the College Union Building, an exhibit building on the stories of the men identified on it will be housed in Musselman Library. Gettysburg College Archivist Amy Lucadamo ’00 has been working with the families and classmates of these men to acquire the materials needed to tell their stories—both as students and as soldiers.

“It matters, the farther away we get from historic events, that we are able to humanize the people involved in them and not look at them as people who are wholly different from us who lived in wholly different times,” Lucadamo said.

It’s all about how you access the past, she claims. Not only can it help you understand the complexities of another time, but it can also give you a sense of how to move forward in your own time.

“It’s not about casting a moral judgment on what happened,” Lucadamo stated. “You don’t have to agree with the war to be able to respect their experience in the war.”

In fact, the national memorial located in Washington, D.C., was built 10 years after the Vietnam War concluded. Much of the turmoil of the times and the nation’s need to heal festering wounds can be found in the symbolism of the memorial—from the shape of the wall to the reflection of visitors when looking at the names of the soldiers who were killed or missing in action.

“It’s starkly different from the way in which other war memorials were built and created,” said Civil War Era Studies Prof. Ian Isherwood ’00. “There is no overt heroism or triumphalism in that monument, just a deep feeling of sadness and tragedy. It’s a very poignant symbol to go back to—a symbol of tragedy and mourning for a generation of American soldiers.”

According to Isherwood, the Washington, D.C. memorial captures a shift in the American narrative surrounding the war as they moved away from the political divides of the time and tried to construct a consensus about the long-term meaning of the war.

“You see a shift from the poles of radical anti-war feelings and dogged patriotism toward a more nuanced approach in how we look at the war,” Isherwood continued. “For the first time, you see this idea of the soldier as someone we can still honor regardless of our feelings of what the war was waged for. Veterans start to reclaim a sense of agency as people come to grips with what it means to be anti-war and pro-soldier.”

Professors are challenged to capture the complexities of the era and our shifting views about it. Both Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Prof. Emerita Janet Powers and history Prof. Tom Dombrowsky—who have taught courses on the Vietnam War since the early 1990s—say they observed a notable shift in the level of awareness students have about the war when they arrive on campus.

“For a while after the war, people conveniently didn’t want to talk about it. That often included high school teachers,” Powers said.

Whenever she taught a course on the Vietnam War, she would always ask students about their connections to the war and how they’ve learned about it.

“Overwhelmingly, the answer was that their father or their uncle had fought in the war, but that they never spoke about it,” Powers recalled. “For many of them, that was it. It was a divisive time, and generally, people avoided the topic.”

Both she and Dombrowsky were adamant in their charge to have students critically examine the war from many different perspectives in the first-year seminars they offered.

“It matters, the farther away we get from historic events, that we are able to humanize the people involved in them and not look at them as people who are wholly different from us who lived in wholly different times.” -Amy Lucadamo’00

For Powers, that meant balancing course literature with American and Vietnamese authors, all of whom had some connection to the war or discussed the war in their work. She would also take students on a field trip to Washington, D.C., to visit the Vietnam War Memorial, lay flowers underneath Warner’s name, watch the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and learn about Vietnamese culture through their cuisine before returning to campus.

Dombrowsky used films, guest lectures, and debates that examined many different aspects of the war—from key policy decisions leading up to the war to the anti-war movement across the country, as well as the ordeal of soldiers long after they returned.

“Essentially, I wanted them to understand as much as they could about the war from a factual basis— not a political viewpoint or Hollywood narrative,” Dombrowsky said. “You’ve got to address the fact that there were incredible protests and polarization—you can’t glamorize the anti-war people who advocated for an end to the war, just as you can’t glamorize the soldiers who fought in it. The reality, as with most things, is mixed up between all of these various perspectives, but I want my students to reach that conclusion through their own analysis.”

Today, there are plenty of classes that incorporate lessons about Vietnam, even if the focus of the course isn’t wholly on the war itself. One example that stands out: political science Prof. Caroline Hartzell’s course, Political Economy of Armed Conflict, in which she connects students with veterans of many different wars to discuss related policy issues.

“While we don’t spend too much time on any particular conflict, all of my students choose a research topic and complete an oral history where they talk with a veteran,” Hartzell said. “What I’ve found is that students just really appreciated getting to know veterans and hearing their stories.”

According to Hartzell, some students continued to stay in touch with the veterans they worked with after their projects were completed or found new ways to examine the issues that surfaced through their conversations.

While there are no easy answers or simple narratives about the Vietnam era—or any period of conflict, Gettysburgians stand on the historical past as they debate, remodel, and contemplate the future.

“I don’t believe that history repeats itself, but if there are no lessons to be had from the past, then my job would be redundant,” explained Isherwood. “We can always extract lessons from events in the past, and I think there are many great lessons we can learn from Vietnam.”

Among them, he claims, are lessons about credibility and transparency from elected officials and the government as a whole, especially when mandating a draft or rapidly escalating a war.

For Hill, she hopes the College memorial and engaging in the stories of those who served in the war will inspire students to ask meaningful questions about how they lead their own lives.

“In creating this memorial, I’m constantly wondering about the questions and conclusions that will generate in current and future Gettysburg students regarding their [personal] devotion to duty and ideals,” Hill said. “Will those students reflect differently on freedom, courage, and responsibility because students of an earlier time—just like them in age and dreams—approached adulthood with a draft notice in their pockets? Will the losses and sacrifices of our generation make a difference now and in the future?”

Gettysburg Remembers

Captain Ronald F. Thomson ’60

Corporal Edgar B Burchell III ’62

Captain Joseph P. Murphy ’63

Lieutenant JG John M. Colestock ’65

Ensign James M. Ewing ’65

Ensign Andrew L. Muns ’65

First Lieutenant George A. Callan ’66

Captain Robert L. Morris ’66

First Lieutenant Charles H. Richardson ’66

First Lieutenant J. Andrew Marsh ’67

Specialist 4 Stephen H Warner ’68

Captain Daniel W. Whipps ’69

First Lieutenant Stephen H. Doane ’70

Captain Millard R. Valerius, ROTC Instructor 1962–1964