Almost four years ago, Kenneth “Kenny” Knickerbocker ’07 moved to Sumba in Indonesia, a remote island about an hour-plane-ride from Bali and roughly double its size, with less than 20 percent of its population.

As he describes Sumba via Skype, it’s hard not to picture an oasis—quiet beaches perfect for surfing, nature untouched—but in reality, for many Sumbanese villages, access to vital resources such as potable water, quality healthcare, and education, is limited.

Last year, Knickerbocker accepted a role as the general manager of the Sumba Foundation, which works to provide these resources to local villages.

“It’s beautiful, but life for an average individual is very tough,” said Knickerbocker.

“Our mission is to provide humanitarian relief without altering or changing the cultural aspects of their [Sumbanese] day-to-day lives,” he said.

The Nihiwatu resort, where the foundation is located, was first designed by Claude Graves and his wife, Petra, to be a surf haven in the late 1980s. More recently, Chris Burch an American billionaire, and James McBride, a South African hotelier, bought the site with the goal of turning it into one of the world’s most exclusive resorts. Graves started the Sumba Foundation with Sean Downs, an American businessman, in 2001.

Knickerbocker held positions in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Singapore, and Malaysia, before managing Nihiwatu, and now, the foundation’s programs. The resort, although a separate entity, houses and supports the foundation, providing the resources it needs to run so all donations go directly towards supporting the foundation’s initiatives.

Their goal, he said, is to improve the daily life of villagers on the island “without detracting from the cultural elements that have made so many people fall in love with Sumba.”

Knickerbocker’s daily work involves overseeing the foundation’s key projects, which include providing people with access to water, eradicating malaria, and hosting educational programs for children.

“Before even the hotel was established, women and children were walking several miles every day to get usable water,” he said. “Now we’re providing 25,000 people with access to potable water, daily.”

The foundation has also focused efforts on training nurses and lab technicians and establishing malaria clinics.

“We have been working to eradicate malaria, primarily in our area, but with the goal of removing it from the island entirely,” he said.

Since the program’s infancy, Knickerbocker said malaria transmission rates have been reduced by more than 93 percent. And through the training programs, the foundation has extended its impact.

“We’ve graduated 360 students from the Malaria Training Center,” he explained, “and they help diagnose 150,000 patients in their localized areas every year.”

Knickerbocker’s journey to working at the foundation was winding, and not just because he’s lived all over the world. A lifeguard, water safety instructor, and a self-described “beach boy” when he started working in the hotel management industry, Knickerbocker has also held positions as a concierge, and in public relations, sales and marketing. At Gettysburg, Knickerbocker was a studio art major. At one time he thought about becoming an architect, so he also spent a semester studying in Denmark, fascinated by the country’s architecture.

Today, although seemingly unrelated, Knickerbocker still draws on and makes connections between these experiences.

“When I was at Gettysburg I studied studio art, and when I came to Sumba I fell in love with the artisanship and craftsmanship,” he said.

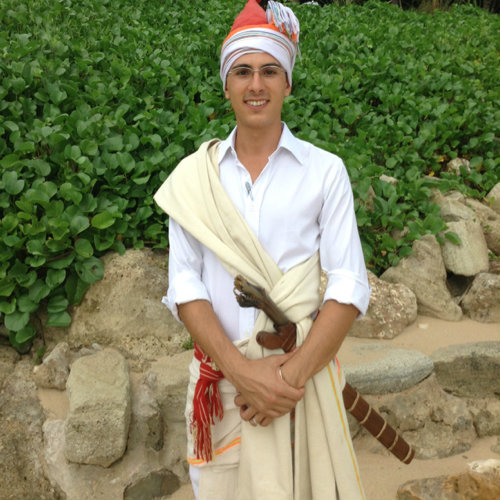

Indonesia is known for its textiles; Knickerbocker became especially interested in the pictorial depictions of Sumbanese culture through ikat, a dyeing technique used to pattern textiles. He completed his senior capstone on sculpture, so he’s also fascinated by the stone carvings of religious gods and ancestors that are prominent in Sumbanese villages.

More importantly, Knickerbocker has come to learn and deeply appreciate how these cultural representations demonstrate the Sumbaneses’ connection to their roots and history, and how to preserve their significance through his work.

“[My experiences at Gettysburg] made me realize the world is so much bigger than we all are,” he said. “Whether here or abroad, no matter what your major may be, it’s irrelevant—if you have the opportunity to make an impact in someone’s life, you should take advantage of it.”