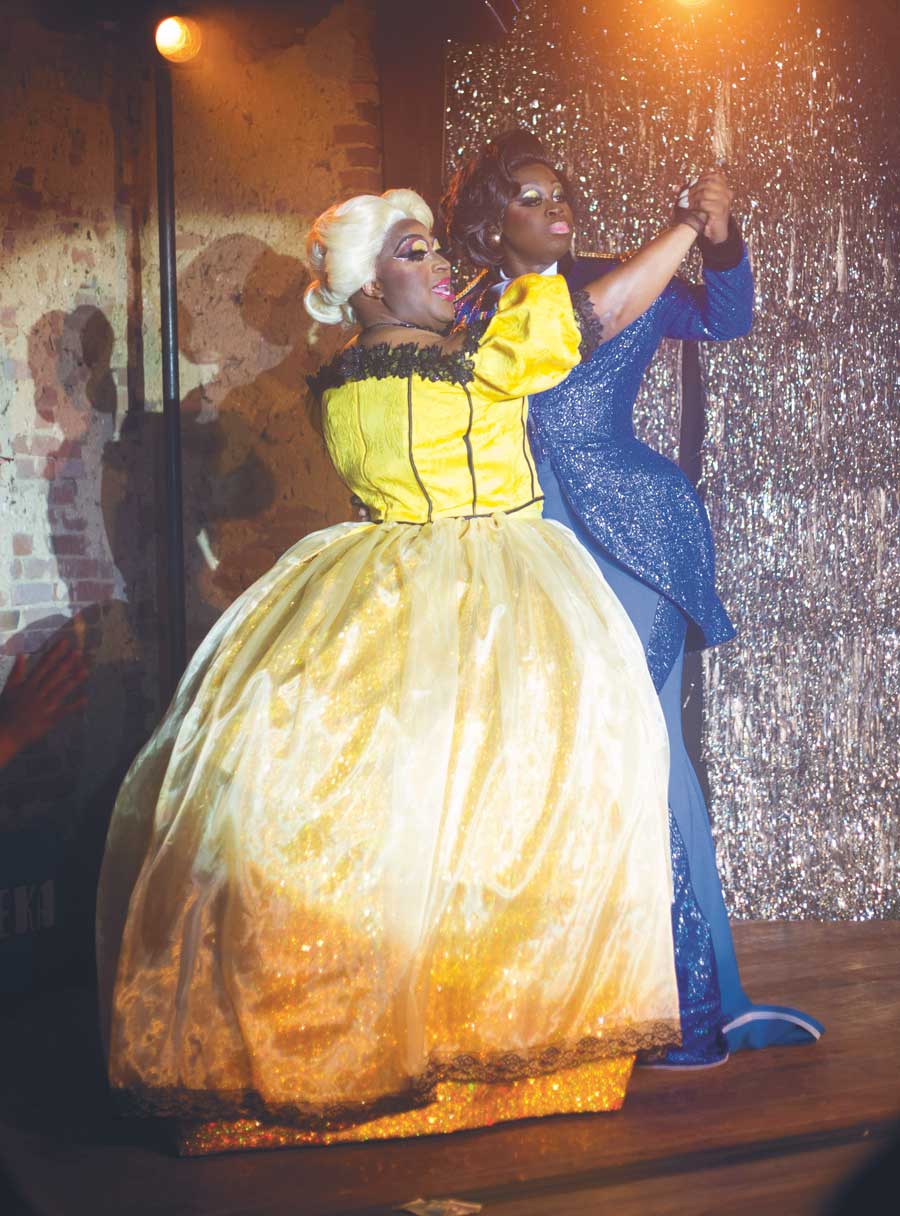

Backstage at Battlefield Brew Works & Spirits of Gettysburg Distillery, Darrylina of the House of Joneses’ glam entourage was working its magic, transforming her into the Southern belle she never knew she wanted to be.

A blonde wig with tightly tied ringlets was placed on her head like a crown. Her cheeks and lips were kissed with a matching red tint, and her eyelashes grew an inch with the help of extensions. Hugging her curves—all credit due to a breath-stifling corset—was a buttery, custom-made gown that melted from her hips to the ground.

Darryl Jones, the Senior Associate Director of Admissions and Coordinator for Multicultural Admission at Gettysburg College, admits he never really gave dressing in drag much thought. But that was before he was recommended by the co-organizers of Gettysburg Pride—Corey Williams, Karl Held, and Chad-Alan Carr—to be a straight ally in HBO’s debut episode of “We’re Here,” a six-episode, real-life series aimed at elevating LGBTQ voices in small-town America.

“I asked some gay friends of mine in town about who they all felt was a strong straight ally and they all said, ‘Absolutely Darryl Jones,’” Carr said. “I connected Darryl with the casting director for HBO, and the rest is history.”

Early on in filming, Jones said the producers asked him what he thought about drag, and, not knowing enough to shape an opinion on the spot, he replied with curiosity, “Well, what is it?” After a brief primer on the basics—everything from hair and makeup to costume and choreography—Jones responded, “If that’s what people want to do, I still embrace them. They’re still human.”

To Jones, being inclusive is more than just sharing a string of accepting words; it’s about living out those words. “Being inclusive means that you actively embrace. It’s not about saying, ‘Well, I tolerate you. I accept you. I’m OK with you existing.’ It is fully embracing who people are,” he said. “If I don’t outwardly embrace and vocally defend people who are different from me, then how can I ask others to do that for me, a Black man?”

When the producers later asked him whether or not he’d be willing to embrace the experience of dressing in drag himself, Jones breathed life into his drag queen alter ego: Darrylina of the House of Joneses’—a spoof on a nickname given to him by former Admissions employee, Valerie Schwartz ’03. “I’ll do it,” he said, acting on his lifelong belief in the value of walking in the shoes of others—even if it was just for a short while (he’s since realized that his size 12 feet were not made for stilettos).

We’re here

When Jones received a phone call from an unrecognized number in June 2019, he assumed it was a spam caller, and he let it ring through to voicemail. Little did he know, it was HBO on the other end. At the time, he was spending the warm, summer months with family in Evanston, Illinois, but a few days later, he was on a flight back to Gettysburg with nothing more than his suitcase and a dubious description from producers, who intended to keep the filming strictly confidential.

“I knew absolutely nothing,” Jones said. “I was just told they were filming a program with a social justice theme. They said they’d arrange a flight for me, and a car would be waiting.” Nonetheless, he showed up.

Wearing a Poor People’s Campaign T-shirt that read, in large, block letters, “Fight poverty NOT the poor,” Jones walked through town and around Lincoln Square to the Blue and Gray Bar and Grill on the corner of Baltimore Street, as he—a Gettysburg native—had done many times before. But this time, cameras followed him. Inside, the restaurant buzzed with conversation between locals and out-of-towners exploring the rich Civil War history found on every corner here. Among the patchwork of people was reality television personality and Black activist Caldwell Tidicue, better known as Bob the Drag Queen.

“Bob was just in regular gear—no drag. So, I just thought, OK, well here’s this African American, tall dude who I’ve been told by the producers is ‘the talent’ and we’re ordering lunch,” Jones said. “I had no idea who he was at the time.”

As they exchanged small talk and perused the menu, Jones decided on a Confederate Burger. Bob ordered one, too. At most restaurants, when you think about picking a side, you’re often left to debate how you want your potatoes, but at the Blue and Gray, picking a “side” has a twofold meaning—not only do you have to choose from among chips, french fries, or sweet potato fries with your burger, but you also have to choose Union or Confederate.

Each Battlefield Burger is named after a Civil War general—Gens. George Meade, Winfield Scott Hancock, James Longstreet, and Robert E. Lee being among the options—and comes skewered with either an American flag or a Confederate flag. It wasn’t a politically motivated decision for him, Jones said. The burger just sounded the most appetizing.

“This is footage that didn’t make it into the episode, but when my server brought me my burger, she didn’t bring the flag, and I said to her, ‘Oh, no, I want you to bring the Confederate flag that I know you put in these burgers, and I want people to see you giving that to me, because that’s what you do, isn’t it?’ There was a little embarrassment on her part, but I told her, ‘Look, if we’re going to be served this thing that you are making money from, don’t treat me differently.’”

These conversations about Jones’ experience as a Black man in Gettysburg, like the one they shared at the Blue and Gray, continued after he and Bob left the restaurant. While many of the conversations about race didn’t air with the episode due to episode time constraints, for Jones, they were just as significant as those that made it into the show—shining light on the experiences of another marginalized community—and in them, Jones felt heard.

They spent the remainder of the day walking around the back end of Pickett’s Charge on the battlefield and talking with a Robert E. Lee living historian. “We asked him: ‘So, what do you think about the Confederate flag?’ And he said, ‘As Robert E. Lee, I tell you there is one flag, and that is the American flag. The Confederacy lived in a moment in time. It is done. Let’s move on and unify the nation.’”

Gettysburg, PA

It was here that bullets rained down as the Union and Confederate armies clashed during the decisive Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Months later, it was here that David Wills Class of 1851 invited President Abraham Lincoln to deliver “a few appropriate remarks” at Soldiers’ National Cemetery, and townspeople, students, and faculty listened, wide-eyed, as he delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address. It was here that President Dwight D. Eisenhower— a captain at the time—took command of Camp Colt during World War I, later returning to call Gettysburg home post-presidency.

Considering the breadth of this rich historical context, Jones said it’s not surprising that HBO chose Gettysburg as the location for its debut episode of “We’re Here.” Throughout history, Gettysburg was a place of great significance to abolitionists, soldiers, and presidents. And today, it remains as such to locals, the million or so tourists who visit each year, and passionate, talented students who are looking for a place—a college—that inspires them.

“If people really broke down what the Gettysburg Address is, if people really broke down the land on which the College was founded and who founded it, and if people looked at President Eisenhower’s history—a man who believed enough in integrating schools to actually make it happen by giving armed National Guard escorts to people who were doing it—then we’d have a chance to market ourselves as not being new to social justice, but having it be a part of our DNA and entire existence,” Jones said. “It’s not to wipe clean any ills, but that’s a pretty powerful statement we can make that a lot of other [colleges] can’t.”

Woven into the 189-year-old fabric of Gettysburg College is a community of changemakers who recognize that diversity, equity, and inclusion are abiding battles—battles that made strides during the Civil War but didn’t end in 1865. In pursuit of a better, more just and unified world, they must be fought every day.

“When I joined the Admissions team at the College in 1985, I think we had around 10 students of color in the entering class. And this year, [in the Class of 2024], there is 24 percent domestic diversity,” Jones said. “We’ve certainly had the good fortune of having great leaders over the last several years—people pushing for change instead of just talking about it. But our goal is not to intentionally diversify for the sake of doing it. It’s to get our campus to look like the rest of the United States in terms of ethnicity. And we’re not there yet.”

A more unified and just world starts here, and elsewhere, in the minds and hearts of those, like Jones, who see strength in difference. There is urgency in this work, and by actively seeking and listening to the voices of underrepresented populations, reflecting on the highs and lows of history, and evolving, we are on the move.

“We have work to do as a community, and more broadly, and Gettysburg College can be an institution that leads that work. We have a platform to do it, and it’s time,” Jones said. “Education can lead it, but mostly people who care can start the conversation and then move their feet to make a difference.”

Leaving a lasting mark

Following the lead of Bob the Drag Queen, who strutted on stage in her shimmery soldier getup to the beat of En Vogue’s 1992 hit “Free Your Mind,” Darrylina split the silver tinsel curtain and was met with blinding lights and the roar of a packed house. All Jones could think about was making it through the performance—remembering to breathe and not stumbling over his own feet.

It wasn’t until after the lights went dark, the crowd went home, and the costume came off that the experience took on a deeper meaning for him.

“Now I get it,” he remembers saying to Bob on the last night of filming. “Bob chose this song—‘Free Your Mind’—intentionally. Free your mind and the rest will follow. Be colorblind. Don’t be so shallow. Meanwhile, at the time, I was just thinking Bob likes En Vogue. But something made it all come together for me that last night. In that moment, I turned to Bob and thanked him, because what he created was truly brilliant—the Southern belle costume, the song, and the message. Not only was I taking a step out of my comfort zone to be an active ally in the LGBTQ community, but all the while, Bob was trying to get others to see me, too—to really see me, and what it’s like to live in my skin.”

Available to stream across the country on HBO and HBO Max, the first season of “We’re Here,” and its unifying messages, have the power and platform to reach far beyond Gettysburg. Jones hopes that those who watch the debut and subsequent episodes take a look inward and challenge themselves to understand and embrace someone who is different from them—whether they’re LGBTQ, Black, or identify as a member of another marginalized community.

“We all need to be listeners, and we need to put the ‘unity’ back in the word ‘community,’” Jones said. “If we all joined together—both people of those backgrounds and the allies of people from those backgrounds—that’s how you make the difference. That’s where the power to create lasting change is.”

Jones is humbled by his newfound coast-to-coast community that has watched “We’re Here” and thanked him for being an ally. But he reminds those individuals, “I’ve always been an ally, and I always will be. The HBO show didn’t make me that.” He holds the same withstanding charge for others, too.

“It’s great that more people are reading about anti-racism, [LGBTQ rights, and other social justice issues] and have the desire to educate themselves, but I’m interested to see how sustained people’s efforts are after they read the last chapter and have the last discussion—or, after they watch the HBO show,” Jones said. “What’s next?”

By Molly Foster

All photos courtesy of HBO

Posted: 05/03/21