When Stephen Nowlan ’72 was a first-year student, he had the idea for Symposium ’70. The series of events would earn its place in College history—and receive official recognition from POTUS—for facilitating discussions around pertinent issues during a notably tumultuous period in U.S. history.

Symposium ’70, one of a series of student-driven movements at Gettysburg College during the peak era of activism, was the brainchild of Stephen Nowlan ’72. A natural politician, Nowlan conceived the idea of turning the annual campus “awareness week” into something much bigger. Classes for three days in March 1970 would be canceled for speeches by, and discussions with, leaders in politics, media, education, business, race relations, philanthropy, and social activism.

Nowlan began pitching the idea almost from the moment he arrived on campus as a first-year student in September 1968. It was a wildly ambitious concept, but Nowlan’s idea of an alternative to the disruptive student behavior on other campuses had legs. As Junto, the publication of the College’s chapel council, put it in October 1969, “It’s more than canceling classes for three days and rapping with your roommate. It is an opportunity to show the world that we have accepted our responsibilities as college students. … It will give us a chance to share our ideas and ask the questions that are confronting our generation.”

Symposium ’70 gained traction with Student Senate leadership, several trustees, and faculty (notably Philosophy Prof. Norman Richardson, Religion Prof. John Loose ’51, and Political Science Prof. Kenneth Mott P’07). Trustees, the Class of 1969, and the Senate provided seed money. Nowlan and a small cohort, including Douglas Stewart, Jr. ’72, Anthony Yanketis ’71, and Donald Smith ’71, compiled lists of potential donors and well-known speakers. It seemed, for a time, that the idea might catch on with President Richard M. Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, given their antipathy toward what they considered to be destructive student protests. Despite Nowlan’s contacts in Washington, that did not quite work out, though Nixon and Agnew each sent letters commending the enterprise.

Gettysburg College President C. Arnold Hanson was skeptical about the ability of students to pull off such an ambitious plan. But support for Nowlan’s idea was sufficient that Hanson grudgingly endorsed it.

The electricity was palpable

During the fall of 1969, when thorny logistical and public relations issues arose, it seemed that things might fall to pieces. Gettysburgian editors criticized the effort as an ego trip. Anticipated corporate donations were not coming in. And Nowlan was in deep academic trouble, having devoted virtually all his time to planning the Symposium. By December, Senate President Geoffrey Curtiss ’70, P’04 stepped in to steer the ship to port in the face of serious headwinds.

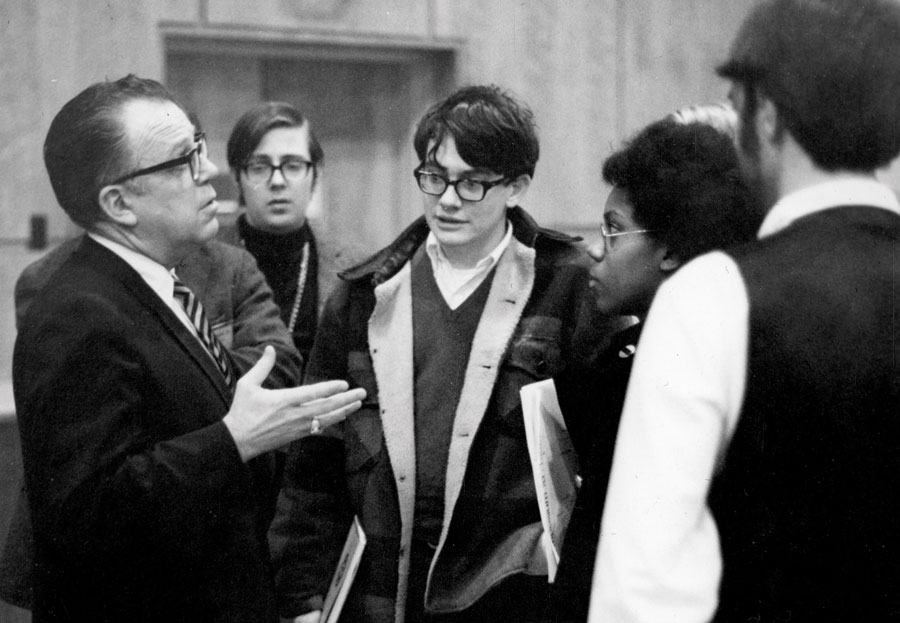

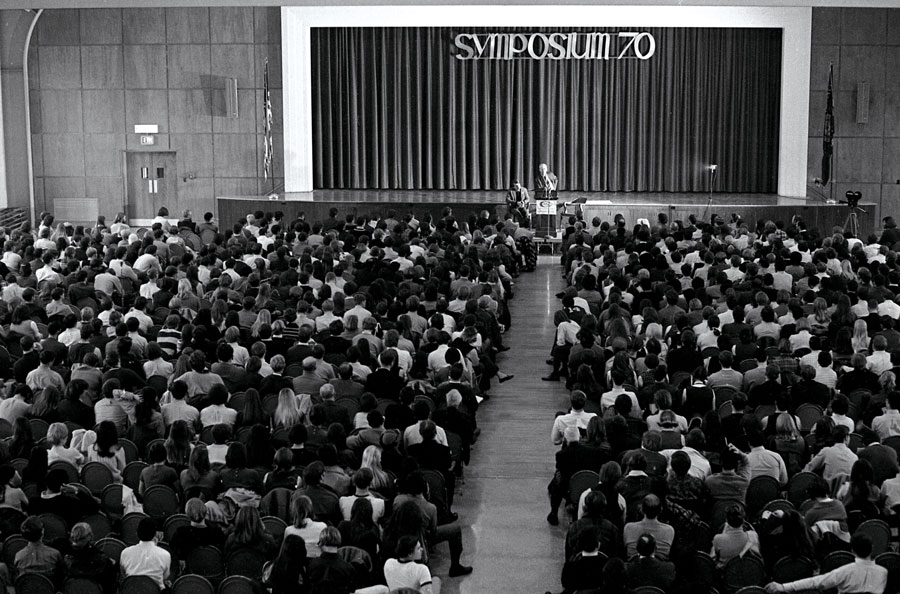

The event turned out to be a historic success. Virtually every contracted speaker showed up for the Symposium between March 11 and 13, participating in formal lectures that drew upwards of 800 people and smaller discussions, held in virtually every space available on campus. The electricity was palpable. Nationally syndicated columnist Carl Rowan, socialist writer and activist Michael Harrington, former U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, and former Attorney General Ramsey Clark drew among the biggest crowds.

Perhaps the most meaningful action occurred in the small-group sessions with Sunset Strip preacher Arthur Blessitt, Chicago-based community organizer and author Saul Alinsky, Village Voice writer Nat Hentoff, and the head of the Boy Scouts of America, among others.

A reasonable estimate is that 80 percent of Gettysburg students attended one or more of the Symposium’s events.

Bob Cox ’71 recalled “the unique bonding that took place between students and faculty as both groups mingled in classrooms, dorm lobbies, fraternity houses, and private living rooms listening to real-world heroes relate real-life experiences. This exposure helped expand our consciousness beyond southeast Pennsylvania without focusing on southeast Asia, where so much of our energy was directed in those days.”

President Hanson made clear to all concerned that this event was a one-off. There would be no Symposium ’71, nor another awareness week. But what Nowlan, Curtiss, Smith, and company pulled off was memorable and meaningful. Student activism, they proved, could produce civil, productive dialogue across a wide spectrum of viewpoints. Sensibilities were impacted. Minds were opened about ways to pursue constructive changes in an imperfect society. Sounds like the best of a liberal arts education.

by Michael J. Birkner ’72, P’10

Posted: 04/09/20