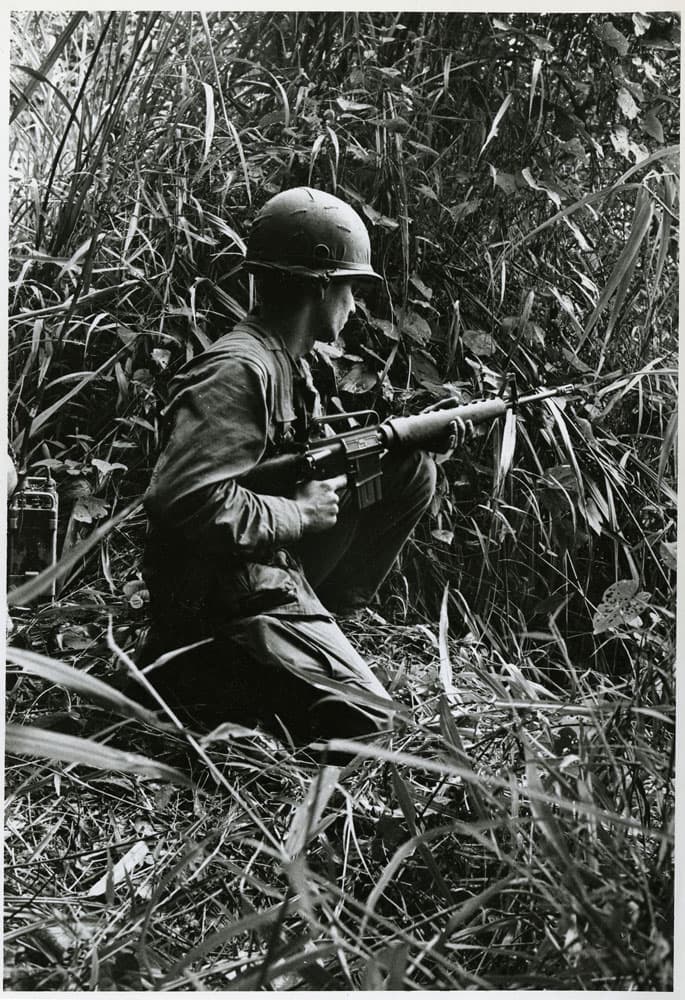

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

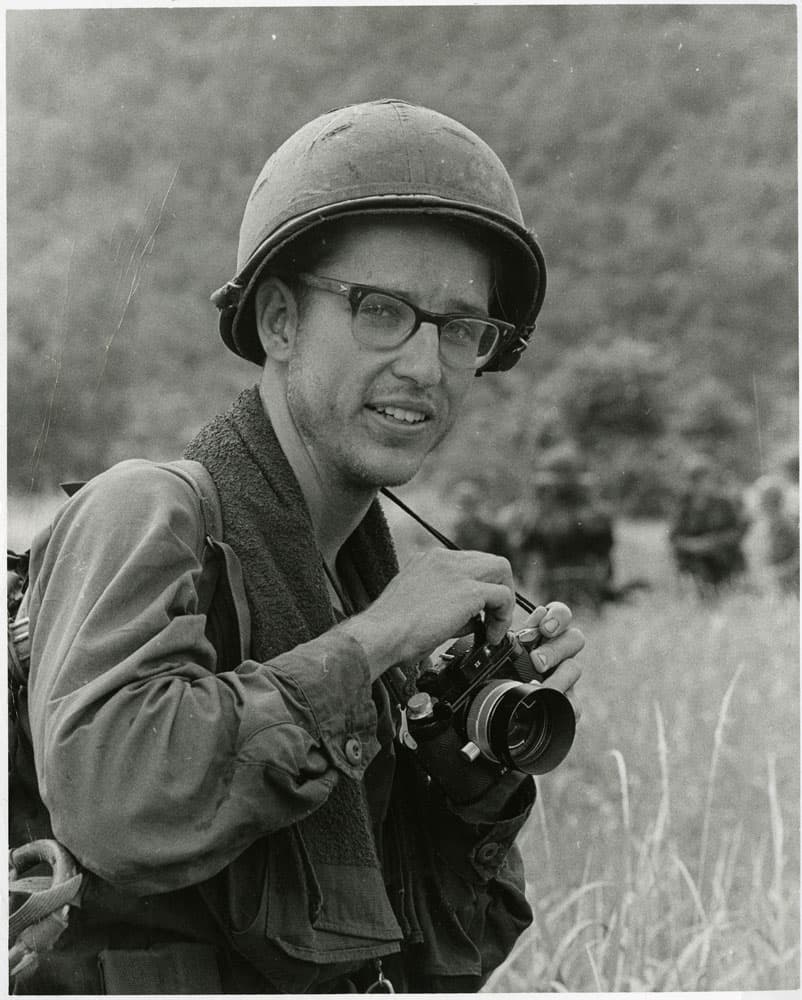

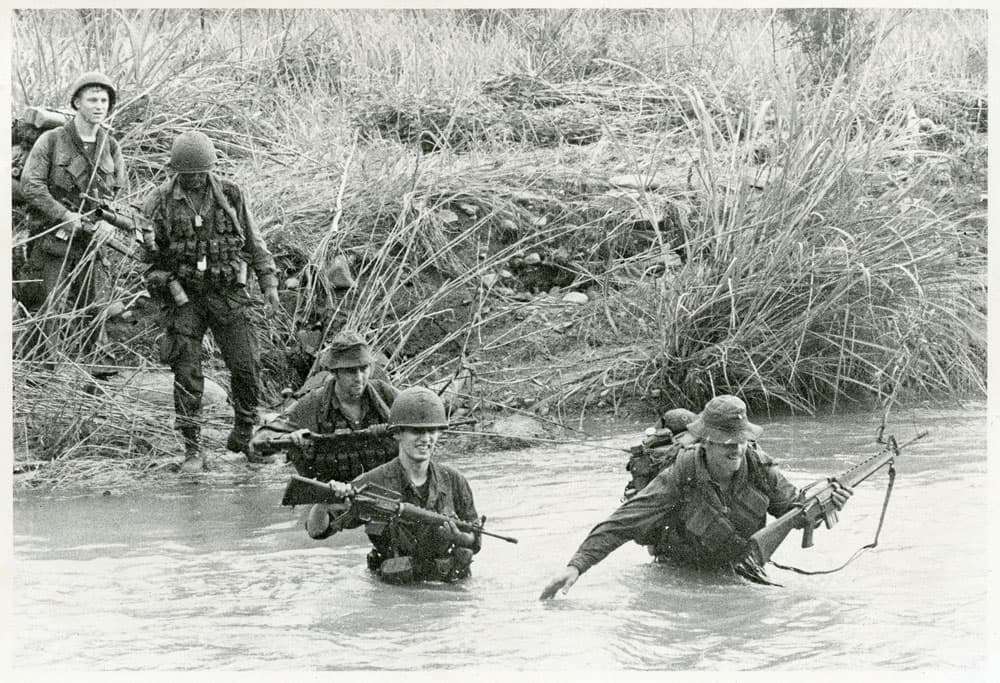

In central Vietnam, a few miles from the village of Khe Sanh and what remains of the American combat base that shares its name, a quiet road winds its way through dense jungle. The road was originally built in February 1968 by a team of Army engineers in the area of operation flanked by the Demilitarized Zone to the north and the Laotian border to the west. In February 1971, another team of Army engineers were joined on their assignment by a group of combat troops, there to protect the construction crew as they made their way through territory contested by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Also in their midst was an outlier: Stephen Warner was neither a combat soldier nor an engineer but rather an information specialist assigned to the Public Information Office located several hundred miles to the south at Long Binh Post. A young man of slight physical build with glasses and a crooked grin, Warner was far from the stereotypical Army soldier. He was, in fact, a devoted pacifist who hated the war and fiercely protested against it before arriving in Vietnam. His path from antiwar activist to soldier highlights the often contradictory realities of military service during the Vietnam era.

Stephen Henry Warner was born on 21 February 1946 in Skillman, New Jersey. His father was a patent attorney for Johnson & Johnson and his mother was a homemaker who raised Warner and his younger sister Victoria. Warner was an intelligent kid who loved to read and spend time outdoors. He was an excellent student and graduated from Princeton High School in 1964. He then continued his studies at Gettysburg College, a small liberal arts school in Pennsylvania. It was during his time at Gettysburg that Warner became a vocal critic of the war in Southeast Asia.

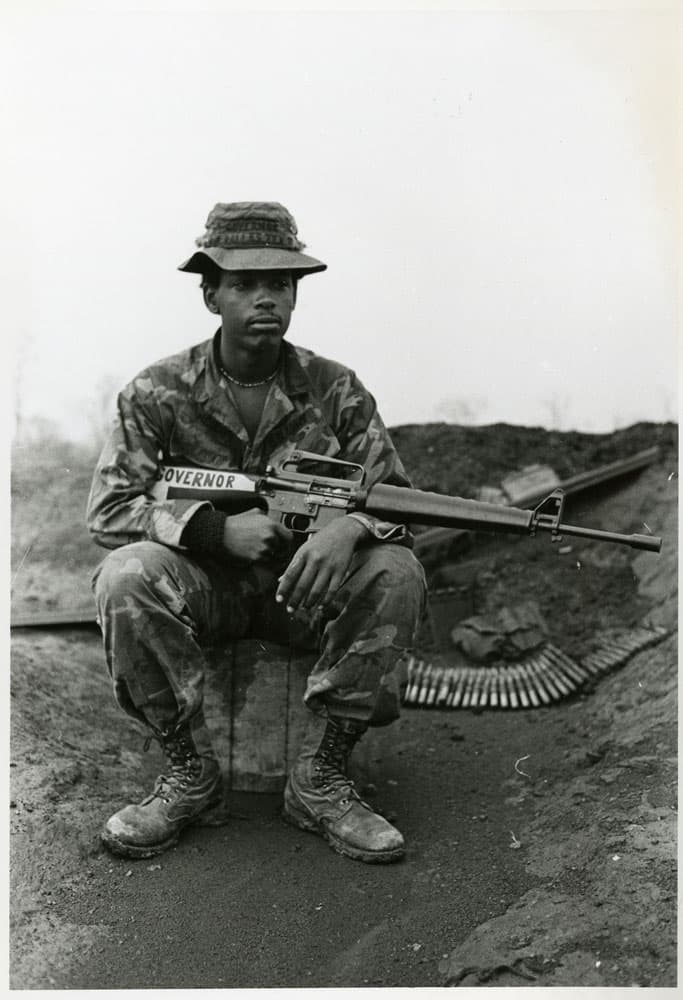

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

As American involvement in Vietnam continued to escalate during the 1960s, antiwar sentiment began to grow. The most vocal opposition to the war often was found at colleges and universities across the country, and while at Gettysburg, Warner became an active leader in the antiwar movement on campus. He began by writing articles for the school newspaper, eloquently expressing his opposition to the war. In 1966, he co-founded an ad hoc committee of students opposed to the Vietnam War and later participated in the 1967 March on the Pentagon. Warner continued his activism until he graduated with honors from Gettysburg College in 1968, earning a degree in American History.

Following graduation, Warner planned to attend law school. He also knew, however, that doing so would put him at risk of being drafted. Recent changes to Selective Service regulations meant that law students were no longer eligible to receive student deferments. Despite knowing that he would likely be called upon for military service, Warner applied to the law programs at Duke University, University of Chicago, and Yale University. He was accepted to all three and ultimately chose to attend Yale, which was at the time, and remains today, one of the most competitive law schools in the nation. He completed his first year of law school before receiving his draft notice.

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

Warner was inducted into the U.S. Army in June 1969. He underwent basic training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, before receiving orders to Vietnam. Even as he prepared to ship out, Warner remained fiercely opposed to the war in Southeast Asia. In a letter to a friend written shortly before leaving for Vietnam, he wrote, “I am now on my way to play my part in America’s greatest military disaster.”

Specialist 4 Warner arrived in Vietnam for his one-year tour of duty on 23 March 1970 and was assigned to the Public Information Office at Headquarters, U.S. Army Vietnam, in Long Binh. The massive Long Binh Post was considered one of the safest areas in all of South Vietnam and Warner’s assignment as an information specialist was considered a very safe and enviable position among troops serving in Vietnam. The Public Information Office was responsible for compiling information taken in daily from satellite offices around the country. This information was then sent up the chain of command for approval and released to the press. It was through this office that media outlets and, in turn, the American public, received much of their news about the war in Vietnam.

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

When Warner arrived at the Public Information Office, he joined a team of twelve soldiers. In one of his early letters home he explained to his parents that “it really only takes 3 guys to put out the daily press rag.” Instead of sitting around the office with little work to do, Warner and the other information specialists became roving reporters, sent out to document the war by writing articles and taking photographs for Stars and Stripes and other military publications.

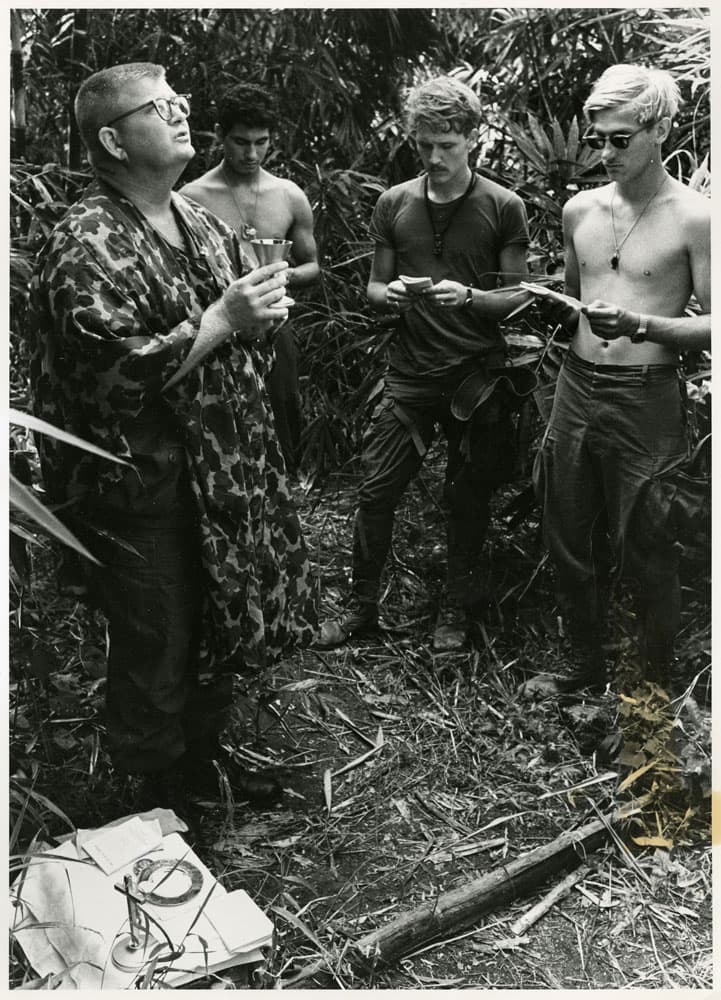

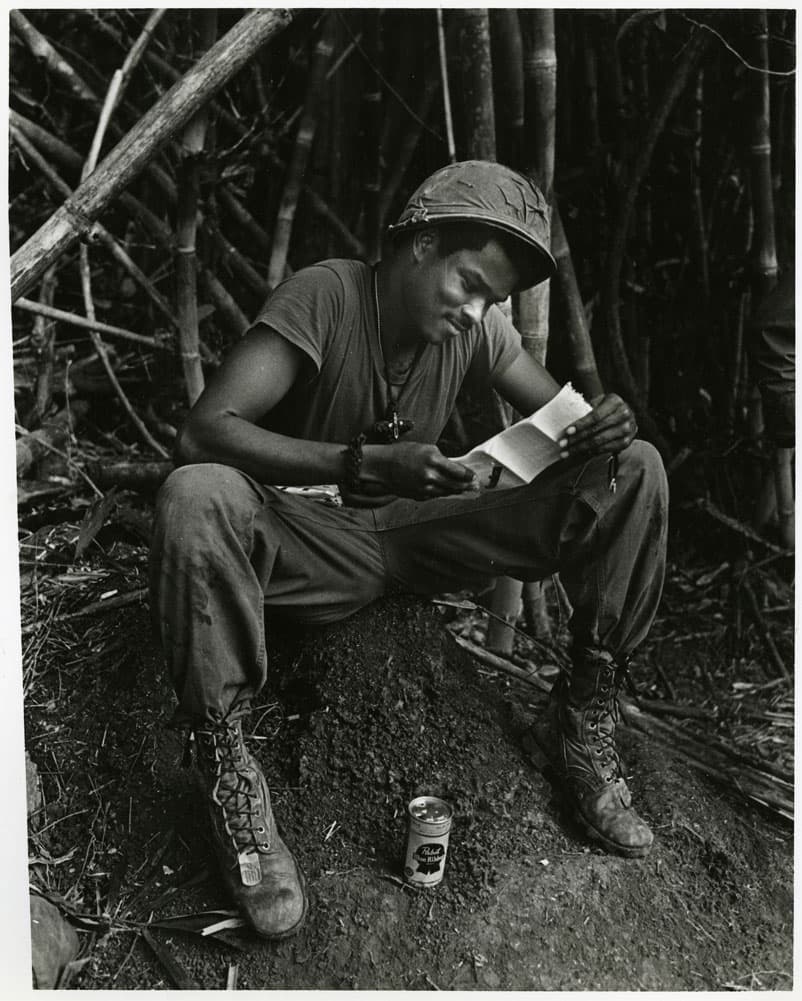

Warner could have spent his tour in Vietnam in the relative safety and comfort of Long Binh and returned home without experiencing the worst aspects of life during wartime. It is clear, however, that he was not interested in going to Vietnam and returning home without fully experiencing the war. He repeatedly volunteered to leave Long Binh to learn as much as possible about the war in an effort to experience and document the stories of the men serving in the field. He spent weeks in the jungles and rice paddies with various units, rejecting the comforts of Long Binh and embracing the harsh realities of life as a grunt.

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

Shortly after making his forays into the field, Warner began writing in a series of notebooks that served as an informal journal. He wrote often about his experiences and his thoughts about the war and his place in it. He also wrote often to his family back home in New Jersey:

“I’m confused. Mr. Nixon says the college kids are bums and that the GIs in Nam are the greatest boys in the world. Where does that leave me, a college protester now serving as a GI in Nam.”

–Notebook, 3 May 1970

“It is really kind of hard to think of stuff to write about when I’m here at Long Binh, just putting in a regular day at the office. Lots better when I’m out traveling. Boy is that fun...Talking to people, learning, learning, and learning. Ignoring my original objections to coming over here (which I still think are valid, but all history now), I wouldn’t give up what I’m doing now for the world.”

–Letter, 11 May 1970

“How the hell can you write about something like this without participating? You can’t.”

–Letter, 26 November 1970

It becomes clear as one reads Warner’s notebooks and letters that he developed a deep respect and appreciation for the men he met and served alongside. In January 1971, after ten months in the field, he wrote:

“How can one get nostalgic about Nam? I don’t know but I have. Do you know what it’s like to be in the field with a dozen others and to know death could be in every next step. The cost of admission is fear, but the price almost seems worthwhile – for in the bargain you get brotherhood, yes brotherhood, you’re so close – close like two five year-olds are close out alone in the dark. Somehow knowing you’d do things for the other guy that you’d never do anywhere else. For me, it’s knowing that if I am to die, I can’t ask more than that it be among a bunch of grunts. Why? Because grunts are the ultimate in humanness. And so you ask me how I can be an optimist about humanity, well it’s because I’ve walked with Johnny and Joe and I’ve laid my life in their hands and been richer for the experience.”

(Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College)

On 8 February 1971, Warner wrote his last letter home to his family. He downplayed the danger that he was putting himself in by repeatedly going out in the field. This was especially true along the DMZ, an area that saw frequent contact with the NVA. He also repeated a sentiment that appeared in some form in all of his letters home: that he was safe and his family, and especially his mother, should not worry about him:

“I’ve changed plans again. I just happened to be up along the DMZ when this big push west began last week and being bored I decided to go along for the ride. Don’t worry about me. I’m having a ball and believe it or not the stuff I’m involved in really isn’t that dangerous.”

On 14 February 1971, Warner was riding in an M113 armored personnel carrier while accompanying soldiers from Company A, 7th Engineer Battalion, when the convoy he was riding with was attacked by NVA soldiers. A rocket-propelled grenade struck the vehicle and exploded, killing Warner and four other GIs. He died one week before his twenty-fifth birthday and two weeks before he was scheduled to return home. He was buried at Princeton Cemetery in New Jersey.

In his will, Warner requested that his writings and photographs be donated to Gettysburg College. This documentation offers a unique glimpse into the life of an antiwar protester who went to war and lost his life while serving. Warner’s photographs have been exhibited at a number of places, most notably the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, in the early 1990s. Recently, Warner’s photographs were being shown at the New Jersey Vietnam Era Museum in Holmdel. (The exhibit, As You Were: Stephen Warner—Words and Images from the Vietnam War, was to run from 7 January to 27 June 2020, but due to Covid-19, the New Jersey Vietnam Era Museum was forced to close in March. It is hoped the exhibit will be extended when the museum reopens.)

Access the Stephen H. Warner Collection online.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 edition of On Point: The Journal of Army History and has been reproduced here with permission from The Army Historical Foundation.

By Greg Waters

Photos courtesy of Stephen H. Warner Collection, Special Collections & College Archives, Gettysburg College

Posted: 11/11/20