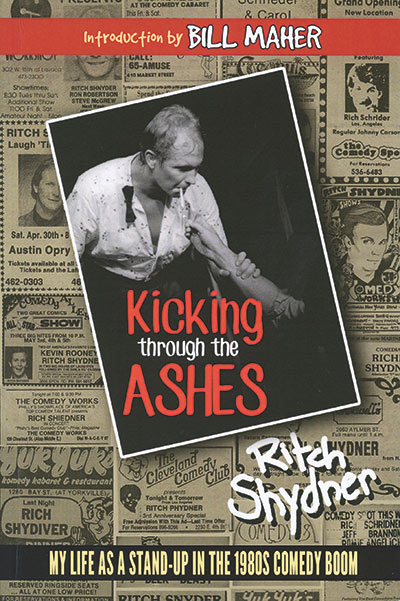

In his new book, Kicking through the Ashes: My Life as a Stand-Up in the 1980s Comedy Boom, Ritch Shydner ’74 shakes out his memories to provide his historical and personal account as a survivor and observer of the 1980s comedy scene.

In his new book, Kicking through the Ashes: My Life as a Stand-Up in the 1980s Comedy Boom, Ritch Shydner ’74 shakes out his memories to provide his historical and personal account as a survivor and observer of the 1980s comedy scene.

AN EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 1

“Don’t want nothin’ that anybody can touch”

In the spring of 1972, my sophomore year at Gettysburg College was looking like its last when Dave “Tiny” Weeks suggested I take Public Speaking 101. Professor Harry Bolich never gave less than a B for anyone who attended class. Most classmates were reciting excerpts from novels or articles from Sports Illustrated, but I did a deadpan reading of the lyrics from “Changes,” a David Bowie song. I didn’t know my serious reading with a blank expression was a form of comedy, but it got the laughs I secretly desired. As we left the class Professor Bolich pulled me aside and asked, “Can you do that again?” That was all the encouragement I needed. I spent more time on the next assignment than all my other courses to date in reworking the lyrics to the Rolling Stones song “Sympathy for the Devil” into “Sympathy for the Salesman.” It wasn’t a roomful of strangers, but for the first time I wrote something and performed it with the intent to get laughs, and succeeded. “You’re funny,” Professor Bolich said. That was important. I had heard “crazy” and “nuts” before, but never “funny.”

Nothing made me happier than making people laugh, but I knew of no way to take it any further. I played my George Carlin albums endlessly and watched every comic I could on TV, but never considered what they did as a possibility for me. Show business was just words in a song. I had no concept of how it worked, knew of no one who did. My people worked jobs at factories and offices. Those were my two options, and both seemed beyond me, feeling too blue collar for a white-collar career and too white collar for a blue-collar trade. As graduation approached, all my friends landed jobs and prepared to start their careers. I never went for an interview and left college with no more of a plan for my life than when I arrived four years earlier.

AN EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 77

AN EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 77

“Let me play among the stars”

From 1984 to 1991, I was on The Tonight Show about a dozen times. Even after getting to panel on my fourth appearance I wasn’t a lock to be called to the couch. That was okay. I wanted his approval but never felt as comfortable with Johnny Carson as I did with David Letterman. This was strictly my problem. Plenty of comics my age rolled with Johnny, but to me he was a father figure. Growing up, my dad and I had an adversarial and sometimes violent relationship. Later he felt my choice of a career in comedy was a mistake. I just couldn’t get loose with Johnny.

My dad saw me perform a few times early in my career and never had anything to say. One night, I did the whole show about him and he left without saying a word. He never called after any of my Tonight Show shots. The only thing he ever said about my chosen profession was, “What you do is tough. If they don’t buy the insurance I sell, I can say they didn’t like that insurance, but if they don’t laugh, they didn’t buy you.” Not really a ringing endorsement, but in my family, acknowledging your existence was as close as you might ever get to a compliment.

I got sober in 1985 and made amends to my dad for a lot of things, including wrecking his cars, the fistfights, and shooting at him while hunting. Three years later he got sober and came to California to clean up his side of the street. Afterward, we hugged and cried, but there remained a gap between us.

During a 1989 Tonight Show appearance, I was told right before walking onto the soundstage that there wasn’t enough time for panel. I tossed the disappointment and did my job. Feeling loose, I walked out and did a quick gunfighter pose before I started my set. It’s something I did in the clubs from time to time. Three people might get it, but that was fine. I guess it was my version of Don Rickles’ metaphor of the stand-up comic as bullfighter. The gunfighter, confrontational and suspicious, covered my relationship with the audience and the world at large.

After finishing my set, instead of acknowledging Johnny and walking for the curtain, I did a little more of the gunfighter. I pulled my jacket back with my right hand, assumed a gunfighter stance and backed slowly to the curtain, while scanning the audience for trouble.

A baffled Ed McMahon asked Johnny, “What’s he doing?” Johnny laughed. He said, “He’s doing a gunfighter.” The next day my dad called me. “That gunfighter thing you did really cracked Johnny up. You know what? You’re really good at this.”

No call ever meant more to me. There’s this old southern expression, “You’re not a man until your daddy says you’re one.” When I was young, I saw my dad making people laugh and my friends even said he was funny, but I didn’t get it. He closed the gap that night.

We’ve been laughing together ever since.