Do microplastics in the ocean affect mussels? That’s the question Hannah Collins ’16 seeks to answer through her graduate research at the University of Connecticut at Avery Point, an endeavor deeply informed by her time at Gettysburg College.

“Gettysburg’s emphasis on a well-rounded education helped prepare me for my future, as did my ability to work closely with professors on research projects,” says Collins. “Those experiences helped me realize that I really love research, particularly research with animals, and that it could be a career path for me moving forward.”

Now in her second year of graduate school, Collins does research on the physiology of mussels, clams, and oysters and how these bivalves interact with their environments. More specifically, she’s interested in how microplastics—particles smaller than five millimeters—impact bivalves’ microbiomes, and she’s currently focusing on mussels.

“Microplastics and plastics in general are copious in our oceans and waterways. Microplastics are so small that you can’t see most of them with the naked eye. Many of them are roughly the same size as the food that bivalves are eating,” she explains. “Mussels are suspension feeders and filter particles out of the water. Because of the way they feed, the thought is that they would be particularly susceptible to ingesting microplastics.”

Collins’ research investigates if microplastics are having a harmful effect on muscles’ microbiomes, which are the resident bacterial communities in their guts that aid health and immune function. “We are learning more and more about how beneficial the gut microbiome is for all living things,” she says.

In many ways, this scholarship began percolating while Collins pursued a double major in biology and psychology at Gettysburg and did hands-on research with professors here. During her senior year, she assisted biology Prof. Michael Caldwell with his research on red-eyed tree frogs. She watched behavioral video footage of frogs that Caldwell had filmed in Panama and tracked the frequency of their different behaviors and how long they lasted. Earlier on in her undergraduate career, she worked with her advisor, biology Department Chair Prof. Matthew Kittelberger, to help track and analyze the neural responses of fish. Little did Collins know her future would take her to a salmon fishery in remote Alaska where that experience would come in handy.

These deep research experiences served Collins well after graduation when she took a temporary, six-month position with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) doing freshwater mussel surveys, a job that was premonitory in terms of her relationship to studying bivalves. “I surveyed areas of the Delaware River, counting how many and what types of mussels were present to get a sense of the health of the river,” she explains. After her work with the USGS, she applied to and was offered a position at a non-profit Alaskan salmon hatchery.

“After my work on the Delaware River, I was looking for another position and nothing was really panning out except this offer in Alaska! I’d never been to Alaska, and it wasn’t really a research position; it was a technician role. I was nervous, but my parents said, ‘You can do anything for a few months’,” she laughs.

And she did, for more than a few months. Beginning work in the bitter cold of February, Collins collected salmon eggs, fertilized them, incubated them through the winter and spring, raised the babies for two to three months on fish food, and then released them back into the wild in order to help sustain salmon populations. She worked in Alaska for two years. Collins enjoyed seeing how the science she learned in Gettysburg classrooms and research labs “played out in the real world” and the experience confirmed that she wanted to pursue the oceanography side of biology, leading to her enrollment in the MA program at UConn and her current research. She considers her time in Alaska a formative one and encourages everyone to do something outside their comfort zone.

“I can't emphasize enough how much that mindset of ‘you can do anything for a few months’ has served me well by taking me out of my comfort zone and exposing me to new, exciting opportunities. My advice to Gettysburg students is to push yourself. Take courses that intimidate you. Sometimes being scared is a really good thing. If you don’t let it stop you, it can drive your path and reveal your interests,” she says.

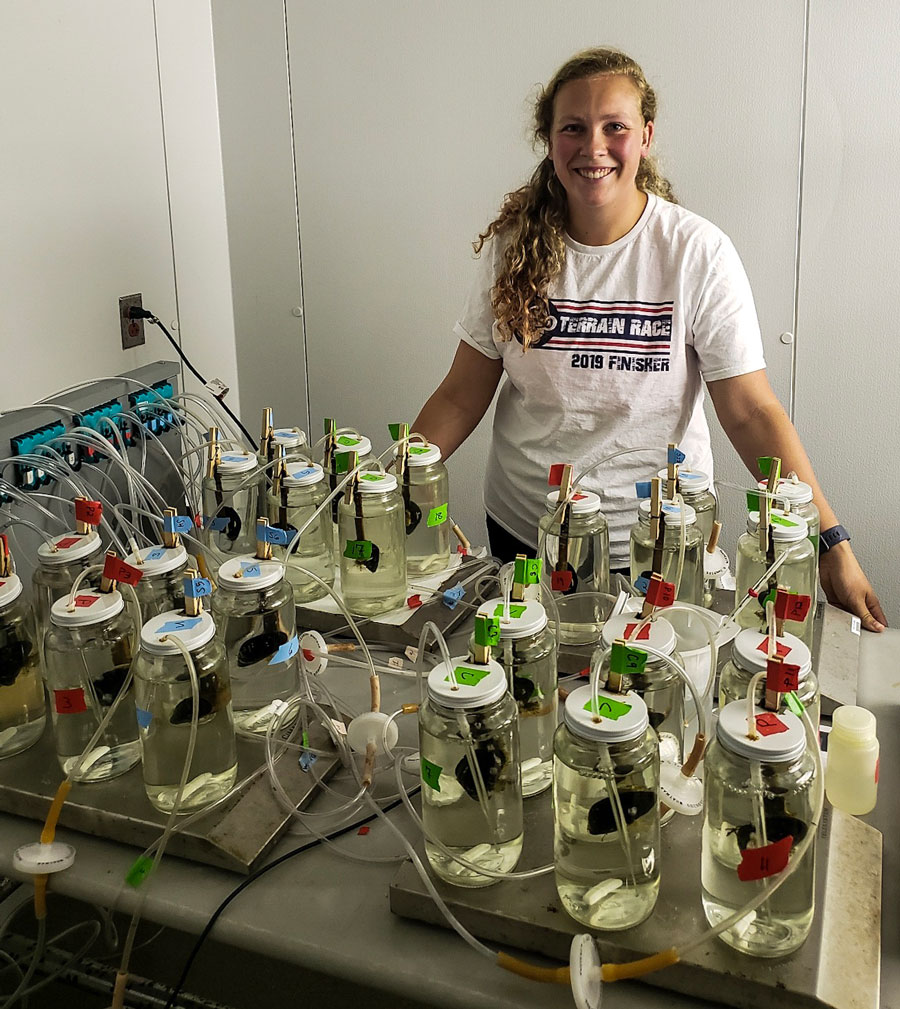

Currently, in her laboratory at UConn, Collins is conducting experiments on her most pressing interest. She soaks microplastics in seawater for two to three days to develop a biofilm and then exposes mussels to these microplastics alongside the algae they eat. After about three weeks, she removes the mussels and determines the bacterial community of their gut microbiomes, as well as the surrounding tissue structures, to see if there are any changes compared to mussels that were not exposed to microplastics.

She explains, “When microplastics float around in the water for a while, they develop a biofilm, which is a coating of bacteria and microorganisms. My research seeks to find if ingesting biofilm—which could expose mussels to foreign bacterial species that are not usually in their system, or to potentially harmful bacterial species—is having a negative effect on the mussels and whether that could be detrimental to the humans who consume them.”

Thus far, she’s not seeing any impacts.

“There’s some evidence to suggest that mussels may have the ability to control certain aspects of their microbiomes, which may allow them to limit the effects of the biofilm on microplastics, but there’s still a lot of work to be done,” she says. “Nevertheless, it’s interesting working on this part of the plastics problem because we definitely, as a global society, need to reduce our plastic consumption and stop plastic from getting in our oceans. But the evidence is showing, at least when it comes to marine bivalves and human health, there's not a whole lot of risk.”

Collins expects to complete her master’s degree in the spring and will continue her research at UConn as a doctoral student. She says, “Ultimately, I’d like to use scientific research to drive positive environmental policy changes at the government level.”

Learn more about student-faculty research opportunities at Gettysburg College.

By Katelyn Silva

Photos courtesy of Hannah Collins ‘16

Posted: 02/04/21