A New York City public park, unusually devoid of people, but in full bloom. A home office, made complete with Zoom avatars, that still offers connection. A home dining room turned restaurant, thanks to a dinner delivered to the doorstep with a small bouquet of flowers.

Each of these spaces shapes an experience, one that may have looked different prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but also one that has magnified the value of human connection. With many people working from home, the new-look work and home environments have caused all industries to rethink their interactions with society.

“In my First-Year Seminar, ‘Work, Society, and Self,’ we examine how work and occupations have changed over time, especially how that change relates to technology and societal changes,” said Management Lecturer Bennett Bruce. “We also … examin[e] how our occupations affect our sense of self and identity. For better or worse, our occupation, work, and even work environment play a significant role in how we develop our sense of self and identity. It shapes how we see ourselves.”

As the pandemic evolved, each industry adapted, adjusting to a variety of new factors including new revenue streams and customer preferences.

“Businesses that rely on in-person contact, like restaurants, bars, travel, or entertainment, have been hit hard,” Bruce added.

Gettysburg College alumni especially—spanning industries and the globe—sought out those connections to keep their businesses afloat. With creativity and hope, that desired human energy was preserved in unexpected and reimagined spaces.

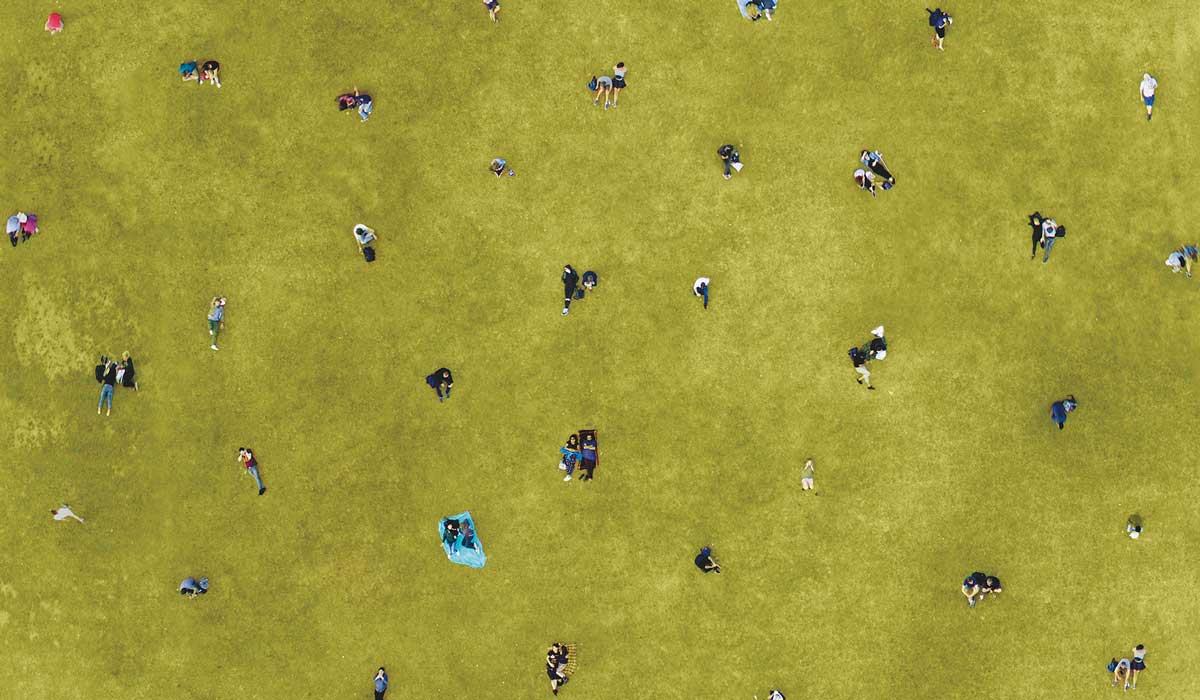

Walks in the park

During the pandemic, BJ Jones ’94, president and CEO of Battery Park City Authority in New York City, received moving notes from residents about their park experiences. One in particular, he said, was unforgettable: “Now with the quarantine, daily walks are more cherished. Leaving the isolation of my apartment and walking through the parks is uplifting. It is reassuring to see everything so clean and in spectacular bloom.”

“I saw people’s feelings about space evolve, as did my own,” Jones said. “I made it a point to take daily walks in our parks during lockdown and have kept it up since. At first, it was out of a sense of duty, but it quickly became a necessary practice for my own peace of mind.”

Finding beauty in unlikely places inspired Jones and his team to “think differently about connection” as they found new ways to engage the staff and the community, planning virtual activities online and physically distanced events in their parks, including a Poetry Path, new public art installations, and music and dance performances.

“We’re social creatures,” Jones added. “It’s vital to our well-being. Each person will figure it out in their own time. … But I see it already happening. I pass by people having reunions on the sidewalk, hugging after not seeing one another in months. The weather was perfect recently and so many people were out celebrating like it was New Year’s Eve—but it was just a Tuesday.”

Connections a la carte

When Danielle Billera ’87, a managing partner of SUGARCANE raw bar grill and founder of SUSHISAMBA and Duck & Waffle global brands, had to transform her brick-and-mortar restaurants into delivery hubs while she was quarantined in New York, she knew that delivering the meal itself was not enough.

Billera described how her “human-connecting industry” couldn’t truly go remote. Each host, server, and chef form bonds with customers through personal interaction, in a space where all five human senses are activated.

“This confirms you are alive—it puts you as an individual on fire,” Billera said. “Nothing can take the place of an in-person restaurant experience, as none of this can be achieved through Zoom.”

Without the shared space, Billera and her team had to send the experience home.

“The delivery bag was filled with good food but was void of the energy of the shared experience,” Billera said. “We added a small bouquet of flowers to each delivery order—colorful, beautiful, and alive—a nod to what we were missing and what we would strive to get back.”

Red carpet, reimagined

For Cynthia Hill ’90, who has built her career in Southern California’s entertainment industry, memories instantly flow back each time she steps foot on campus. Even though the College Union Building looks different now than she remembers, the experiences she had with her friends in that space will be cherished forever.

“Your memories are tied to spaces,” Hill said. “Our memories are not tied to that time we Zoomed. Our memories are tied to shared experiences in person.”

On April 25, Hill’s brand partnership and sponsorship agency, zakHill, where she is a principal, was tasked with coordinating the Oscars’ production of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award to the Motion Picture and Television Fund at Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre with a remote component.

“Typically, we produce the fan component of the red carpet—however, this was not the year to have fans,” said Hill, who has worked the Oscars the past seven years and reunited her team in person to produce the virtual event. “These are people whom we usually see once a year. It’s a whole group that comes back together to work the Oscars, and you wanted a hug. You want to be normal, but yet you knew you couldn’t.”

She likened the first in-person meeting—masked and distanced—to flexing a muscle that she hadn’t in a while: “We all talked about how we all are really desperate to go back to that camaraderie you had in the office, as we like seeing people and having that sense of connection.”

Just as Hill helped shape the red-carpet experience, the reverse, she said, is also true: “I do think our spaces shape us.”

The show must go on

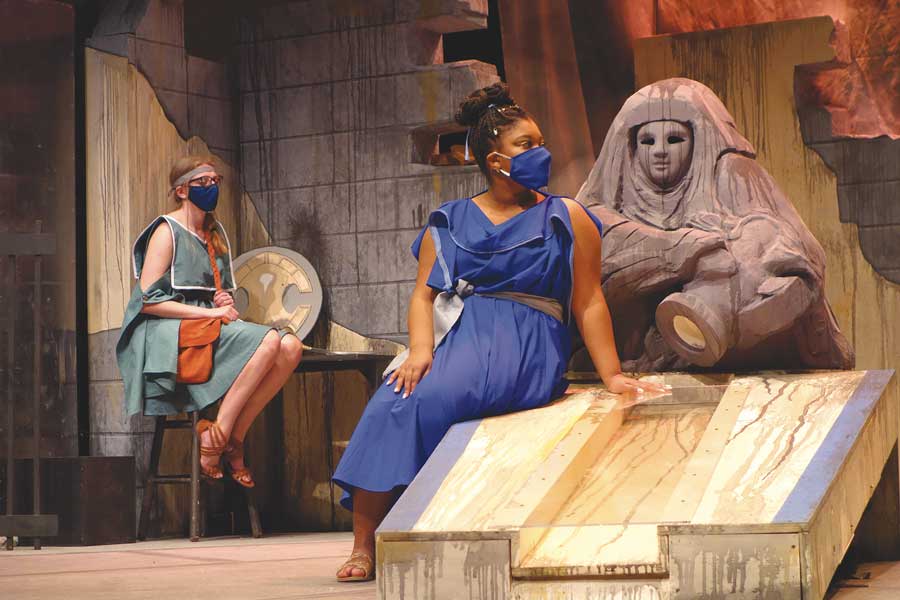

According to Weston Jackson ’14, who directed Antigone Now in Kline Theatre in March 2021, the theatre industry has had to rely on the power of emotion now more than ever. The stage is an outlet to express oneself, he said.

When the pandemic hit, he lost his job as a high school teacher because its performing arts program was cut. His students lost a creative outlet. Broadway lost its live shows, and theatre-makers lost their livelihoods.

The industry, and Jackson, were forced to change courses. They leaned into virtual performances, making the theater more accessible and affordable on alternative viewing platforms.

“It’s been a time for theaters to [reflect:] … ‘How can we do better when we do come back? How can we be a better theatre community, be a force for good in our community when we are up and running, and get more people into the theater than were even here before?’”

“Honestly, I kind of hope we don’t get back to normal,” Jackson said. “Don’t get me wrong, I want to be in a crowded theater. On the flip side, it’s going back to what’s really important. If we, as a theatre industry, want to get bigger and better, you have to expand that access, so I hope we don’t go back to closing the gates to people. I want to keep what we’ve changed for the better.”

Take me out to the crowd

Rob Blomberg ’76, a Liberty Mutual Insurance retiree and Red Sox season ticket holder turned Fenway Park tour guide, would usually lead tours up to 100 people in pre-pandemic times. Since 2015, he’s given tours of the iconic stadium to visitors from Nepal and Tibet, rival team fans, and President Emerita Janet Morgan Riggs ’77, who visited during a 2016 Gettysburg Great event.

When COVID-19 hit, he missed the interpersonal contact. Last year, tours ceased altogether, but Blomberg is now able to give tours to groups of 50 people.

“I’m looking forward to the time when I’m doing a tour without a mask, and you can really read people’s faces to see whether or not you’re connecting,” said Blomberg.

Fenway Park has roughly 38,000 seats, but only 12 percent were open in April 2021. That number jumped to 25 percent on May 10, 2021. The remaining seats were zip-tied. In July 2020, fans could not attend, and the Red Sox piped in fake crowd noise to simulate cheering. While 25 percent of the seats were opened for fans in May, it’s not nearly close to the beloved Red Sox community once known as a tourist attraction in Boston.

Similar to a ribbon-cutting of a new space, Blomberg anxiously awaited a ceremonial zip-tie clipping.

In July 2020, fans could not attend, and the Red Sox piped in fake crowd noise to simulate cheering.

“I would love to be working at Fenway the day we remove the rest of the zip ties. You know, we laugh about it, but it shows progress, and I think for many people, progress is what they really need. It’s a wild feeling. It’s like a real feeling of relief.”

That day came on June 8, 2021. All zip ties were removed and full capacity was restored. Masks are now optional.

“Now that’s real progress,” Blomberg exclaimed.

Is that feeling of relief here to stay? What changes to spaces are for the better? What will be accepted, and what will be set aside? If anything’s certain, a newfound appreciation for shared spaces—the “new sense of euphoria,” as Jones described it—and the human connections that are forged within them, will be carried onward.

How have your shared spaces changed, and how have you adapted in response? Share your story by emailing alumnimagazine@gettysburg.edu.

by Megan Miller

Posted: 08/31/21