I have been interested in wine since I was young—too young, in fact, to consume it myself. Later, as a history major at Gettysburg, I learned the methodologies of historical analysis that would eventually translate to my career as a Sommelier: I now have a valuable skill to use to explain the intricacies of wine, and to do it against a historical backdrop.

So, what does make a great wine? As a Sommelier, I get asked this question on an almost daily basis. To answer it, let’s first get back to the root—literally.

Strong roots and a solid foundation

Wine is unlike most other agricultural products in the world in that the worse the soil, the better the end product. Sommeliers who study soils have found that fertile soils enable a grapevine to produce abundant fruit, which dilutes the concentration of fructose and diminishes the end flavor of the wine.

This study of soils, or “terroir,” isn’t a new undertaking. Beginning in the 10th century, Benedictine monks in Burgundy’s Cluny Abbey studied grape development across vineyards devoted to communion wine. They found that marl, an amalgamated soil, creates tremendous concentration in Chardonnay, while the finicky Pinot Noir thrives on quick-draining limestone. Their study of soil’s impact on wine has influenced winemaking around the world.

Caretaking and stewardship

From the pruning of grapevines to the use or disuse of pesticides (look into organic and biodynamic wines), the treatment of the vine during cultivation is important to the end result of wine.

Skin contact

Contrary to common belief, a red wine isn’t red because of the color of the grape’s juice. Every grape in major commercial production today, in fact, has white juice. Creating red wine requires leaving pressed juice in contact with grape skins for an extended period of time—a process called maceration. Want to make a rosé? Simply shorten maceration time.

Patience and control

The fermentation process takes time. In standard fermentation, yeasts—either wild or cultivated—are introduced into the pressed juice of harvested grapes. Those yeasts break down sugars, releasing carbon dioxide and alcohol, along with heat. Many modern winemakers use temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks, ensuring that released heat doesn’t kill yeasts. At 15 percent alcohol, most yeasts will die naturally as their environment becomes toxic.

To produce sparkling wine, a sealed bottle of wine is subjected to a secondary fermentation whereby carbon dioxide isn’t released into the air, but is instead contained and reabsorbed into the wine. This process is most common in Champagne, where the absorbed carbon dioxide is released as bubbles!

The finish

While the average bottle of Barefoot or Woodbridge can be $5, a bottle of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti’s 1945 Romanée-Conti Grand Cru sold at auction for $558,000 in 2018. How does something that is essentially grape juice end up costing the same as a Ferrari, and how does that price reflect the taste? In the end, a “great wine” is in the eye of the beholder (or taster!) and it’s a sommelier’s job to guide you to find the wine you’ll like best.

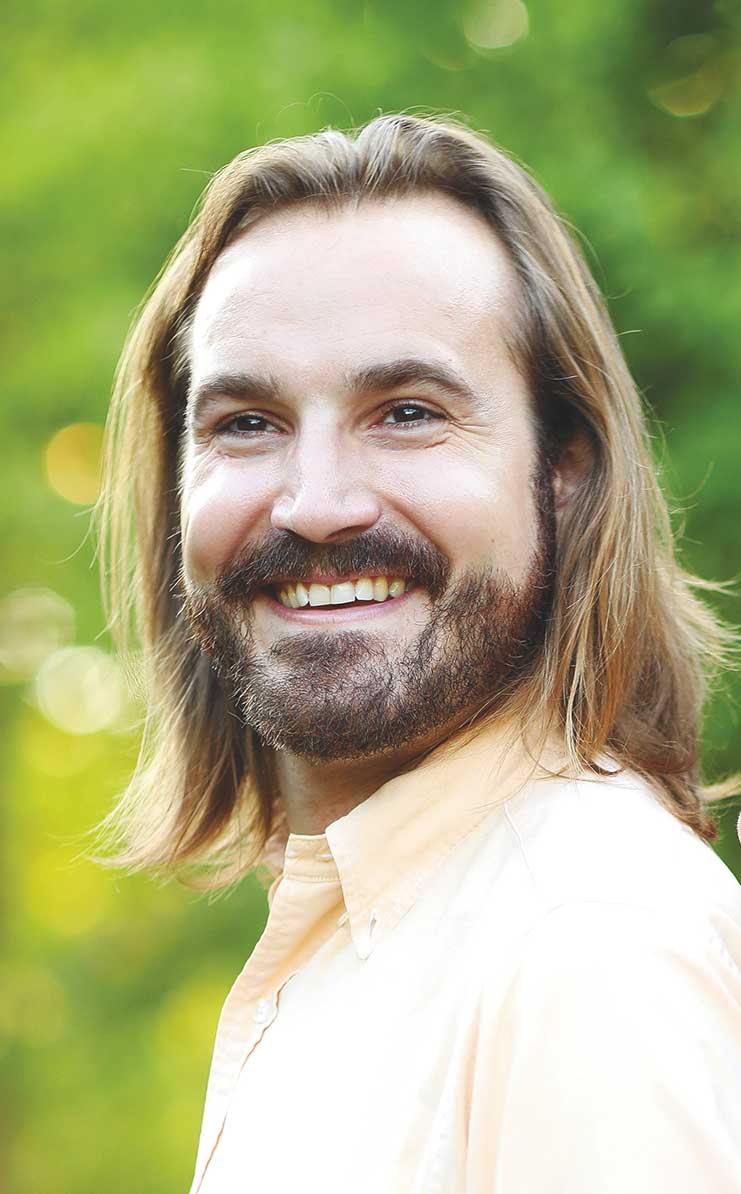

Story by and photos courtesy of Alexander Lopez-Wilson ’10, Certified Specialist of Wine (CSW) and French Wine Scholar (FWS)

Posted: 08/31/21