For both novices and long-time scholars of the Civil War, the sheer size of Civil War armies and engagements can all too easily reduce soldiers to mere statistics or red and blue blocks on a battlefield “chess board.” Their individual stories, humanity, diverse backgrounds, and perceptions of battle become lumped into often monolithic characterizations of “Union soldiers” and “Confederate soldiers.”

However, for student contributors to the Killed at Gettysburg project, including Erica Uszak ’22 and Ryan Bilger ’19, unpacking the layered experiences and legacies of individual soldiers who fell at Gettysburg has provided an entirely new lens to understand both the unifying threads that bound Civil War armies together, as well as the unique, human nuances of soldiers’ life stories and experiences that shaped the wide-ranging meaning and impact of this seminal battle.

“Their stories, their family and friends, [and] their hopes and dreams all made up the bigger picture of their lives, and my Killed at Gettysburg projects ensured that I did not lose sight of that,” said Bilger, who authored four soldier profiles as a student fellow at the Civil War Institute (CWI).

Uszak, who authored two soldier profiles, likewise developed an unexpectedly deep sense of personal empathy for her historical subjects.

“Although the soldiers that I researched, Octave Marcell and Elijah Hayden, lived through a much different time, as I dug deeper into the project, I felt myself growing to know and relate to them,” Uszak reflected.

Launched in the spring of 2017 and now led by Civil War Institute Assistant Director Ashley Whitehead Luskey, the Killed at Gettysburg digital history project spotlights a cross-section of the more than 7,000 Union and Confederate soldiers who died at, or shortly after, the Battle of Gettysburg. It not only deepens students’ knowledge of the Civil War era and its significance within our national narrative, but also hones their research, writing, and critical thinking skills.

Researched and written by Gettysburg College students from the Institute’s Fellows program, as well as by a small cadre of first-year student volunteers, these profiles tell the stories of Gettysburg’s fallen soldiers, including their motivations for enlisting, their war-time experiences, and the wide-ranging impacts of their deaths, both in history and in memory. They also trace the soldiers’ final footsteps across the Gettysburg battlefield using digital mapping, student-captured photographs of pertinent landmarks, and short interpretive captions.

This research and production process teaches students the ability to understand deep historical context—from shared worldviews that bound soldiers from diverse backgrounds together to how the war changed them over time—and prepare it for public consumption. They learn how to bring cohesion to military history while cautioning against comprehensive statements about any one group of soldiers. They also learn how to think broadly and historically as budding historians and civically informed scholars.

“Their duty to their country and family, their principles, and their courage impressed me,” said Uszak, upon discovering the soldiers she was researching came from poverty and sacrificed everything to defend their country. “Their perspectives offered me a much more personal view of the war and what it meant to be a Union soldier.”

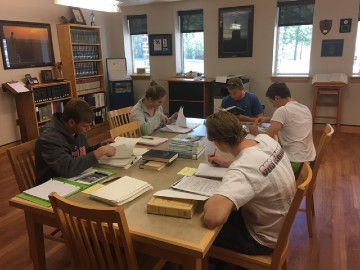

As part of the Killed at Gettysburg project, students travel to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., to cull through the Compiled Military Service Records and widows’ pensions of their chosen soldier. They also visit the Gettysburg National Military Park library to peruse the regimental files of their soldiers’ respective regiments. Both experiences bolster their historical interpretation skills and lead to intellectual discoveries.

Bilger, who interned at several Civil War battlefields, such as Antietam and Manassas, and recently graduated with a master’s degree in history and public history from West Virginia University in May 2021, credited these trips, and specifically learning the ArcGIS digital mapping programs, for his development as a public historian.

Uszak, who interned and served as a seasonal park ranger at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, and also hopes to pursue graduate school and a career in public history, created a unique connection through her research. It led her directly to her soldier’s great-great-grandson, who provided additional materials to supplement her project and then was “overwhelmed with emotion” to see the final product.

In addition to connecting with their subjects, students connect with each other through group readings and discussions, sharing their soldiers’ stories within the context of foundational articles and books about the Civil War and 19th-century America. Together, they explore a wide range of Civil War era topics, including gender, religion, class, immigration and ethnicity, cowardice and courage, and more. Analyzing a diverse group of soldiers, they are able to interpret how the war transformed soldiers’ and civilians’ relationships with each other, their communities, and the government. Additionally, the Killed at Gettysburg project helps students and the general public understand the roots and evolution of Civil War memory.

“Students not only whet their appetites for further, more in-depth historical research, but learn a humbling lesson about the continuous conversations and on-going debates that are at the root of doing good history,” said Luskey. “For the students, as well as for their readers—whether they’ve been to Gettysburg 100 times or will never have the chance to go—these profiles, and the true cacophony of voices and discourses they represent, present a vivid and compelling, impressionistic painting of not only the rank and file here at Gettysburg, but also of life in Civil War America.”