For the last 20 years, Gettysburg College honorary alumnus Rev. Karl Mattson has called two acres of the Gettysburg Battlefield home.

Looking out the window of his study, he bears witness to the land on which the first day of the battle was fought. Beyond his front windows, countless cars pass by every day—following the battlefield’s auto tour route. And purposefully pinned in his front lawn is a black and yellow sign that reads: “This battle was fought because Black Lives Matter.”

Mattson has dedicated his life to fostering, bridging, and nurturing communities. In downtown Brooklyn, he forged a ministry that brought the traditional Swedish congregation and the neighboring Hispanic community together, and years later, he pursued inner-city ministry at a large, black church in the Southside of Chicago.

In 1977, his path led him to Gettysburg, where he served as the College chaplain for 14 years and founding director of the College’s Center for Public Service for 10 additional years before retiring. During these 24 years, he also founded Project Gettysburg-León and played an instrumental role in bringing Habitat for Humanity to the College and initiating an annual celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day—leaving behind a trail of heartfelt change wherever he went.

This past July 4, when dozens of armed counter-protesters assembled on the battlefield mere miles from his home in response to rumors of a planned flag burning, he knew he couldn’t, and wouldn’t, just stand by and stay silent.

“My daughter, who teaches politics at the College of St. Mary in Omaha, Nebraska, told me, ‘You gotta do something,’” Mattson said.

Yard signs

In mid-summer, Mattson worked with his daughter to create hundreds of yard signs—one of which he proudly displays on his property.

The signs have been primarily distributed in Gettysburg, but others have made their way across the country as passersby shared photos of the signs on social media. While many were uprooted during the presidential election season, several can still be seen scattered across town alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. signs, which the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, in collaboration with local nonprofits, sold as a fundraiser during its annual MLK Celebration.

“Gettysburg is America’s most sacred place outside of Washington. Without the Battle of Gettysburg, the nation may not have been reunited, and the emancipation might not have become effective. We simply intended for the signs to begin a discussion around that issue,” Mattson said. “The phrasing, ‘This battle was fought because Black Lives Matter,’ is seldom stressed in the retelling of the battle’s history, but it’s certainly true.”

Barring a few obscenities, Mattson has received overwhelmingly positive reactions—the most touching of responses coming from a number of black families who were visiting Gettysburg and stopped to share that the signs made them feel valued, seen, and heard. In January, he and his daughter placed a new order for 50 more yard signs to be made.

“The reason we’re going to [order more] signs is because the dialogue of Black Lives Matter, on the battlefield and elsewhere, is going to continue. And we want to remind people of the lasting importance of that dialogue,” Mattson said.

He hopes that these dialogues spark larger discussions that challenge popular narratives around the Battle of Gettysburg and lead to real change. Some changes are already in motion on the battlefield, such as revisions to the interpretative wayfinding signage around the park, but Mattson said the reimagined signage is just the first step.

There’s more work to be done.

Wayfinding signs

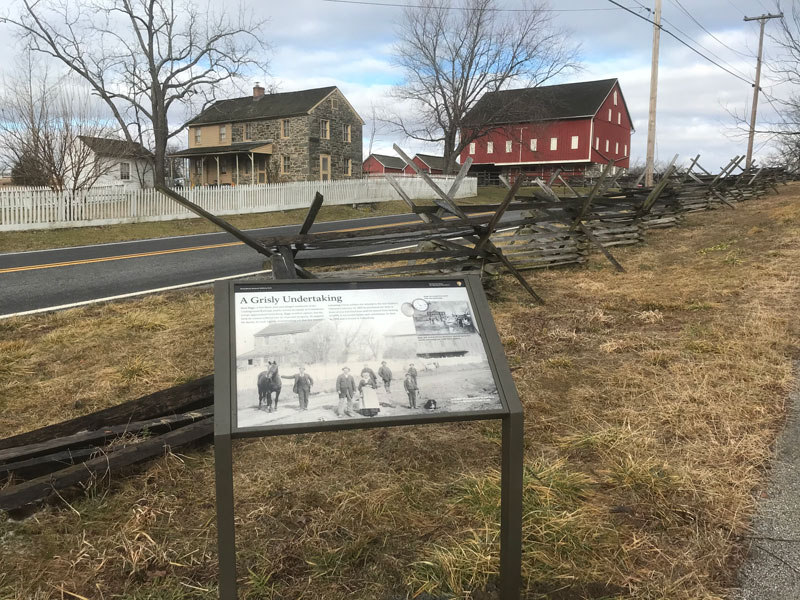

Evidenced by the passionate momentum of community members like Mattson, the historical context of the battlefield has been constantly evolving since 1863—with one of the most dynamic changes being the National Park Service’s placement and reevaluation of interpretive signage.

The first series of signs was installed in the 1930s as Gettysburg transitioned from a lived event to a remembered one, and today, for the million or so visitors who pass through each year, the signs recount and contextualize the history of the Battle of Gettysburg. They tell a story and serve as springboards for vibrant discourse.

“For the National Park Service, our interpretive signage offers an opportunity to change the narrative of what a trip to Gettysburg could be or should be,” said Christopher Gwinn ’06, who was a history major at Gettysburg College and is now Chief of Interpretation and Education at the Gettysburg National Military Park. “It means facilitating some very difficult and critical conversations with the people who come to Gettysburg about the national past, and how we can use Gettysburg as a lens through which to, if not see the future, perhaps illuminate the path forward.”

One such change is the addition of panels across the battlefield, which will tell the stories of individuals who played a significant role in the battle but over time were marginalized, including immigrants in the Union and Confederate armies and the black community in Gettysburg. Other panels will provide visitors with the historical context of how, when, and why Confederate monuments were placed—all of which are being thoughtfully crafted with help from various local historians and national scholars, including Africana Studies and History Prof. Scott Hancock.

“The momentum of anti-racist work has been building for quite some time, since the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement started in 2013 with the killing of Trayvon Martin,” Hancock said. “It’s not a new discussion, but I think the recent BLM surge has increasingly pushed people, including those at the Gettysburg National Park service, to rethink what it means if they have a battlefield where the black presence is absent, when this war was started because of slavery.”

Hancock is optimistic that, under the leadership of Gwinn and his colleagues at the Gettysburg National Military Park, the battlefield will continue to evolve in years to come—becoming the place in which he, Gwinn, Mattson, and many other passionate Gettysburgians hope for. A place where all feel welcomed, the marginalized are celebrated, and black people are placed back into the center of the story.

However, at the heart of this change, Gwinn says, is not the National Park Service, but the people.

“The National Parks aren’t owned by the National Park Service. We just take care of them. They belong to the American people. They belong to you,” he said. “And every generation—current and future—has an obligation and an opportunity to reinterpret and evolve our national landscape and the stories those places tell. Gettysburg is just one example.”

Learn how Gettysburg College is combating racism and teaching its students to embrace difference.

Those interested in purchasing a “This battle was fought because Black Lives Matter” yard sign can email Karl Mattson at kmattson@gettysburg.edu.

By Molly Foster

Photos by Shawna Sherrell, Peter Francis ’21, and Miranda Harple and courtesy of Amanda Heim, Buddy Secor, and the National Park Service.

Posted: 02/12/21