An undercurrent of history flows through every wall on the Gettysburg College campus. Founded in 1832, the campus originated in a building that still stands today—on the corner of South Washington Street and High Street.

Over time, our campus expanded and had a front row seat to America’s history. Standing in the midst of the defining Battle of Gettysburg during the Civil War, our buildings lend themselves to a curious mind: How many footsteps echoed in the same hallways? How many faces peered out of the same windows?

Each building has witnessed the ebb and flow of students, faculty, and staff. For nearly two centuries, they have taken in the challenges and celebrations of the College’s most momentous occasions, enduring with resilience and transformation.

Discover the stories of seven buildings on the Gettysburg College campus that have left a lasting mark on our history.

Pennsylvania Hall

Construction Began: April 1836

According to College Historian and History Prof. Michael J. Birkner ’72, P’10, the building that has undergone the most transformation and is still standing to this day is Pennsylvania Hall, also known as Penn Hall.

It was the first structure to be built on the land our campus exists on today and remains one of our most iconic buildings. Penn Hall serves as a focal point for our traditions, including Convocation and Commencement, and it was where campus life was centered in years past.

Penn Hall, fondly known by many as “Old Dorm,” was once a residence hall for students, an academic building with classrooms, the home of the College president, and the location for the College library and bookstore. During the Civil War, it also served as a hospital for Confederate and Union soldiers. In the 1970s, it was renovated to become an administrative office space as new residence halls were constructed across campus.

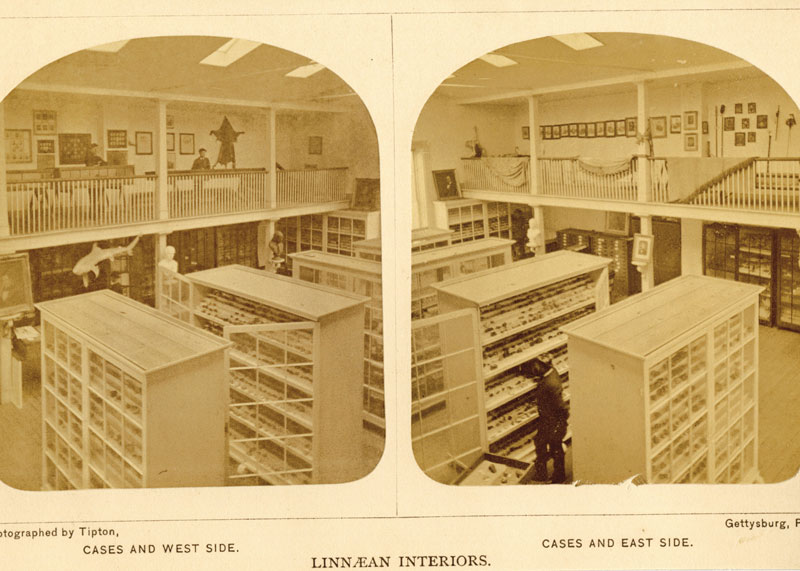

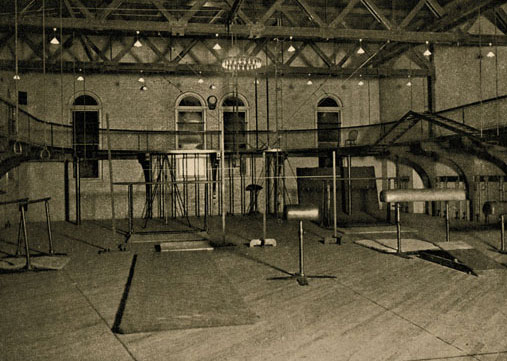

Linnean Hall

1846-1942

Although Linnean Hall is no longer on campus, its history is still discussed today. This building was designed by a faculty member named Herman Haupt, and it was partially constructed with the help of students.

“Haupt went on to fame as an engineer during the Civil War,” Birkner said. “He was someone whom President Lincoln was very pleased with because he was so helpful in terms of making it possible to get things moved by rail.”

Linnean Hall was built to be a center for scientific exploration and inquiry, including housing a mineral collection. In 1890, it was transformed into the College gymnasium until Plank Gym was built in 1927. Eventually, it became a storage facility. It was demolished in 1942 following encouragement from the student body because of its deterioration.

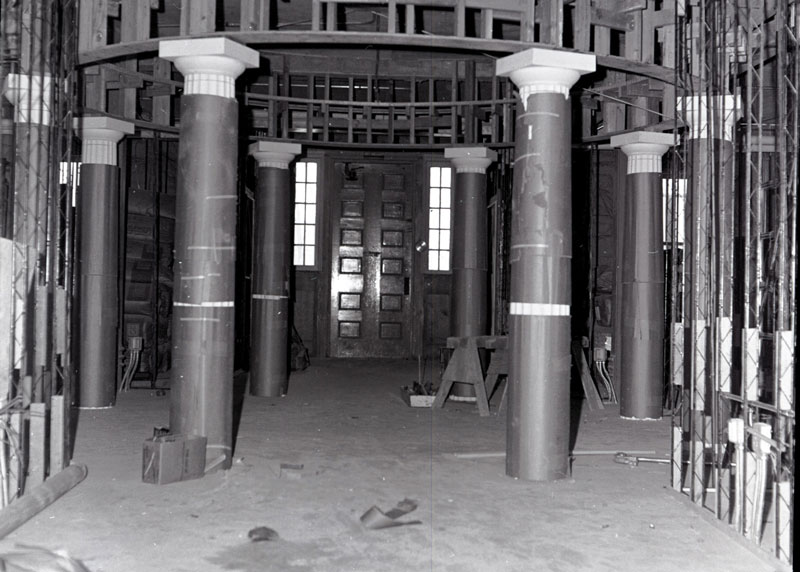

Brua Chapel

(also known as Kline Theatre)

Groundbreaking: 1888

Brua Chapel was built with donated funds from Colonel John P. Brua, who wished to memorialize his parents. He died before the chapel’s cornerstone was laid. Both Glatfelter Hall and Brua Chapel were built with stone from the same quarry.

Initially serving as the chapel and auditorium for the student body, the campus population soon outgrew Brua’s space and that purpose was discontinued when Christ Chapel opened in 1953. Undergoing several transformations, it today serves as a performance space. Elements of the chapel still remain in the woodwork, as do cherub figurines, the outline of sealed windows, and the bell tower. Brua Chapel is the chapel referred to in the College’s Alma Mater.

Glatfelter Hall

Year Built: 1888

Glatfelter Hall’s cornerstone was laid on June 27, 1888, the same day as the groundbreaking ceremony for Brua Chapel and close to the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Originally called Recitation Hall, Glatfelter Hall served as a center for classroom learning and provided opportunities for the student literary societies of the time.

“Students were able to get intellectually stimulated in the literary societies where they would have debates over whether or not the United States should be involved in a war with Spain [and] should the United States embrace women’s suffrage—those types of contemporary issues,” Birkner shared. “The literary societies were a perfect vehicle to have those discussions because they weren’t happening in class.”

In the original plans, a chapel was to be built where the back patio to Glatfelter Hall is now. However, due to a lack of funds, money was instead donated separately to build Brua Chapel. Both Brua Chapel and Glatfelter Hall share the same architect, John A. Dempwolf, who left his mark on the outside of each building.

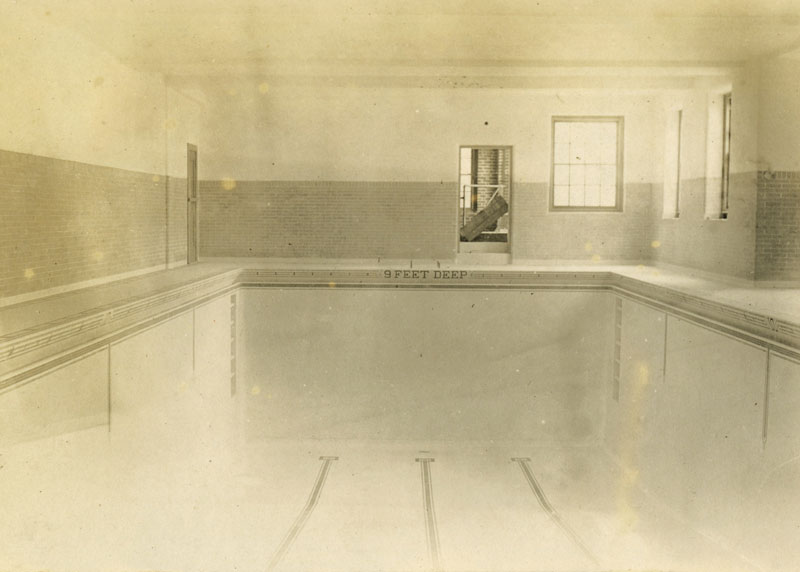

Weidensall Hall

Year Built: 1919 | Rebuilt: 1947

Weidensall Hall was built in large part thanks to the fundraising efforts of the local Women’s League and the idea of establishing a “Christian Social Hall” for students.

In 1911, the Woman’s League of Gettysburg College was formed after a meeting in Brua Chapel and comprised multiple sub-leagues in Pennsylvania. The members consisted of women who were involved in Lutheran churches throughout the region. Together, they helped raise money for a College YMCA secretary position and also contributed donations toward student activities. In 1915, the Woman’s League took on the monumental project of fundraising for Weidensall Hall.

The original plans for the building did not include the two additional side wings that stand today. After a fire in 1946 that burned a large part of Weidensall, the wings were added in the next rendition of the building.

Africana Studies & Economics Building

(339 Carlisle Street)

Year Purchased by the College: 2010

The 339 Carlisle Street structure was first built as a private residence by Colonel Charles H. Buehler, Class of 1844. Over several decades, the house held families with close ties to campus. Buehler, who served on the College’s Board of Trustees, later sold the house to J. Emory Bair in 1891. Bair served on the College’s Board of Trustees from 1896 to 1909.

Bair’s wife’s niece, Mary Catharine Kohler, Class of 1909, was raised in the home as the Bairs’ only child. Kohler later married Clyde Berger in 1919 and raised their four children in the home. In 1938, the Berger family, who owned Katalysine Springs in Gettysburg, sold bottles of the spring water outside of their house during the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. In total, members of three generations of the Berger family lived in the home and attended Gettysburg College.

In 1951, the Berger family leased 339 Carlisle Street to the Alpha Theta Chi fraternity, which became Theta Chi in 1952 and later purchased the home in 1958. The College bought the house in 2010 and renovations commenced in 2013, when it officially became the home of the Africana Studies and Economics Departments.

Huber Hall

Year Built: Circa 1916

During the late 1830s, the College established a Preparatory Department that provided boys in the local community an education for two to three years and introduced them to the campus if they wanted to move on to further studies. Over the years, the Preparatory Department was housed in various buildings on campus. Huber Hall was built in 1916 for the Preparatory Department—rebranded as the Gettysburg Academy—during President William Anthony Granville’s tenure. Initially called the Main Building, it was renamed in 1941 to Huber Hall in honor of Charles H. Huber, Class of 1892. During his time here, Huber served as the principal of the Preparatory Department, the headmaster of the Gettysburg Academy, and the director of the Women’s Division of the College.

At the time Huber Hall was built, Granville instructed the architect, George C. Baum, Class of 1893, to have all new buildings resemble a similar style as Pennsylvania Hall. Huber Hall included a dining hall on its premises.

In 1930, the Board of Trustees made the decision to bar women from a Gettysburg College education. They reversed this decision in 1935. Huber Hall was turned into a female-only residence hall, and the Gettysburg Academy was closed.

By Shawna Sherrell

Photo by Abbey Frisco

Posted: 06/01/22