Exhibition details

This exhibition was curated by Cyndy Basil, ’25, under the direction of Gallery Director Sarah Kate Gillespie, and Kolbe Summer Scholar Isobel Debenham, ’25, under the direction of Professor Felicia Else, Art History.

The show received support from the Provost’s Office, the Department of English, the Department of French, and the Program in Public History, Gettysburg College.

Click to Explore Prints from the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation

September 4 – December 14, 2024

Location

Main Gallery

Reception

Lecture

“‘Extravagant genius’? A Portrait of the Artist,” by James Clifton, Director of the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, September 18, 4pm, followed by a reception until 6pm

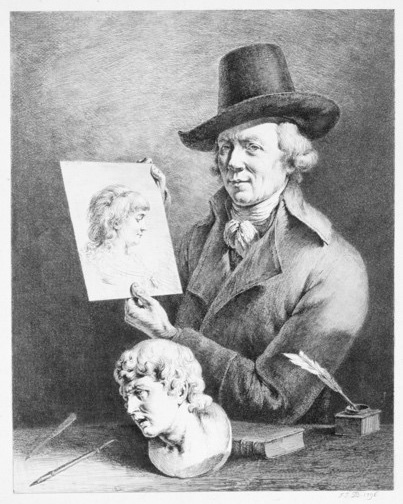

Image: Jean-Jacques de Boisseau, Self-Portrait, 1796, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Houston

Works on display

Consisting of fifty-one prints on loan from the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, this exhibition examines how artists depicted themselves and their profession from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The show includes artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Salvator Rosa, William Hogarth, Claude Lorrian, and Francisco Goya, among others. Created during a period when the social status of artists was in flux, the prints represent both artists’ lives and work, and the roles that both artists and the arts held in society. Full of allegory and rich in satire, the works include self-portraits, representations of artists at work, and exhibition and academy spaces.