Gettysburg is renowned as a place rich with history, but not everyone’s history is equally told. That’s one of the reasons why Andrew Dalton ’19, director of the Adams County Historical Society, began compiling a database to document the lives of the hundreds of black men, women, and children buried at Lincoln Cemetery in the 19th and early 20th centuries, including thirty members of the U.S. Colored Troops who were denied burial in the Gettysburg National Cemetery due to segregation.

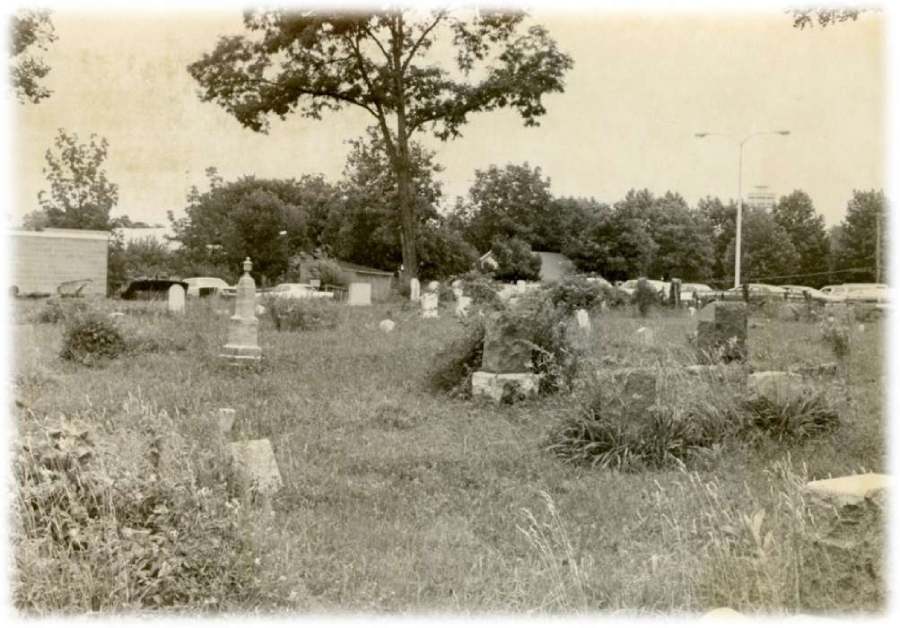

Dalton, who double majored in history and political science, grew up in Gettysburg and would often walk Lincoln Cemetery—established in the late 1860s by the Sons of Goodwill who were leaders in the black community—as a boy. “I found the headstones so fascinating but lamented that there was so little information about the people buried there. Later, I discovered there are actually many individuals who have no headstones or permanent markings at all.”

Now the youngest executive director in Adams County Historical Society’s 80-year history at age 24, Dalton used obituaries, public records, and other resources available through the Historical Society to identify individuals without headstones or permanent markings and expand the information known about those with markers.

He honed many of his research skills, as well as his leadership qualities, at Gettysburg, where he was the president of the College Democrats, leading political organizing, bringing speakers to campus, and managing events. He credits his mentors Michael Birkner, prof. of history, and the late Charles Glatfelter, who was the first executive director of the Historical Society, for inspiring his love of historical research and storytelling.

“Prof. Birkner shares my belief that good history should serve the community in some way,” Dalton said, bemoaning historical scholarship that may only be accessible to experts in journals or esoteric books. “I believe that without that community service, history becomes disconnected from its purpose.”

Having interned with the Historical Society as a teenager (where he met Glatfelter), Dalton has always appreciated the non-profit’s role in trying to ensure the local community has access to its full history. He said, “Unfortunately, black history often gets sidelined or misrepresented.”

Dalton’s growing excel spreadsheet of data was a strong start, but the project was taken to the next level when Gavin Foster, Gettysburg’s associate vice president for information technology, got involved.

“Andrew had done painstaking research and developed a collection of primary sources documenting nearly all the lives of those buried in the Lincoln Cemetery. But it existed only within the walls of the Gettysburg Historical Society on his personal laptop,” Foster explained. “We both agreed it could be a great resource for Gettysburg’s black community and beyond, so I offered to help.”

Dalton was initially hesitant. He worried it wasn’t his place to tell the history of the black community as someone who is not a member of it. However, after consulting with the members of the local black community, including Jane Nutter from the Black History Museum, it became clear that the information would be valuable to local descendants. The community desire for the genealogical information was fully crystalized for Dalton when he was asked by a Historical Society Board Member to research if she had relatives at the cemetery. The findings were emotional. “I was able to tell her that she had a brother who was stillborn and buried at the cemetery. She was in tears. It made me realize that this is information that people should be able to access easily in order to understand and celebrate their ancestors’ legacies.”

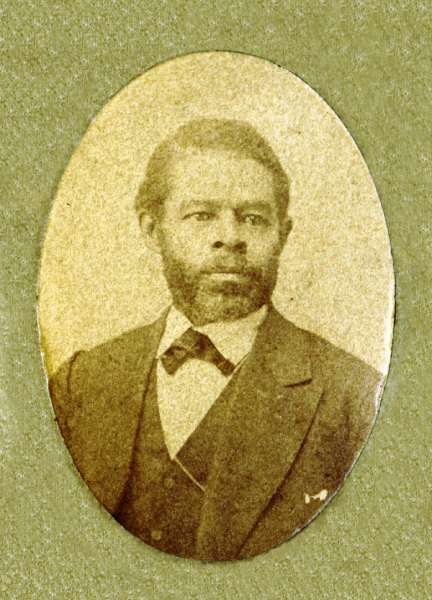

The import of the project is further expressed by Foster. He said, “Put simply, it matters what records are maintained and made easily discoverable. Records of fact, that Basil Biggs owned land or that Mag Palm fought off her would-be kidnappers, are solid and immutable. They are the pre-condition of history. There is a great deal of work to be done in gathering records and making them discoverable if we are to enable more true stories to be told.”

Foster hired Gettysburg students workers to help transform Dalton’s static spreadsheet into a dynamic, digital database that was easily accessible to the public, searchable, and included scans of relevant historical documentation: senior Haider Tariq ’21 (then a sophomore) and alumnus Begench Atayev ’19 (then a senior) who graduated with a BS in mathematical economics.

“Begench and Haider worked tirelessly to design a custom database that would allow for not only people to access the information but also to contribute information and to leave their own memories,” says Dalton.

Tariq is an international student from Islamabad, Pakistan majoring in computer science with minors in data science and business. Since a young teen, he’s been fascinated by technology and software development. When he heard about the digital database project, he was thrilled to be involved in a hands-on application of his passions. What he didn’t expect was how much he’d learn that had nothing to do with technology.

“As an international student, I didn’t know much about the black community outside of the college,” he explained. “I hope people take away from the project a deep appreciation for the impactful role of the black community, both past and present, in the history of a place as special as Gettysburg.”

The digital database is currently available for public viewing and includes information for every person buried at Lincoln Cemetery, including photos of available headstones and historical documentation.

“I’m really proud of the project and the work Haider and Begench completed,” said Dalton. “Gettysburg has so many talented, passionate students who are always ready to dig into projects like this one.”

The Adams County Historical Society is currently in the midst of a capital campaign to build a new facility on the edge of the Gettysburg campus. Dalton hopes it will serve as a research hub for the community and Gettysburg College students. He plans to continue highlighting the hidden histories of the local area. “The building will include a new museum and research center that pays tribute to all of Gettysburg’s stories, not just the battle of Gettysburg, but the entire community history that goes back hundreds of years—from the Native Americans to slavery and all the way through to the Eisenhower era and beyond,” he says. One of the first exhibits planned is called “The Black Voices of Adams County.”

By Katelyn Silva

Photos courtesy of Andrew Dalton ’19, Gavin Foster, and Haider Tariq ’21

Posted: 02/16/21