For drivers, potholes are part of everyday life, but have you ever heard of an electrical pothole? Before thousands of viewers watched a YouTube video from Christina McGahan ’11, they probably hadn’t either.

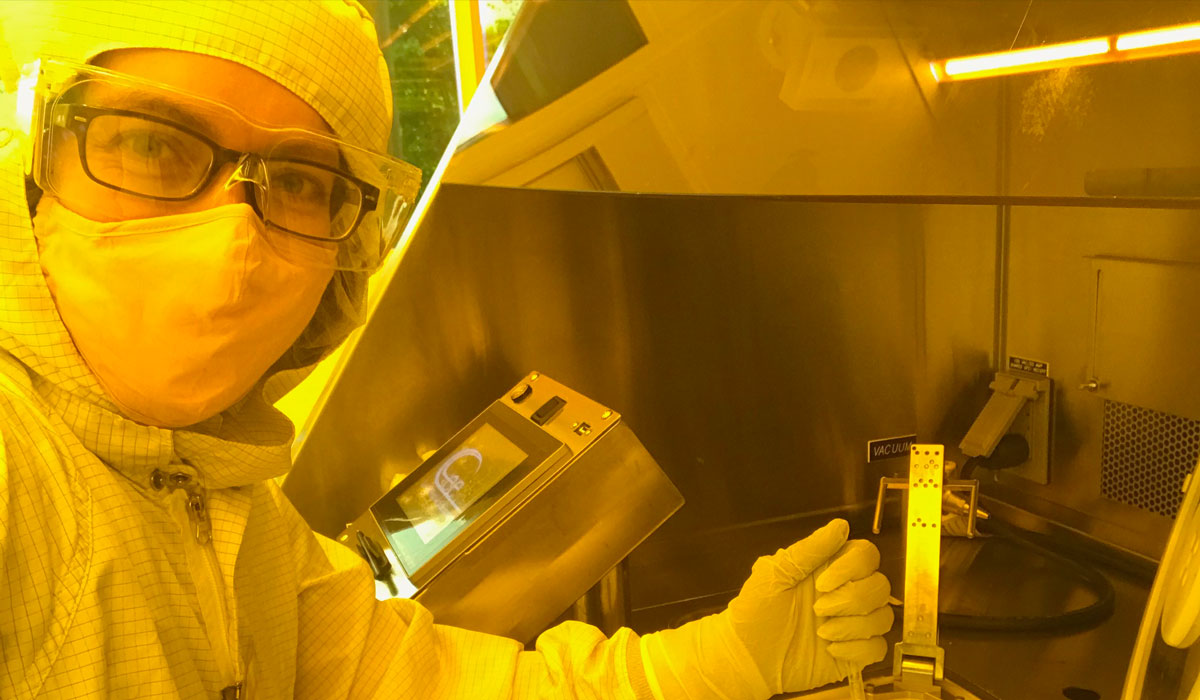

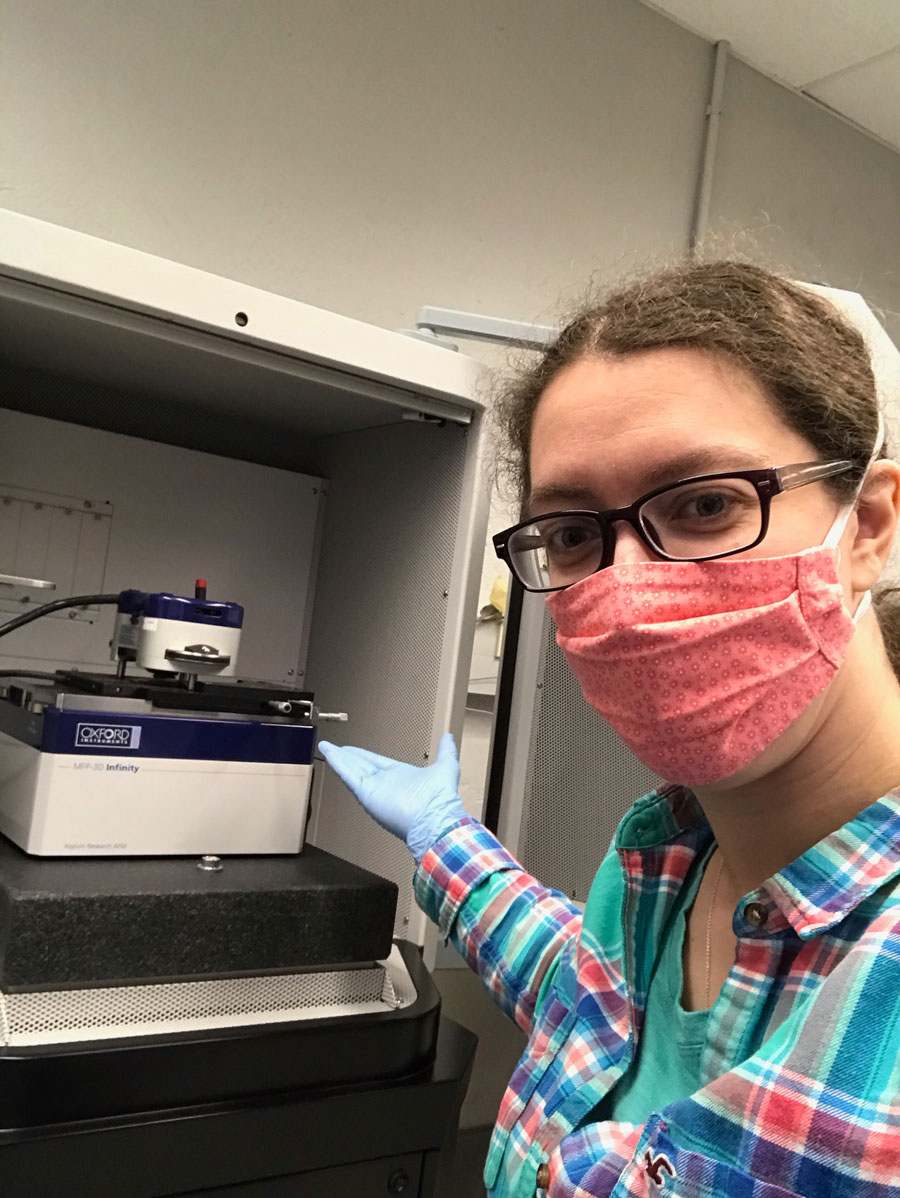

McGahan, who majored in physics at Gettysburg, is an expert on the nanoscale—the really, really small—properties of materials. As a post-doctorate researcher at Mount Holyoke College, McGahan studied the electrical equivalent of potholes, which can slow down the flow of electricity and make devices like phones and computers less efficient. These electrical potholes are so small that a special atomic force microscope that has a tiny finger 1,000 times smaller than the thickness of a strand of hair is needed to find them. McGahan used this microscope to figure out why electrical potholes were forming in materials and how to eliminate them.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, McGahan entered—and won—an online science storytelling competition co-sponsored by the Boston Museum of Science and the National Science Foundation. Her video entry at the 21-minute mark uses props, timing, and a lot of enthusiasm to simplify and explain her research on electrical potholes. The competition was a perfect fit for McGahan who doesn’t just love physics and science, but equally loves helping people understand them, particularly those who might not yet agree on their “awesomeness.” This affinity for science outreach began at Gettysburg College when she volunteered with LEGO Girls, a robotics program that encourages fourth and fifth grade girls to pursue the sciences.

“I think it’s so important to bring the message of STEM to younger individuals or those who may not have had exposure to them,” McGahan said. “Anyone can be a scientist. It’s sad if we lose people who would really enjoy STEM because they're not exposed to it or they’re told—either explicitly or implicitly—that it’s not for them because they don’t see other people like them doing it or just hear very jargony, inaccessible science.”

At Gettysburg, McGahan took part in a number of research opportunities that helped her parse what kind of research she wanted to pursue in the future. In the spring of her sophomore year, she accompanied Physics Prof. Emeritus Laurence Marschall to the National Undergraduate Research Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. At the observatory, the group was able to log data on the brightness and distance of binary stars—two stars orbiting a common center of mass, using a single, large telescopes. She described this “hands-on” experience as “special,” but also a confirmation that observational astronomy was not meant to be her future.

In the following year, McGahon did computational research with former Prof. Michael Strickland, investigating quark-gluon plasma, which are a collection of subatomic particles thought to be part of the “soup” created immediately after the Big Bang. Again, while McGahan found the work interesting, it wasn’t quite what she was looking for.

For her final research experience at Gettysburg, she participated in an undergraduate program at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, where she worked on semiconductors, materials that have an electrical conductivity value between that of a conductor, such as metallic copper, and an insulator, such as glass. She continued that work back on campus with Prof. Timothy Good for her senior thesis and it launched her interest in electricity, which now intersects with her work on nanoscale science for electrical applications.

Today, McGahan is a research assistant professor at Vanderbilt University, where she also received her doctorate. In this new role, she teaches classes, but is also in charge of maintaining the equipment used for nanoscience and providing support to student researchers in the lab. She feels Gettysburg helped lay the foundation for her to be successful at this work.

“It was amazing to be an undergraduate and have a wide breadth of scientific research experiences,” McGahan said. “It helps me even today as I guide undergraduates and graduate students with their own research. It also familiarized me with how to interact and communicate with a wide range of scientists of varying backgrounds and expertise. If I had gone to a more traditional school where you are siloed in your scientific area of study, I don’t think I would have this skillset or be able to communicate scientific concepts to all kinds of audiences as effectively.”

At Gettysburg, McGahan was able to investigate interests beyond science, including a double minor in math and German. One of her favorite classes was “Probability and Statistics” with Prof. Darren Glass, who remembers her fondly as a curious learner.

“Christina had a wide range of interests and clearly embraced the liberal arts tradition, so it was exciting but not at all surprising when I heard she was going to be part of the Boston Museum of Science’s storytelling competition,” Glass said.

McGahan used her storytelling prize money to help with her move to Nashville, Tennessee. At Vanderbilt, she’s looking forward to a long career solving the big mysteries of the very, very small.

By Katelyn Silva

Photos courtesy of Christina McGahan ’11

Posted: 10/28/21