When History Prof Michael J. Birkner ’72, P’10 arrived at Gettysburg College in 1989, he saw the potential to launch an oral history collection, which is now one of the most extensive collections among liberal arts colleges in the nation. Over the past 35 years, it has grown to include more than 1,800 oral histories, each documenting key points throughout history, including the 1960s civil rights revolution. In this reflection, Birkner recounts the 1998 trip he and fellow students and staff took to Lowndes County, Alabama, to collect the stories of civil rights activists as part of this collection.

Visitors to Gettysburg frequently comment on how peaceful the battlefield landscape now appears. The same thing may be said of the sites of another great struggle, the crusade for equal rights for Black Americans in the South. That movement, famously led by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., but made possible only by thousands of foot soldiers, has been much chronicled.

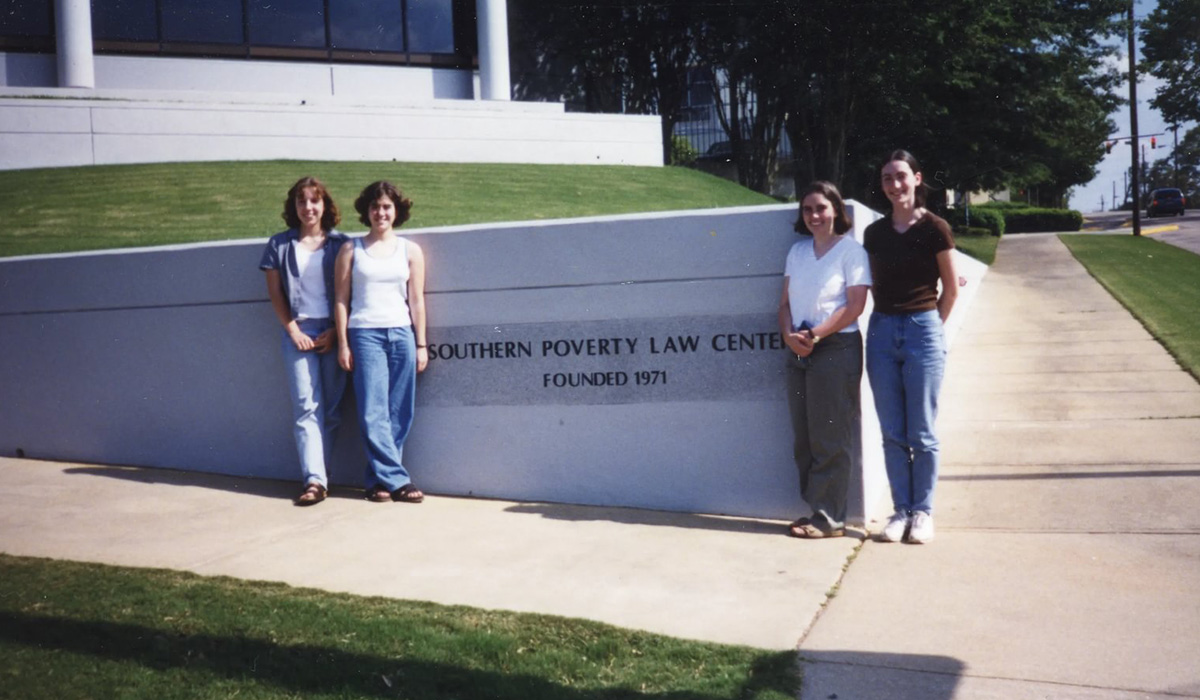

As we approach the 60th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery March—a key marker in the 1960s civil rights revolution—it is worth relating a foray by four Gettysburg College students, Center for Public Service Director Karl Mattson, and me, to collect stories of the struggle for equal rights in “Bloody Lowndes” County in southern Alabama.

This project was spearheaded by Lavinia Rogers ’00 who had participated in a service-learning project in Tuskegee in the winter of 1997-1998. Rogers heard that Bob Mants, a local leader, wanted to collect the stories of Alabama civil rights activists for a museum in Selma he hoped to create. Mants was concerned that time’s passages meant losing voices and failing memories. Rogers, who had completed an oral history in my Historical Methods course, told Mants she would see to it that a project collecting Lowndes County stories would happen. It was Rogers who recruited Mattson, me, and three history students from the class of 2000—Melodie Foster ’00, Amy Lucadamo ’00, and Juniper (“Pepper”) Day ’00, for this purpose.

Having secured the necessary approvals and made the arrangements, following the conclusion of the final exam period in May 1998, the six of us drove to Tuskegee in a College van. We were met by one of Karl Mattson’s contacts, George Paris Jr. From here, our enterprise began to take shape. We were fortunate to have local hosts. Mattson and I stayed at Paris’ home; the students were assigned lodging with a family in town for the duration of their visit.

As we drove through the lush, gently rolling farmland of Lowndes County, I was reminded of comments by American visitors to South Africa in the era of apartheid. As the writer Alan Paton recalled, after lamenting the oppressive nature of the apartheid regime and the seeming impossibility of effecting change in South Africa, visitors would add, “Ah, but your land is beautiful.”

Lowndes County’s landscape is indeed beautiful, but its natural attractiveness cannot disguise the fact that until the mid 1960s it was one of the most repressive places in America. Blacks could not vote, serve on juries, get a decent education or speak freely in the presence of white people. Certainly, they could not openly dissent from what white people expected them to say or do. Lowndes County was a place where whites—a small fraction of the county’s population—had full control of the levers of power and influence. It was a place where whites did not simply threaten those who opposed white supremacy; they did not hesitate to employ violence to maintain the status quo.

How Lowndes County shed white supremacy in an African American-dominated population, and became more democratic, if not necessarily much more prosperous, community is a key story in the civil rights revolution of the 1960s.

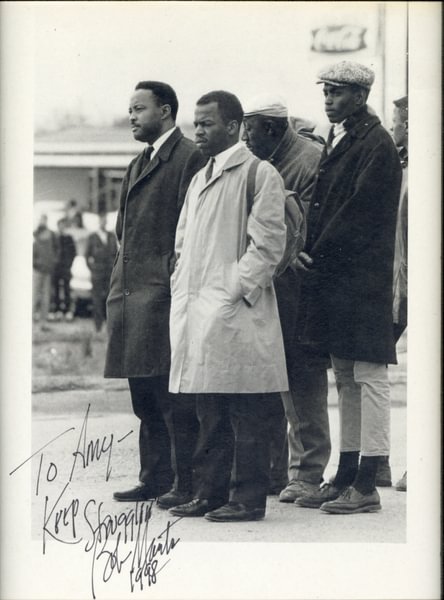

One notable player was Mants, an original SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) organizer back in 1965. Unlike his friend Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), who played an important organizing role in Lowndes County in 1965 and then went on to national fame as the head of an increasingly radicalized Black Power movement, Mants remained in Lowndes County to see the local struggle through. He married and raised a family in Alabama and by the 1990s began lobbying to create a “Freedom Trail” between Selma and Montgomery, to document the civil rights movement in one of its most dangerous and exciting phases.

For the students, Karl Mattson, and me, the experience of interviewing local residents who participated in the struggle for equal rights was profoundly moving. None of the people we talked with were famous. Few were educated beyond high school. Their testimony depended, understandably, on where and when they touched the movement. Lucadamo has recalled that simply being in a place and observing her surroundings made an impact.

“I could see direct connections between history and the present,” Lucadamo said. “This hit me in details like the sprigs of cotton growing wild outside one of our interviewee’s homes or doing an interview at a former Black school that was supposed to be ‘equal’ to the white school nearby but wasn’t.”

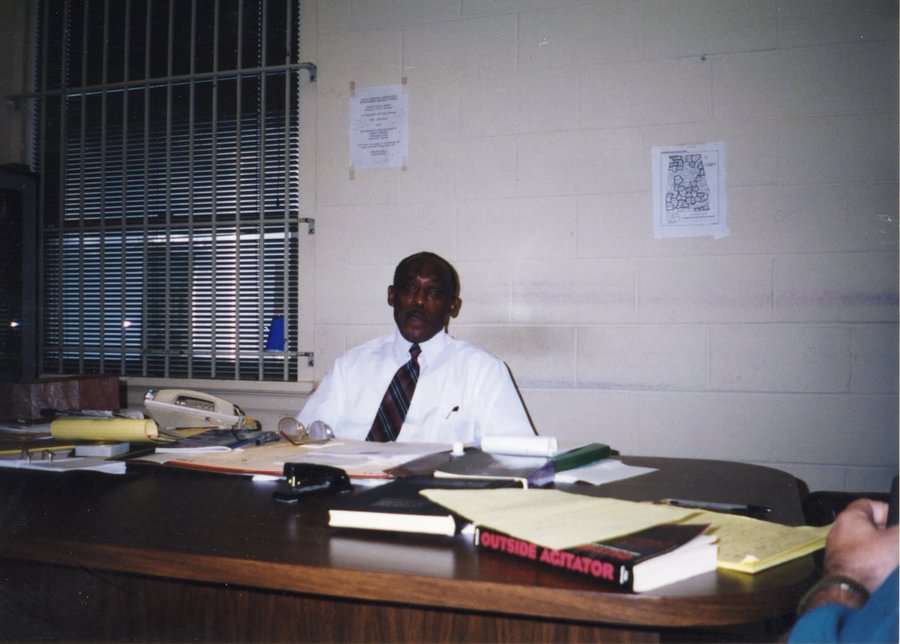

Among our experiences, we interviewed a man who converted his car into a makeshift taxi to transport female domestic workers who were not riding buses to work during the 1955-1956 Montgomery bus boycott; a woman who offered her property as a way station for the marchers on the road to Montgomery in 1965; a preacher who walked with Dr. King; local residents who led voting rights efforts in a jurisdiction that had not validated a single Black voter in the county before 1960; and the man—John Hulett—who shortly after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became the first Black elected sheriff of Lowndes County. We also met an activist who told us to “listen to my story, pay attention to my story,” and proceeded to speak in cadences that amazed and moved us. (Musselman Library Special Collections maintains digital copies of these oral histories, which are the property of the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute in Selma, Alabama.)

What made it possible for humble people to challenge a system of American apartheid, where whites controlled the land, the ballots, and all levers of power in their communities? For some individuals, it was the example of a parent who refused to bend to the system. For others, it was the influence of the church, of a particular preacher or the scriptures. For still others, it was the recognition that if it was not done then, it would not happen.

Everyone who spoke against the system faced danger. Guns were everywhere in Lowndes and contiguous counties. They were brandished openly by whites when in their vehicles and on visits to the homes of Blacks who were causing “trouble.” But for every Black person who flinched, and told the whites what they wanted to hear, others took a stand.

Those who stood up against segregation and discrimination in Lowndes and other Alabama counties were supported by youthful organizers from the North, both Black and white, who helped them develop legal challenges to the system, taught in “Freedom Schools” in the South, and helped to devise organizational strategies. Among those northerners who came to Alabama and elsewhere in 1965 for this purpose were three Gettysburg College students—Richard Hutch ’67, David Hoon ’66, and Scott Chambers ’68. (They drove south that summer with three Dickinson College students.) Hutch had been inspired by College Chaplain John Vannorsdall to pay attention to the unfolding drama over equal rights. He felt that it was the right thing for him to do to heed Rev. King’s call. In an oral history interview more than four decades later, Hutch remembered in detail the texture of his experiences, including one instance where a local white man shot at him.

Hutch was fortunate in escaping with a scratch. Others were not so lucky. One of the “outside agitators,” as they were known in the Deep South, was Jonathan Daniels, an Episcopal seminarian from Keene, New Hampshire. Like Hutch and others who came south in 1965, Daniels was animated by stories of barbaric treatment of Blacks in Alabama and motivated by Martin Luther King’s call for clergy to march from Selma to Montgomery. In 1965, Daniels traveled south to work in the voter registration drives then in progress. He arrived fatefully in Lowndes County.

Daniels was briefly jailed in the county seat of Hayneville in August 1965 after participating in a protest in nearby Fort Deposit. He was released on bond and told by the local sheriff to “get the hell off county property.” Soon thereafter, he and several compatriots, including a Catholic seminarian named Richard Morrisroe, walked a few hundred feet from the town green to buy Cokes at a small cash store.

As Daniels opened the screen door, a white man named Tom Coleman, carrying a shotgun, ordered Daniels and his friends to “get off this property, or I’ll blow your goddamn heads off, you sons of bitches.”

Daniels turned to respond, whereupon he was met with shotgun fire that tore a hole in his chest and killed him almost instantly. In the pandemonium that ensued, Morrisroe was also shot, but not seriously wounded. Coleman was indicted for manslaughter but was quickly acquitted by an all-white jury.

While our Gettysburg cohort was based in Lowndes County, we interviewed people who remembered Jon Daniels’s murder in cold blood. One of our interview subjects, Esther Jordan, sobbed as she recalled how the whites of Hayneville “just let Jon Daniels’ blood run cold in the street; they wouldn’t touch him, wouldn’t lift him.” Others recalled that Daniels’ death energized members of the Black community and reminded them not to let up in efforts to pursue fundamental change.

We were moved by this vivid testimony. We were touched to see a monument to Daniels’ life that had recently been erected on the corner of the town green. The county had refused to allow a monument to be placed at the site of Daniels’s murder near the general store. (By the time of our visit in 1998, the store was gone, replaced by an insurance agency.)

The week we spent in Alabama was transformative for us. However, we were regularly reminded that while outsiders like the young idealists of the 1960s played a part, along with brilliant leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, it was local people and their determination that provided the essential fuel for the civil rights movement.

Esther Jordan sang an anthem she remembered singing in 1964: “Ain’t nobody gonna turn us ’round.’” No one would turn her around, not even when shot at, at close range, by a lackey of the local plantation owner who happened to be her father-in-law. That resolve was contagious in Lowndes County.

Lowndes County today is a very different place from what it was in 1965, in terms of the rights of citizens regardless of color. That said, it remains an open question whether the “arc of justice” Dr. King referred to is still bending towards freedom.

By Michael J. Birkner ’72, P’10, Professor of History

Photos courtesy of Amy Lucadamo ’00, College Archivist

Posted: 03/27/25