When people think of dynastic marriages, they probably think of unions forged from political necessity rather than love or affection. They may think of cold, distant, and even loveless relationships.

According to history Prof. Magdalena Sánchez, that isn’t always true.

She’s spent the past several years reading and analyzing the sixteenth-century letters between Catalina Micaela, Duchess of Savoy, and her husband, Carlo Emanuele I. Born in 1567, Catalina was the daughter of Philip II of Spain and Elisabeth of Valois, but she left Spain to marry Carlo in 1585, and bore him ten children before dying in 1597.

Portrait of Carlo Emanuele I of Savoy, by Jan Kraeck (known as Giovanni Caracca), Saluzzo, Museo Civico Casa Cavassa.

Carlo Emanuele saw his marriage to Catalina as a means to an end—he had ambitions towards securing and expanding the borders of Savoy, which had only recently regained crucial territories from France, and a marriage with the daughter of the strongest king in Europe might bring him great prestige as well as military assistance against France. Carlo also knew that Spain might welcome this alliance because of Savoy’s strategic location close to France and on the Spanish military supply road which extended from northern Italy to Flanders. What evolved from that marriage was a relationship that not only defied modern notions of arranged marriages, but also forces us to rethink the role of women at early modern courts.

“It was a partnership that worked for political and economic reasons, but there was also clearly a lot of love and affection, too,” explained Sánchez.

Finding an academic path

Sánchez first dove into early modern Spanish history when looking into graduate school programs. Having received an undergraduate degree in history from Seton Hall University, she knew she wanted to continue studying history, and gravitated toward areas that would take advantage of her fluency in the Spanish language.

The early modern period seemed a natural fit.

“I’m always drawn to a person as a focal point of research,” said Sánchez. “The personalities of the early modern world are what make it such an interesting time period.”

After receiving a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, she explored her interest in historic personalities throughout her professional career. In particular, her past research has focused on women who, through piety and family relations, played prominent roles at the Spanish court.

It’s also how she stumbled on the largely forgotten letters between Catalina Micaela and her husband.

“I was interested in her older sister, Isabel, and went to Turin, Italy, to look for letters she wrote to Catalina. While I never found them, what I did find was this amazing correspondence between Catalina and her husband,” Sánchez explained. “I made the decision—almost right away—to change direction and focus on the correspondence of two figures who are largely unknown in the Anglo world.”

“It was one of the best decisions of my professional career,” said Sánchez. “I look forward every day to my work because I like my research now more than ever before.”

Sánchez has received prestigious grants from the Renaissance Society of America, the Spanish Ministry of Culture, and Gettysburg College to continue her archival research in Italy and Spain during the 2016-17 academic year when she is on sabbatical.

Challenging contemporary norms

What makes these letters so unique are the minutiae shared in them.

“The letters are filled with details that I think historians look for but often don’t find,” Sánchez said.

The letters cover a range of topics, too, contradicting many stereotypes of women in early modern history.

Portrait of Catalina Micaela de Austria, Duchess of Savoy, by Alonso Sánchez Coello, 1584-85, oil on canvas. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

The first—that women were submissive and had little political influence. As Carlo Emanuele pursued military campaigns on the borders of his territories, he left his wife in charge of the duchy, serving as his lieutenant.

“It’s clear that she was responsible for negotiating for him,” Sánchez said. “She was taking care of daily elements of governing, acting as a diplomat and negotiator and even as his purveyor—sending him munitions and medical supplies when he needed them.”

Mixed in with political and military discussions are updates on the health of their many children, remarks on daily activities and tidbits of gossip, references to their pets, and comments about gifts they sent to each other regularly.

What stands out the most to Sánchez are how deeply personal these letters are, contradicting the second stereotype of aristocratic women in this time period—that their marriages, often arranged and for political or economic gain, were devoid of love and affection.

“She often writes about how much she misses him and sometimes tells him that she has put his letter under her head while she sleeps,” Sánchez explained. “The letters are treated as material objects of affection—gifts, even—to the point that she even sleeps with the letters in his absence.”

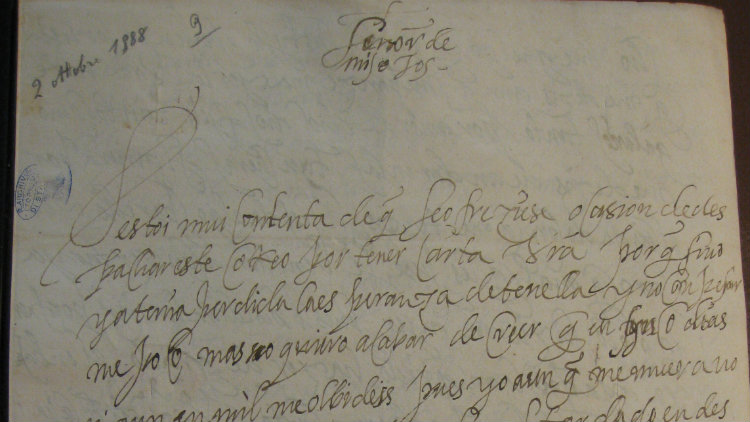

One of the letters written from Catalina Micaela to her husband, Carlo Emanuele. Archivio di Stato Torino, Corte, Lettere Principi Savoia, Duchi e Soverani, mazzo 35, fascicle 1, folio 9r.

Advancing scholarly research

One thing that Sánchez said transcends the sixteenth century is the way couples communicate during periods of separation—from sharing gifts and portraits to conveying their feelings of loneliness without the other.

The only difference is how those sentiments were expressed.

“There’s an art to the way they wrote,” Sánchez said. “Every single letter starts with a salutation, ‘Lord of my soul’ or ‘Lord of my heart,’ and he returns it, ‘Lady of my soul’ or ‘Lady of my life.’ There is an art or a grace in how they express themselves. Now, we make a phone call or we email or text. We don’t write many letters, and so we’ve lost that culture of letter writing.”

Sánchez is offering a senior seminar in the fall of 2017 that will explore these and other letter writing practices in greater depth. In the meantime, she is turning her research on Catalina Micaela and her husband into a book while also publishing scholarly articles and giving public presentations on the topic.

“Catalina Micaela is a fascinating, very dynamic woman who wielded a significant amount of power, but she is also a relatively unknown figure from this time period,” Sánchez explained. “I’m hoping to introduce her to a larger audience, and also to have that larger audience see that a negotiated marriage could develop into a marriage of affection and even love.”