In Episode 17, President Bob Iuliano is joined by two members of the Gettysburg College community: Psychology Prof. Sahana Mukherjee and Gretchen Natter P’15, assistant dean of College Life and executive director of the Center for Public Service. They discuss the impact of gratitude on our health, the variability in how people express gratitude, and how we at Gettysburg College foster a culture that recognizes the significance of giving back to the community and working toward the greater good.

Listen now on SoundCloud

Show notes

In Episode 17, President Bob Iuliano is joined by two members of the Gettysburg College community: Psychology Prof. Sahana Mukherjee and Gretchen Natter P’15, assistant dean of College Life and executive director of the Center for Public Service. Together, they discuss the impact of gratitude on our health, the variability in how people express gratitude, and how we at Gettysburg College foster a culture that recognizes the significance of giving back to the community and working toward the greater good.

The episode begins with Mukherjee unpacking what role gratitude plays in our lives and how it affects our emotional and physical wellbeing. In doing so, she references psychological research which has shown that those with a stronger orientation toward gratitude tend to report higher life satisfaction and greater levels of optimism, among various other health benefits. Later on in the episode, Mukherjee explains how expressions of gratitude can vary across cultures.

Continuing the conversation, Natter connects these concepts of gratitude that Mukherjee shared to the Gettysburg College community. She puts into words the short-term and long-term goals of the College’s Center for Public Service and how students, faculty, and staff engage with the Center in pursuit of community change—from helping with soup kitchens and english as a second language classes, to participating in immersion projects across the world.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has made hands-on giving a challenge, Natter and Mukherjee share some creative ways in which individuals can give thanks and give back this holiday season. Natter suggests identifying an area of immediate need that means something to you and to your loved ones, and contacting those agencies to see if they have ways to engage virtually, or have immediate needs for donations. Mukherjee encourages mindfulness—remembering to see the good in our lives and going out of our way to say “Thank you.”

The episode concludes with an anecdotal “Slice of Life” told from the president’s perspective. Iuliano uses this moment to reflect on what he’s grateful for this holiday season. He’s grateful not only for what our students, faculty, and staff bring to the Gettysburg College community but also for his membership in such a resilient and good-willed community.

Guests featured in this episode

- Sahana Mukherjee, associate professor of psychology at Gettysburg College, whose research interests lie in topics of social justice, with a specific focus on the role of cultural tools in the reproduction of privilege and disadvantage.

- Gretchen Natter P’15, assistant dean of College Life and executive director of the Center for Public Service at Gettysburg College.

Transcript

Gretchen Natter: I think one thing that’s been exciting to me to watch is our students, whether they’re on campus or they’re studying remotely, they’re still getting together and exploring what it means to be community organizers in a crisis.

President Bob Iuliano: Hi, and welcome to Conversations Beneath the Cupola, a Gettysburg College podcast. I’m Bob Iuliano, president of the College and your host. At Gettysburg College, giving and giving thanks is more than a holiday tradition. It’s an orientation that our students, faculty, alumni, and broader community carry forward throughout the year.

President Bob Iuliano: In this episode, we’ll look more closely at the concepts of gratitude and giving at the college and beyond. Guiding us through this conversation will be to members of the Gettysburg College community, Sahana Mukherjee and Gretchen Natter. Sahana is a psychology professor whose research interests lie in the topics of social justice with a specific focus on the role of cultural tools and the reproduction of privilege and disadvantage. Gretchen serves a dual role at the College as the Assistant Dean of College Life and as the Executive Director of the Center for Public Service. Together, we’ll discuss the impact of gratitude on our health, the variability in how people express gratitude across cultures, and how we at Gettysburg College foster in our students the mindset of helping others and the instinct to work toward the greater good.

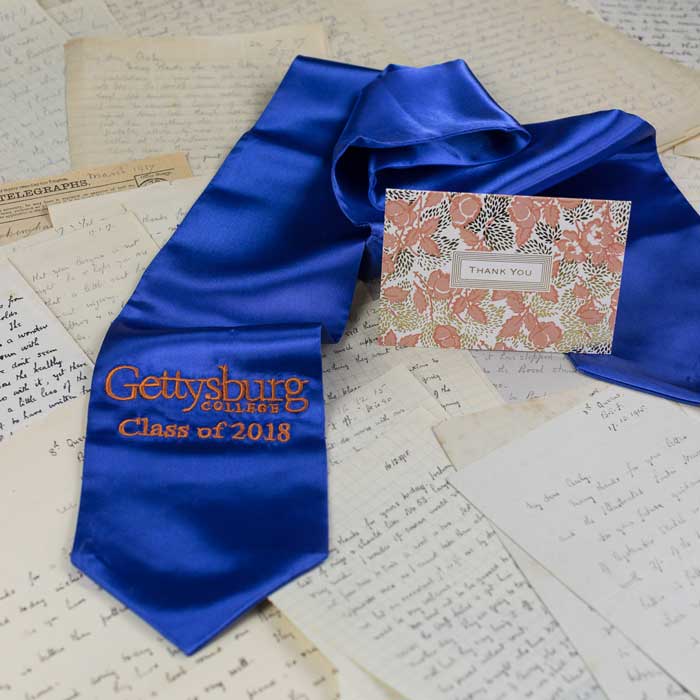

President Bob Iuliano: Sahana and Gretchen, thank you so much for joining us today. Really looking forward to this topical conversation about gratitude as we head into Thanksgiving. It’s obviously something that matters here at the College. And we have manifested that in a variety of ways, probably most visibly through our tradition of the stole of gratitude, where graduating students give stoles to one or more members of the community faculty, support staff, administrators, who really helped them during their journey here. But I want to go beyond the sort of narrow personal, as important as that is, and maybe start a little bit with the science behind it, Sahana, and perhaps start with you. How does gratitude influence ... What role does it play in our lives and how does it affect our emotional, physical wellbeing, our way of looking at the world?

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: Thank you, Bob, for having us. So over the past two decades, researchers have found that in a way, how you know that gratitude is positively associated with overall wellbeing, specifically, it’s been linked to lower levels of depression, anxiety. Those who have a higher orientation towards gratitude also tend to report higher life satisfaction, greater levels of optimism, and they also report having better sleep and also sleep longer. It has also been linked to experiencing less burnout, and in general, being less reactive to stressful situations.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: While some of this research is correlational in nature, meaning that we can’t say for sure gratitude is what causes people to sleep better and longer. There have been some recent efforts to determine causational links. So for instance, researchers have used experimental designs where they have randomly assigned people to groups, where one group gets to keep a gratitude journal where they write, say, five things that they’re grateful for, for a period of say eight to 10 weeks, while another group doesn’t really do that. And what researchers found, that people who kept this journal for a long period, so eight to 10 weeks, reported more positive moods and overall life satisfaction.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: What was really fascinating was that this even extended to health outcomes. So a pilot study that was published a couple of years ago showed that heart failure patients who kept this gratitude journal for eight weeks, compared to those who didn’t, experienced more gratitude, which in turn showed reduced signs of heart inflammation and improved blood vessel functioning. And researchers believe that this is happening because what gratitude is doing is that it’s counteracting hedonic adaptation. This is basically when we tend to acclimatize to positive developments in our lives. We don’t enjoy them as much because we kind of don’t see them anymore and we take them for granted. And what gratitude does is make these everyday positive developments more visible, and so we experience it again and then it results in these physical and mental health outcomes that I’ve noted.

President Bob Iuliano: That’s fascinating. It also suggests that the relationship between mindfulness, or sort of pausing and reflecting, matters as much in the state of gratitude, because it’s a willingness to reflect on it and to be aware of it, and that influences the sense of gratitude itself.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: Yes, absolutely. Because it’s a very deliberate form of reflection, and that’s connected to mindfulness as well.

President Bob Iuliano: So we’ve used gratitude so far in ways that I think I understand, but I would imagine that there are people who give gratitude and people who receive it. How do we think about that? Those experiences different for the recipient versus the giver?

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So it’s different in the sense like what we’re measuring. So so far the research that has looked at, say, physical health outcomes have mostly focused on the givers of gratitude. However, there is research suggesting that when we receive gratitude, it also makes that receipient feel very, very deeply appreciated. And actually researchers suggest that it works like a social glue. It inspires people, the givers and the recipients, to be more generous kind and helpful. It strengthens relationships, including romantic relationships, and it can also improve the workplace climate.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So for instance, research found that when you receive an expression of gratitude, it motivates us to affiliate with that same person, the giver of gratitude, in the future and reinforcing our social bonds. It also motivates us to be more comfortable in voicing relationship concerns, which can then in turn strengthen relationship satisfaction. And more broadly, it actually makes us more willing to help others. So not just help the person who expressed the gratitude to us, but help others in general.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: And a cool study actually found that experiencing gratitude can actually improve productivity. So a field experiment found that fundraisers who received an expression of gratitude from the supervisor increased the number of donor solicitation calls they made, because it increased people’s feelings of social worth.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: And then the last thing I actually want to say about this is that clearly there’s a lot of evidence saying that when someone expresses gratitude to us, we feel good and we do all these great things. But the fascinating thing here to note is that a lot of times where we, like say if I want to express gratitude to someone, we may hesitate to do so because we tend to underestimate how good that recipient is going to feel and we overestimate how awkward they will feel. And recently some colleagues of mine actually did some cool studies that demonstrated that people when they were asked to write gratitude letters, and asked to report, “Okay, how awkward do you think this person is going to feel when they receive that letter?“ really overestimated that. But the recipients didn’t feel awkward at all and they actually felt great. So the next time we think, “That person’s going to feel a little awkward, should I send that thank you card?” Don’t, because you’re likely overestimating that.

President Bob Iuliano: That’s a great piece of advice. Gretchen, you’re in the business of helping our students make a difference in ways that matter to people. And that strikes me as a form of an expression of gratitude. It’s more than that, but let’s back up a little bit. You have your dual roles, but focusing now as your responsibilities over the Center for Public Service, just some people may not know exactly what CPS does. Say a word or two about it.

Gretchen Natter: Sure, sure. So ultimately, our goal is to understand with the students the complex work of community change, and how they particularly and specifically can engage in it, connecting their personal work to the work of others, addressing those larger community change issues and in the longterm, bringing up that systemic change. And so yes, that means that we’re doing the immediate needs or the direct action kind of work. So children are being tutored, they’re working in soup kitchens, they’re working with English as a second language programs with adults throughout the community, but then we also do the work to make sure that they see how their personal involvement is connected to issues like community-generated research questions. What are we learning through this work together that informs what further work needs to be done? Through those relationships that they build, they’re having dialogue with people that experience life in a different way. And so then how do we gain a more complex picture of what’s going on in our world?

Gretchen Natter: They’re also exposed to how coalitions work to support families and individuals and address those changes. It’s not just discrete to groups of people, but we find that community power through organizing together and better able to tackle issues. And all of that is informed by education. Not just educating perhaps the client in a program, but educating the broader community about how issues of hunger, of immigration, of poverty eradication, of immigration are affecting our particular community. Kind of breaking down those national statistics into a local context.

Gretchen Natter: And finally, we want them thinking about policy too. Not just state, federal government policy, but also how institutions from everyone from the college, to school systems, to local nonprofit organizations, and even businesses are making decisions that affect our local community and the folks living here.

President Bob Iuliano: In a given year, roughly how many students are doing something through CPS?

Gretchen Natter: Yeah. So in a normal year we see more like 1,500 students who are involved in Center for Public Service programs. And we see that about 90% of those involved are involved in at least 10 hours over the course of a semester. So some of those are doing more, some of those are doing less, but most of our programs are really focused on that sustained involvement, focused on that relationship building.

President Bob Iuliano: In the pandemic I imagine this has all become more complicated to do since we have fewer students on campus. And it’s probably more complicated to get even those students on campus out into the community. So how have you navigated that?

Gretchen Natter: Yeah. So a couple of ways I think that we’re really proud of. One is that our campus community farm, which serves as a hub for food justice has continued to operate. And that’s so important because 29 immigrant families have plots there. And so while we can’t have hundreds of people gather there the way we have in the past, there can be groups of 10 people, masks, following protocols, and so families can still tend their plots and have access to culturally appropriate and healthy foods. And at the same time, we’ve been able to support shares in the farm with over 20 people, getting weekly bags of fresh produce that helps fund then the workshops, the supplies, all those kinds of things for the families involved at the farm.

Gretchen Natter: Our students have continued to run that space, working shifts, doing the weeding, doing the harvesting. And we have been able to make sure that they are sometimes with the families so that they can share in those stories and for that love of food and being together. And that’s a really powerful space.

President Bob Iuliano: What motivates people, these 1,500 students to want to participate in CPS programs? And what do they get out of it personally at the end of this work and this exploration that they’re undertaking?

Gretchen Natter: I have a story to tell about that that kind of illustrates this idea. So last year, we were beginning a new program with the Gettysburg Black History Museum to mentor young African-American and Black youth in our community. And after the first session, we were driving back to campus and I was in the car with the executive director or the president of the board for the Black History Museum, and with two students. And these students they represented different regions of the nation, different viewpoints. And we get a quick drive through Gettysburg to show them some of the history that related to their heritages, and their family histories. And pointed out places of stories that aren’t often told. And on the way back, they’re like, “Ms. Jane, Gretchen, this has been so powerful because for the first time I see myself represented in Adams County, in the town of Gettysburg.”

Gretchen Natter: And then what we saw after that is because they had this sense of place here, then they were able to build strong relationships with the kids and to keep in touch with them and to relate on that community focused level. And now for some people, it takes a while of building the relationships, say with the families at the farm, or the adults that they work with through ESL classes, that then they begin again to see what their place is here. They feel a connection while the community members might express gratitude towards our students for investing their time, whether it’s in their education or in their wellbeing, our students much more vociferously, much more strongly will talk about the gratitude that they feel for the Gettysburg community, and helping them find a sense of place and a sense of belonging here.

President Bob Iuliano: Boy, doesn’t that just reinforce the point Sahana made earlier, that there is a bilateral relationship here. You didn’t quite say it in that way, but that there’s glue that forms from these interactions that take place.

President Bob Iuliano: Sahana, back to you for a moment. Do environmental conditions affect the likelihood of expressions of gratitude? That is, and this may just be purely an individualistic thing, but are you more likely to find expressions of gratitude in times of stress or in times of plenty?

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So far there hasn’t been much report on those kinds of environmental conditions, mostly because expressions of gratitude can vary. So it can be verbal, nonverbal, it can also vary in gift-giving versus an action. But there is more evidence talking about environment in the sense of culture. So there’s cultural context play a role in how one expresses gratitude.

President Bob Iuliano: So what are some of the differences in the way gratitude is expressed across cultures?

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So researchers, and this is something that’s been done very recently, because much of the research initially just focused in the U.S., And specifically amongst white Americans. But more recently scholars looked at children across various countries, as well as within the US across various ethnicities. And what they found was that people who live in contexts where there’s a greater emphasis on relatedness rather than the sense of individualism, or a greater emphasis on hierarchy, rather than the sense of autonomy. In those contexts, people are more likely to express what we call a connective form of gratitude, where there is a sense of reciprocity, but it’s less transactional, and it’s less about saying, “Whenever you need something, let me know,” because to the extent that persons of a higher status, well that doesn’t seem quite appropriate to save.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So this is something that you would see in the Chinese context and the South Korean context, and research has found even amongst the Iranian and Malaysian context, people were less likely to say things like, “Thank you, let me know if you need anything.” And they were more likely to think of expressing gratitude in more nonverbal ways or actions that are not directly reflecting that specific thing that they are grateful for.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: And in contrast to that, you have children in the more North American context. So U.S. and Canada, Western European context, where there’s a greater emphasis on autonomy. And there’s a greater emphasis on individualism. And in those spaces there was a greater expression of verbal forms of gratitude. So saying thank you, and additionally saying things like, “Well, let me know when you need something,” because it’s seen in a more egalitarian lens. And also what researchers call concrete gratitude, where there’s a specific farm of gift giving pretty soon after you want to be thankful for.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: And this goes back to kind of a developmental origin. So for example, I think about the elementary school classrooms in the U.S., Where it’s not uncommon for kids to spend time creating gifts for their loved ones. And more often than not, the kids reflect what they think the loved ones want, but more often than not, it’s reflecting their favorite color and their favorite TV show. And that’s something that you see a lot amongst adults as well. So those are some of the variations folks have found.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: Within the U.S., Researchers looked at how European Americans in general expressed more verbal gratitude than Latin Americans, and Asian Americans in the US expressed the least. But that doesn’t mean that they experienced the least amount of gratitude. So it’s mostly about expressing it differently, not so much about experiencing it differently.

President Bob Iuliano: Interesting. I do wonder that as culture gets shaped by changes in technology and particularly social media and the means in which we interact, whether that too will have an influence both in the frequency and means of expressions of gratitude across cultures. I don’t know if that’s been studied, but I can imagine it would be an interesting place to dive in.

President Bob Iuliano: So we are also existing in a moment, not just a technological change, but also in a moment of a pandemic that has made interactions harder and has put more stress on systems and the like. Yet we are still seeing, Gretchen, people doing a lot to get engaged, to find means of expressing gratitude. As you think about this, particularly through the prism of CPS and our College, how can our students, how can our faculty find outlets for them to get engaged, to help give back, to find their own expressions of gratitude?

Gretchen Natter: Yeah. That’s an excellent question, and one we’ve received a lot, especially since March. Ways that we’ve been advising folks is, one, to identify an area of immediate need that means something to you and to your loved ones, and contact those agencies to see if they have ways to engage virtually, or if they have immediate needs for donations. We’re seeing so many of our agencies and community initiatives who are losing funding. So that kind of monetary and material support is heavily needed. If you’re not quite sure where to find those things, you can call 2-1-1, which is a way for folks to access services, but it’s also a way for folks to access volunteer services as well. So no matter where you are, that’s the place to look.

Gretchen Natter: I would say though, at the same time while you’re thinking about those immediate needs, is to think critically about why those needs they exist. What in our social systems of support are failing that are causing people to access those emergency services, and not just on a one-time basis, but to go back to that over and over again. And so how can we be a part of solutions about long-term change?

Gretchen Natter: I think one thing that’s been exciting to me to watch is our students, whether they’re on campus or they’re setting remotely, they’re still getting together and exploring what it means to be community organizers in a crisis. And it’s been so gratifying to watch them rise to that challenge. So working with partners and youth serving organizations, and creating a remote tutoring option that now is going three nights a week and engaging kids in grades K through six from the El Centro program. But again, that was student led, student designed, with some guidance, but really their energy made that happen. And they got in their partnership, they got in their thinking about what needs are, responding to family requests and those kinds of things

President Bob Iuliano: Sounds phenomenal. Last set of questions. And that is, gatitude matters. Sahana has underscored that it helps us emotionally, psychologically, and physically. We’ve talked about the stoles of gratitude as being something that is embedded in our campus. Sahana, you commented that people still need to learn though about both how to express it, how to receive it to some extent. What can we do as a college to make expressions of gratitude and experiences of gratitude become more readily available to all members of the community, perhaps especially in this moment of time where people are feeling a bit more worn down by the realities imposed by the pandemic?

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: You’re so right Bob, in that the cause of the pandemic in many ways, we’re cut off from so many social interactions and you’ve actually notes some of challenges, and what the pandemic is really doing is that what things are mundane, it’s become even more mundane. Because we’re cut off from so many social interactions, all of those novel experiences that we might be used to are no longer there. So we’re seeing the same people for the same part, we’re eating the same food for the most part. And not to say there’s nothing good in our homes or in our workplaces, but at a certain point because of that whole hedonic adaptation tendency that we have, we really stopped seeing that good, and it becomes invisible.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: So really the goal is to make the everyday more meaningful and more visible. And while of course, the stoles of gratitude do that once every four years, and it’s a beautiful, meaningful tradition to really institutionalize that sense of gratitude amongst everyone and build that sense of community, what we can do on an everyday basis is also equally important.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: I know there are some structures in place as well on campus that really, again, institutionalize this idea of gratitude. So for instance, we have the Pillars of Appreciation program, which while it’s used every year to support and recognize employees all over campus and express gratitude, this might be the year where we might especially be motivated perhaps to fill in and recognize more people who have helped us. Whether it’s working on a printer because the paper just did not come out, and somebody just spent a few minutes on that or helping with Zoom, I think from the college community perspective, it’s about recognizing those everyday actions that at first seemed really, really mundane, but highlighting it, and again, as I noted earlier, expressing it. And not feeling that, “Oh that person is going to get all awkward about it,” but really expressing it, whether it’s in the form of an email or more formally through the Pillars of Appreciation program that already exists in Gettysburg College.

President Bob Iuliano: Gretchen, any thoughts on your end?

Gretchen Natter: Yeah. As I think about this, in addition to these institutional ways that you’ve described so beautifully Sahana, I think about the little ways that we build it in over time, that then end in celebration. We learned from one of our partners at the Circles of Support, of starting every gathering, whether that’s on Zoom or whether that’s someday again in person, with going around the room and everyone sharing something that’s new and good. And so it’s not necessarily always expressing gratitude to other people in the room, but it’s a naming of something that’s going on. And sometimes that’s community related, sometimes that’s something really personal. Sometimes it is the gratitude for another person in the room. And then when we see those kinds of things building, those conversations happening, those moments of vulnerability with each other, sometimes that then that can lead to celebrations together.

Gretchen Natter: So for example, in Nicaragua, when we are able to have an immersion project there, or summer fellowship, our hosts always have a despedida for the students who are there. And a despedida is very culturally based. And so there’s food, there’s dancing, there’s music, there’s laughter, there’s storytelling, but always part of it is this very joyful moment where host mothers and fathers get up with their new host Gettysburg College children, and very publicly declare their gratitude, what they have appreciated about those students. And then in turn, our students share their gratitude back. And often then that moment is ... There’s also an exchange of some kind of physical expression. So a little gift of remembrance and those kinds of things. And that’s really beautiful because it’s so public and it’s so embedded in how people celebrate being together. And so I think both of those building in and the every day gatherings, as well as these intentional public celebrations of how we impact each other can be really powerful.

President Bob Iuliano: Well, let me publicly declare my gratitude to both of you, with no sense of awkwardness whatsoever I hope, Sahana, for the really wonderful conversation we just had, and that I hope will cause people to reflect on the things that they’re thankful for and make them more willing to express that sense of gratitude to others. And I know that this community is fortunate to have both of you as part of it. So thank you for this conversation, and enjoy the upcoming holidays.

Gretchen Natter: Great. Thank you, Bob.

Prof. Sahana Mukherjee: Thank you, Bob.

President Bob Iuliano: Let me conclude with a slice of life from Gettysburg College. This podcast’s focus on gratitude offers me the opportunity to reflect on the profound appreciation I have for the many people who have helped the College navigate what has been a six months unlike any other in recent times. It’s been a moment of adaptation and change, calling on resiliency and good will. We’ve seen that reflected in our faculty, who continue to respond to changing circumstances with an inspiring commitment to our students and their educational progress. We’ve seen it in our administrative and support staff, who have had the responsibility of remaking a campus in response to the pandemic. And perhaps most of all, we’ve seen it in our students, who have had their collegiate experience disrupted, and have continued to find ways to find meaning and connection.

President Bob Iuliano: In the spirit of this season, I’m grateful not only for what our students, faculty, and staff bring to this community, but I’m also grateful to be part of this community. To be able to work with and live alongside the people who live the values of this campus everyday. Let me end this slice of life by asking, what are you grateful for? Leave us a comment. Thank you, and enjoy the upcoming Thanksgiving.

President Bob Iuliano: Thanks for listening. If you’ve enjoyed this conversation and want to be notified of future episodes, please subscribe to Conversations Beneath the Cupola by visiting gettysburg.edu, or wherever You get your podcasts. If you have a topic or suggestion for a future podcast, please email news@gettysburg.edu. Thank you, and until next time.